by Jamal Ali

by Jamal Ali

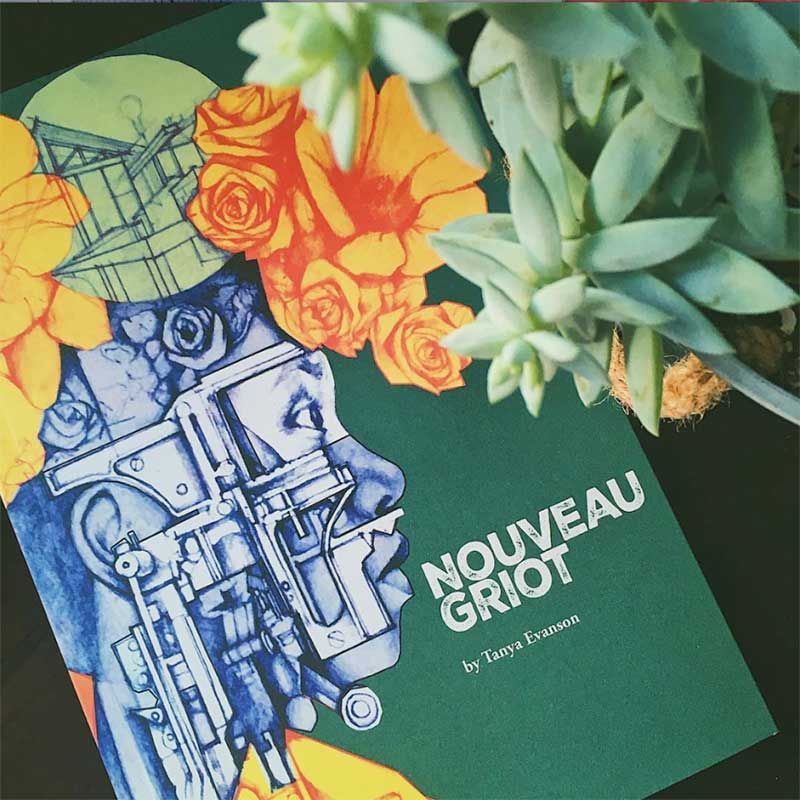

Nouveau Griot

by Tanya Evanson

Frontenac House (2018)

ISBN: 978-1-927823-84-2

Tanya Evanson’s poetry collection, Nouveau Griot, takes readers on a journey into diverse worlds. A griot is a french African word meaning “travelling poet, singer, storyteller, or musician […] to whom supernatural powers are often attributed.”

The poet’s journey with others through the Bolivian Amazon aboard a dugout canoe on the Yacuma River is the subject of “The Invisible World.” The following lines from the second stanza rich in metaphor stun the imagination: “The water, / a pure milk coffee, swallowed us into foam. I placed the lips of my / fingers and the piranha snapped from the river’s glass ceiling, sharp / marine mouths into hand, catfish, minuscule shark. The sky, a woven / cloud. Roots, the scalps of slain indigenous, molten into the fibre, / broken unlike elastic” (12). I revel in Evanson’s praise for the wildlife: “From the canoe, I threw my skin to bless trains of turtles, high red / monkeys, giant white-combed manguari, massive open- mouthed caiman / crocs” (12). A beautiful moment revealed by the poet and captured on camera is powerful: “Back at the village, we slept for long hours in Amazon sun in a courtyard / full of mango, avocado and monkey. A bliss so throwing it put the / invisible world into view for a fortunate flash” (13).

“Bangkok Business,” portrays the hustle and bustle of Bangkok: “Hell is business in fine clothing though people are good to me and / national-blue orchids grow by the side of expressways, we flourish in the / beauty methane. Heat. Motorcycles and surgical masks on all the / downtown faces. Tuk tuk taxis. I catch my first elephant in Bangkok / traffic” (15). A feeling of unease surrounded me while reading the following: “Cars know no / lanes. Motorcycles, no boundaries. No safety but from air” (15).

“Almost Forgot My Bones,” is referred to by the poet as A Song for East Vancouver. Evanson’s power of motion in a new city is evident: “I was living in a sketched coastal town / Autumn water pouring down like my new motion / It took a while to groove, near this new ocean / But my new motion moves” (18). The fifth and tenth stanzas (a repetition) suggests that in order to find herself the poet must travel past skin and into bone:

Try, because I almost forgot my bones

In this home without no mirrors

Almost forgot my bones

In this home without no mirrors

Of myself, my skin, my kin, my hidden. (18, 19)

The narrator’s experience with discrimination inspires resilience and reflection on white colonial history:

Just then I thought, who are these new folks

Reminding me that I am black?

Who are these folks? Is this a Vancouver fact?

Or had I forgotten this historyStraight from an 1858 act of black foot

Up from San Fran, stepping onto British Columbian land

Already meant for indigenous holy hand and spirit

We all colonizers, we all colonized. (18)

Evanson’s transition from a feeling of loss and fragmentation to acceptance of the community around her is remarkable: “Now when I search for community, / Not only through skin unity do I find love / I find love from above, from below / From four corners of streets / I find movement with beats / We each use to complement each other / And implement change” (19).

In “Devil’s Bridge” and “Antigua, Antigua,” the poet’s employment of colourful Caribbean Creolized English adds flavour to the poems. It conveys the authenticity of the Caribbean environment and experience.

The depiction of the collision of two bodies of water on opposite sides of a Caribbean island in “Devil’s Bridge” is fascinating: “At northeastern tip, pon deh island of Antigua in West Indies, is a / remote area known as Indian Town. Wild. Island edge. Atlantic Ocean / pon one side, Caribbean Sea pon odah. Crash into each odah. Deep / ragin swells. No end. Since time” (52). The explanation for the creation of a natural arch known as Devil’s Bridge captivates me: “At dis place deh is a natural rock bridge. It come straight outta seawater. / Erosion. Geological ocean. An ark. A rock. Bridge carved by deh sea / from deh saf n deh hard. Limestone ledge. Action breakers. Atlantic / waves rollin ovah centuries a wav com faaaaar, from Africa.” (52) Sadness engulfed me when I learned about the fate of black slaves at Devil’s Bridge: “At dis / place intellectual slaves committed mass suicide” (A lot of slaves from the neighbouring estates use to go there and throw themselves overboard rather than submit to slavery) (52).

“Antigua, Antigua,” is a testament to Evanson’s yearning for her homeland:

Me las an found / Me feel profound

Attachment to Antigua, AntiguaYes me wan dat tide / In dem roots me hide

Me heritage an me pride / Antigua, AntiguaFar from muddahland tight clothes no sweat / Not like Canada

Cold cold cold cold cold cold FIYAH! / Antigua, AntiguaMe nah Gretzky / Me nah sorry / Me nah tank ye / Me nah foo’

Antigua, Antigua. (53)

Nouveau Griot is an interesting read. This poetry collection is a must for readers eager to experience various settings.

Jamal Ali lives and writes in Calgary. Originally from the Caribbean island of Trinidad and Tobago, Jamal immigrated to Canada together with his parents and siblings in 1967.