by Beth Everest

by Beth Everest

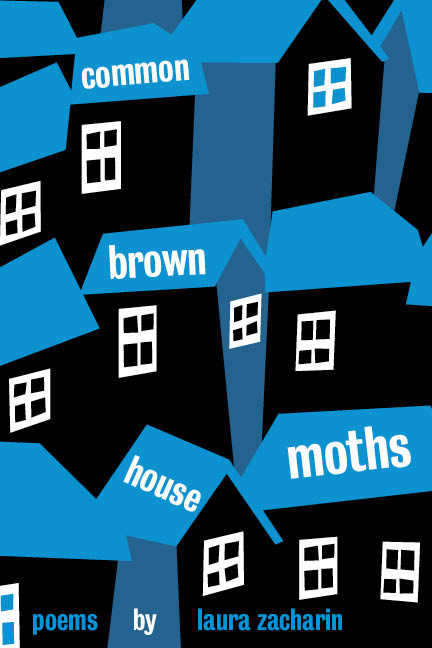

Common Brown House Moths

by Laura Zacharin

Frontenac House (2019)

ISBN: 9781927823989

Common Brown House Moths by Laura Zacharin is anything but common. Already the first line, of the first poem, tantalizes my senses. The poet’s word choice and use of image are stellar. “Amygdala” is compared to “golf ball innards;” and then, the evocative “loop after loop of rubber strand stretched” (7) becomes the interconnected imagery of loss and memory and grief and sorrow that link one poem to the next and the next. Take the final image of the first poem, for example: “newspapers flapping in a tree” is not only a strong visual in its own right, but it serves as metaphor for small glimpses in different lives, and links to the second poem with “glancing up from his paper, spread out / when she tried to explain how nerve fibres/branch” (8). We find echoes of the newspaper, plus other kinds of papers, such as in “Shadow Twin” (35), we have the character complement to Rosie; and in “A Beginner’s Guide To”:

It isn’t really mine, it’s just

a noise that skitters through me,

the weather, buzz of traffic,

an occasional loon on a lucky summer night

but mostly, other people’s conversations,

wrappers, empty bags and jars

and scraps they’re done with (67)

The it (and the variety of paper in the poems) not only creates the image but reminds us of the poem that is a shared happening before and after it is in a written form. This is what I so like about Zacharin’s collection, the seamless gathering of leaves / edges / branches of images lighting other images, in poem after poem, or paper, or like a moth after another moth.

And there it is, the title image: common brown house moths. The title doesn’t simply refer to a single bothersome housemoth or two buzzing lazily, but a scourge in the kitchen and all over the house:

Exhumed moths and moth parts. Under the rug.

In the coats. Inside shoes, ball caps. Desiccated shreds.

…tangles of webwingbodylegs. (8)

Notice the poet’s evocative word use with exhumed and desiccated and the squash of webwingbodylegs. The scourge becomes a problem, at first for the mother referred to in the poem, then later for the speaker of some of the other poems, but clearly the moths become metaphoric for so much more as we move through the collection. It’s cleverly done.

Even so, the words introduce a death, of sorts, or at least a developing change in the amygdala, that “pair of shriveled almonds between a rock and a hard / place” to which we were introduced in the first lines of the poems. They work as a satisfying set of images.

The interlapping, as we might call it, of imagery continues, and the primary images of paper and moths develop throughout the poems as we witness the mother’s progressing illness. Watch how this works:

Now, she starts losing weight, “could hardly breathe,” forgets, loses words:

The aaahs, and uhhhs, a kitestring in the Boxwood, newspages strangled

the Summersweet. She smacks her lips. And besides

they say poetry of witness is dead. They the new poetry

is poetry of absence. Just forget it. Just I said anythi (11).

Not only do we see this absence/illness in the absence of letters on the page, but many of the poem titles are suggestive of the change in the mother: “Same Same and Different” (12), “That Summer Between Everything” (16), “Watches the Mouth for the Shape of the T”(18), “When the Weather Turned.” These pieces resonate gripping truth, “like in that dream loop when you can’t get to the other side” (16), or moths that won’t go away, or lice “the whole scalp dizzy // with bugs. Leggy and frenetic, bellies taught with blood” (41),

But the messages keep coming,

Like sideways rain or darkness or drunkenness orLike someone’s trying to tell me something

I should know by now. (13)

For the persona, the messages become the moth scourge. And the mother loses so much weight, she becomes moth-like, and more like paper, as we see in the “tissue paper flaps, barely tethered at her back” (36). It is implicit that we could even refer to the mother as the moth(er), “Light/ like a shadow. Like she was by then” (37).

Where does all the flesh go

when she slowly disappears

like that. (65)

Where does all the flesh go? It is a good question; and in this question the poet asks not only of the corporeal self, but of the mother who returns in flashes of the old self, in flashes of the before:

She squints back to a time

when she was kind

long ago, before she was or

before she became or before she

before she felt the, before

… (48)

Notice the change in poetic form as the mother moves from the before to the later stages of the Alzheimer’s:

She grew fangs a curve

in her spine, her nails curled

to claws. In a burgundy housecoat (53).

It is the scourge of the disease.

There isn’t only one mood in Common Brown House Moths. Changes are shown in content, image and rhythm, but also by layout of text on the page. The poet slides adeptly between the more conventional freeform poem, to the looser broken line that begs to be read aloud, to block-text such as in the evocative “In the Light Of “(22), to a sense of urgency created by the use “Watches the Mouth for the Shape of the T” (18)

The variety in form works both visually and for sound/breath pauses. The interrelated images hold the book tight in this beautiful collection. I enjoyed the double meaning created in the line breaks, and the lighting in and out of the serious subject matter. The moths and their referents are gorgeous.

Perhaps the poem that moved me even moreso than many of the others was “Before I Leave, I Wrap You in Red” and especially the final stanza:

I hear it. The ice breaking, at the lake, the low pitch wail beneath.

It’s like someone crying at the bottom. But no one’s crying

And this time, I’m not too late. I hear

The broken floes and deep below, their sorrow song. (44)

Beth Everest recently retired from 30 years of teaching, and hopes against hope for more time to write and make jewelry. Her most recent book, silent sister: the mastectomy poems was shortlisted for numerous awards and went on to win the BPAA Robert Kroetsch award.