Micheline Maylor

Micheline Maylor

A review of

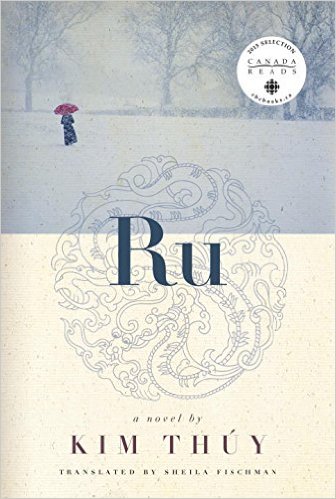

Ru

by Kim Thúy translated by Sheila Fishman

Random House Canada

ISBN 978-0-307-35970-4

$25.00

Refreshing and devastating, Kim Thúy’s (pronounced two-ee) Ru is translated superbly to English by Sheila Fischman. Ru previously won the Governor General’s award in French in 2010. It is the story (fiction/memoir hybrid) of Nguyen An Tinh and her family’s journey from war torn Vietnam in 1968 while fleeing the communists. It is a tale woven in vignettes. Each vignette is artful in its prose. Thúy shows moments, or develops character precisely. These vignettes then tumble towards a full story in an effective accumulation of impressions.

Thúy manages a deft and powerful telling of her migration, and immigration with poetic skill, potent imagery, and engaging narrative. With sensitivity Thúy recreates a number of experiences. In this passage about her journey as a “boat person”, she pinpoints her child point of view: “[F]ear was transformed into a hundred-faced monster who sawed off our legs and kept us from feeling the stiffness in our immobilized muscles.” (5). Ever increasing stakes for the narrator and her family are related in such a way that I read the entire collection wide-eyed. The tension did not relent even as the family immigrates to Quebec.

Thúy also manages metaphor with complexity. Memes seamlessly entwine: money, corruption, class, motherhood, mental illness, illusion, home, love, life, similarity, dreams, cycles of life, hopelessness, woundedness, heroes, knowledge, dislocation, and desire. Metaphor is handled poetically and creates a layering effect in the storytelling. Just one reading of this book impossible, and improbable. The author’s subtle handling of so many issues is pleasing and crafty. I re-read the book through seven times over the course of a few days and continued to extract new ways of seeing the subject(s), scenes, and characters. Every reading was equally wide-eyed for me. Perhaps this had to do with the complete absence of sentimentality and nostalgia, and Thúy’s adept use of language. In addition, her narrative point of view takes on a childlike quality, as though other realities, beyond the one told, do not exist, a trait the narrator inherits from her father.

As for my father, he didn’t have to reinvent

himself. He is someone who lives in the

moment, with no affection for the past. He savours

every instant of the present as if it were the best

and only time, with no comparisons, no measurements.

That is why he always inspired the greatest, most

wonderful happiness, whether holding a mop on the

steps of a hotel or sitting in a limousine en route to a

strategic meeting with his minister (64).

The present encompasses each narrative in Ru until the totality of the collection forms an overall dominant impression and it feels like something profound has happened, something refreshing and devastating.

In a CBC on-line interview with Thúy, she reveals the structure of Ru was not intentional. She merely, “picked up where she left off the day before,” nor is she comfortable calling it a novel or even a book. She claims, “my job was to remove the unnecessary words.” What she leaves is the essential moments that build to a full and impacting picture. Consider this partial passage, just one of Thúy’s many character portrayals:

I thought he was mute. If I ran into him

today, I would say that he’s autistic. One day his foot

slipped on the morning dew. And bang, he was

spread out on his back. BANG! He cried out

“BANG!” several times, then burst out laughing.

I knelt down to help him get up. He leaned against

me, holding my arms, but didn’t get up. He was

crying. He kept crying and crying, then stopped

suddenly, and turned my face towards the sky.

He asked me what colour I saw. Blue. Then he

raised his thumb and pointed his index finger towards

my temple, asking me again if the sky was still blue (85).

Ru allows us to consider these simple questions on the crest of subliminal and political complexities without direct questions. Thúy challenges us to different ways of seeing. The craft of the lines and words becomes spellbinding, just the way a good piece of narrative should. This book is highly recommended.

This review first appeared in FreeFall Volume XXII Number 3.