Annie Vigna

Annie Vigna

a review of

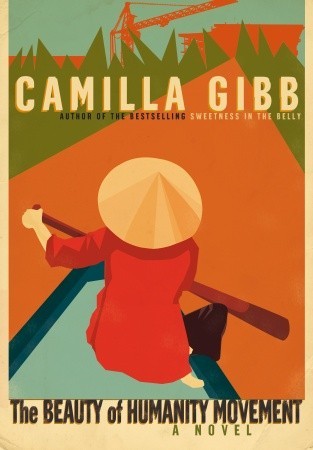

The Beauty of Humanity Movement

By Camilla Gibb

Doubleday Canada

ISBN: 978-0-385-66322-9

$32.95

Hu’ng’s neighbours have begun to line up with their bowls. The old man has special power—he is the heart of this place, was the heart of the Beauty of Humanity Movement—he brings people together, keeps them fed (223).

Camilla Gibb has chosen this fictional character, an ageing Hu’ng, to tell the story of about seventy years of life in Vietnam, particularly Hanoi, seventy years of turbulent history–political unheavals and customs of the Vietnamese. From the 1930s through colonization by the French, occupation by the Japanese, communism, the American War (Vietnam War) and economic liberalization, otherwise known as Doi Moi, the story evolves through five characters Chien, Hu’ng, Dao, Binh, and Tu–each representing a successive generation faced with its specific tensions.

The ninth of ten children, born with a large dark mark on his face, Hu’ng is sent from home in 1933 by an unloving mother to live with his Uncle Chien in Hanoi. Chien teaches the boy all the intricacies of preparing pho, the aromatic noodle soup enjoyed by Vietnamese for breakfast. Following Chien’s demise, Hu’ng inherits the pho restaurant which could be compared to the French cafes that once also attracted the creative minds who met there—writers, poets, and artists–intellectuals whose work was considered critical of the government. And because this group, The Beauty of Humanity Movement, was deemed to be critical of the government, it was shut down, forcing Hu’ng to relocate his cart-driven pho kitchen almost daily; but his loyal customers, bowls and chopsticks in hand, find him. As the following scene unfolds, Hu’ng “has set up shop in the empty kidney of a future swimming pool attached to a hotel under construction near the Ngu Ha Temple”

Hu’ng recognizes each man by the state of his hands: the grease moons under the nails that mark a mechanic, the calluses of one who works a lathe, the chewed nails of a student writing exams.

But then whose lovely hands are these amidst this parade of manly paws? The delicate hands of a woman

who has, improbably, never engaged in manual labour. And the bowl. Shining, Translucent. Porcelain. ….You’ve come to me for breakfast before?

No, she says, revealing herself a foreigner with just one word.

Maybe I knew you when you were a child?

I don’t think it’s possible, sir. I grew up in the U.S. But perhaps you knew my father—Ly Van Hai.(9)

So, on page nine, the novel’s second raisonneur is introduced in the person of Maggie, art curator, born in Vietnam, but who was forced to flee with her mother to the United States some twenty years previously.

Maggie moves the narrative along because of her desperate insistence on finding information about her beloved father. Hu’ng is forced to delve into his faded memories to cogitate past experiences and, in doing so, weaves together the various strands of each of the five generations, skillfully connecting these characters through their basic humanity. Gibb uses Tu as Maggie’s guide to illustrate the modern Vietnam, vibrant and bustling. Tu is ambitious and modern. Even so, he sees Hu’ng as his grandfather and fully expects that the woman he would marry should respect and love Hu’ng as much as he does.

Gibb’s anthropological background and thorough research are what inform the reader; her gentle treatment of the universally recognizable human traits of the characters is never compromised because of age, privilege, war or peace.

Camilla Gibb’s other published works are Mouthing the Words; The Petty Details of So-and-so’s Life; and Sweetness in the Belly.

This review appears in FreeFall Volume XXI Number 2 Fall 2011.