by Tia Christoffersen

by Tia Christoffersen

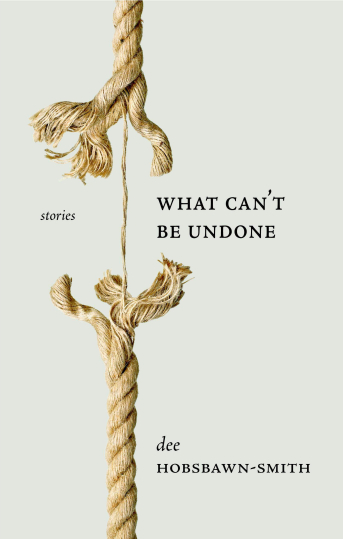

What Can’t Be Undone

by dee Hobsbawn-Smith

Thistledown Press (2015)

ISBN 978-1-927068-89-2

From the award-winning culinary writer and poet dee Hobsbawn Smith comes her first collection of short stories, What Can’t Be Undone. She tells fascinating stories of human connection and passion in the midst of loss and tragedy. With captivating and sometimes haunting imagery, Hobsbawn-Smith cultivates images of the Albertan landscapes that house her troubled and honest characters.

Hobsbawn-Smith’s thirteen stories do not idealize the characters, but instead offer realistic and human depictions of people coping with adversity. While reading the collection, I felt both sympathy for and disappointment in the characters, as if they had come to life and I knew them personally. Each story poignantly explores its characters’ flaws, desire, and pain.

A chef loses her senses of smell and taste, threatening her livelihood and her passion. Years after her brother’s death, a woman grapples with feelings of responsibility and guilt. A retired bull rider confronts his own complicity in his brother’s spousal abuse. While each character and their circumstances are drastically different, they share the common thread of facing what seems impossible. Every reader will have experienced this at some point in their lives, which is what makes Hobsbawn-Smith’s stories so relatable.

In the story “Monroe’s Mandolin,” a bar owner tries to help her twin brother, struggling with addiction, and longs for her late mother, a musician. Driven by nostalgia and hope, “Monroe’s Mandolin” follows the protagonist as she tracks down her mother’s mandolin: “Mom had the thing restrung for her southpaw hands and she played it for years. It sounds undamaged by its travels, and when I run my fingers down the strings, their vibration amplifies the tunes trapped in my throat like asthma” (12).

Striking imagery runs through the entire collection, appealing to all the senses. The story “Exercise Girls” is exemplary of such imagery: “All I could smell were the possibilities of spring in the Fraser Valley, wet alfalfa’s green funk, musky sedge leaking into early bloom, the old-socks rankness of cattails” (146). With her naturalistic descriptions, Hobsbawn-Smith makes the reader feel as connected to the stories’ settings as her characters do.

Hobsbawn-Smith’s stories display her extraordinary ability to take an abstract concept and mould it into a tangible object. “The Quinzhee” demonstrates her skill at articulating what seems indescribable: “They say that when disaster strikes, time slows and stretches, turns to pulled taffy, and that you can see through its membranes to the other side” (71).

Captured in the collection is the human reaction to associate tragedy with a place or object. In “The Pickup Man,” this notion is investigated after a woman’s husband is convicted of domestic violence: “Their house has too much of her blood in the floorboards for her to ever want to see it again” (85).

Because Hobsbawn-Smith explores more sensitive themes in her collection, it should be cautioned that some may find its in- depth exploration of the events a bit troubling. Intertwined with enthralling images of Alberta scenery is an examination of what compels us after experiencing loss and tragedy.

Tia Christoffersen is obtaining her Bachelor of Arts in English (Honours) at Mount Royal University and co-hosts a comedy podcast in her free time. She writes fiction, plays, and a lot of to-do lists. She is a frequent contributor to FreeFall Magazine.