Micheline Maylor

Micheline Maylor

A review of

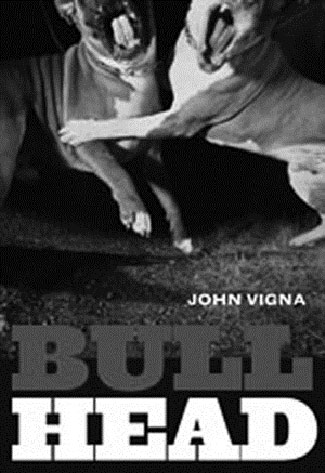

Bull Head

by John Vigna

Arsenal Pulp Press (2012)

ISBN: 978-1-55152-490-0

$15.95

The epigraph to John Vigna’s debut short story collection begins with Flannery O’Connor’s words, “. . . the man in the violent situation reveals those qualities least dispensable in his personality . . .” This is no epigraph. It is a warning, sure as the surgeon general’s on the cigarette pack.

With deft handling of character, imagery, and language, Vigna draws us to the men of logging country, B.C., their foibles, their weaknesses, their flaws, their inept dealings with love. The characters in the book reek of dysfunction. Each main character is unable to process or comprehend the situations they find themselves in.

Vigna’s portrayals are unflinching and real. While it would be easy to turn away, Vigna manages to compel and attract the reader with energetic prose and satisfactory development ~ enough to sate morbid curiosity. I am reminded of the words of Nietzsche, “and when you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” These characters are full of emptiness, undefined longing, and strife. Vigna handles the question: what does a man do when he can’t make sense of his world? In “South Country,” Billy takes action.

I grabbed the scythe, clutched it tight. Hops had his back to me, his jeans were at his knees, and his belt flipped back and forth against the dirt. I raised the scythe above Hops; the girl’s eyes widened. The quad wailed closer, Harley’s voice screeched in the air. I wanted to tell her that it’s okay; it will all be okay, that it will pass and you’ll be fine. It might take some time, but you’ll learn to slash it out of you bit by bit, leave it behind until maybe there’s nothing left. Nothing left to do but survive (144).

Vigna’s ambiguous scene causes dry-mouth and heart palpitations. I read these stories wide-eyed.

Vigna’s ability to tell these hard stories, so effectively, is fascinating and a study in line-level craft. The prose takes processing time as each sentence is choreographed precisely. I had to walk away from the story to allow the imagery and desolation of the character’s circumstances and choices to settle before I could move to the next. Each man says something about the difficulty of expressing love, and the violence that comes because of it: Earl and his sex-shop blow up doll; Sonny and his dog called Bacon Face; Brian and his fighting dogs; even Maurice and his love for a lame horse lead to a violent but telling climax when it is time to put her down.

“I never miss. You should know that by now.”

Harold nodded, his head heavy in the crosshairs. Maurice steadied his finger on the trigger, wiped his eye against his shoulder, and restrained the rifle.

His first shot shattered the windshield; the sound tore open the morning. The second shot blew a hole in the grill. He reloaded and emptied again into the body of the truck, shooting and re-loading and shooting from different angles (84).

Vigna is an exceptional builder of suspense. He does not shy away from the darkness in characters, nor does he pull back. With an unflinching eye, he builds scene, dilemma, and character. There is no mistake that this collection has garnered much praise and attention, including nominations for the Danuta Gleed literary award, Salty Ink’s most dazzling debut, Steven Beattie’s book of the year list 2012. Vigna’s prose is unforgettable. But fairly warned, this is not a book for sissies.

This review appears in FreeFall Volume XXIII Number 3.