Annie Vigna

Annie Vigna

A review of

A Root Beer Season

By Inge Bremer-Trueman

Crabapple Mews Collective

ISBN 978-0-9920795-2-9

$17.95

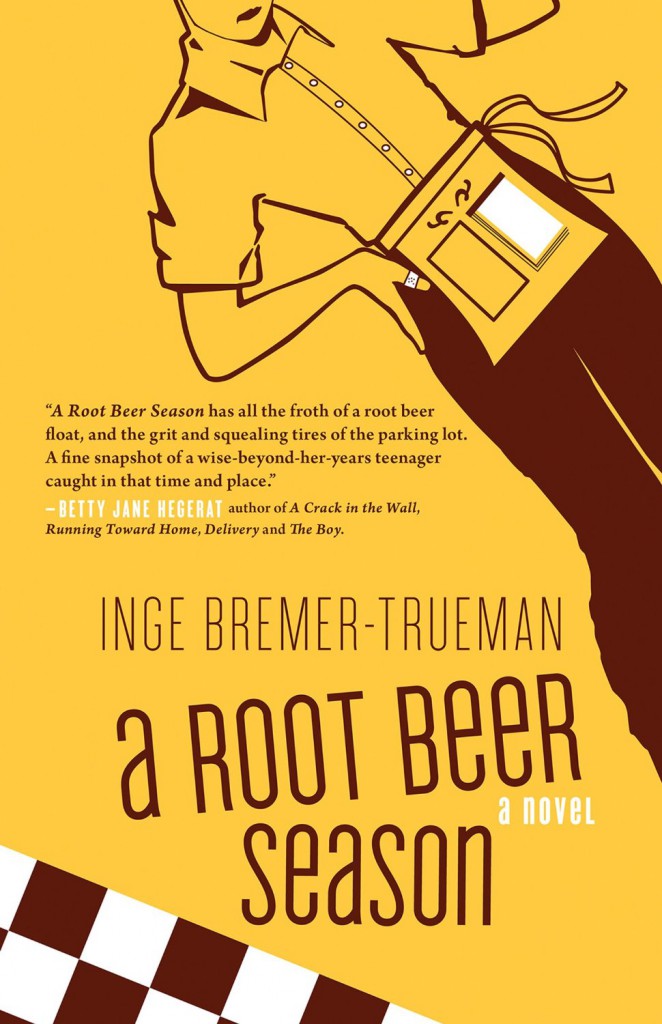

The cover shows a teenage girl dressed in an A&W carhop uniform, complete with apron and order pad, a jaunty pose with hand on hip exposing a band aid on her thumb, the other arm mostly out of sight, elevated, and presumably holding a tray; regulation brown pants completing the figure. And at the bottom of the page continuing across the spine and onto the back cover, a section of checkered racetrack insignia with a shiny new car completing the picture. Congratulations to Natalie Olsen, of Kisscut Design, for the evocative design of the cover and the front endpaper of A Root Beer Season. It is a perfect introduction to this first novel by Inge Bremer-Trueman, hereafter referred to as “Trueman”.

Sparkling dialogue written in the authentic voice of a fifteen-year old narrator Sonja Pfeiffer is what carries this novel set in Edmonton in the summer of 1967. Sonja is a typical teenager of any year, hormones budding, but still under control, desirous of being independent of scrutiny by her parents, who in her case, were born in war-torn Germany, clinging to a strict, unforgiving religion, Gemeine Alles Gottes (GAG) that restricts almost every enjoyment. While her father deviates from time to time, listening to Patsy Cline on the Motorola, and insistent on having a television, her mother nags her and her two sisters, Hanna, two years older, and Nadia, two years younger, into submission; but, they find ways to freedom. Only the eldest sister Brigitte acquiesces. In contrast to this strict Christian dogma is the new age wisdom of Edgar Cayce. When mother discovers his book hidden in Sonja’s bedroom, she considers it tantamount to the worst kind of treachery, akin to treason.

Such familial tensions are inescapable, and Trueman unflinchingly creates the perfect ambience necessary to tell her story, along with language and vernacular totally suitable to the story. Sonja, like her older sister Hanna, works as a carhop at the local A&W, shops at Woodward’s or Eaton’s, and dreams about being with Bernie, with arms wrapped around his waist, as he careens down the street on his brand new Yamaha motorbike. Sonja is crushing on Bernie because of his brand new Yamaha motorbike. She is saving up to buy a motorbike of her own. But Alexander in his spiffy red Camaro comes along and Bernie is easily forgotten. Speedy vehicles excite Sonja, but not half as much as the guys who drive them.

While Sonja longs for a motorbike or a shiny red Camaro, her best friend and confidante Audrey longs for love, hopefully with Woodward’s bag boy Seamus; instead, she falls for a 23-year old blond teacher of her younger brother Clarence. “We did it, you know”(204). The repartee between these two girlfriends is hypnotizing. Audrey, wrapped up in dreamy afterglow, expounds on the beauty and sexiness of Nicholas Palacios, while Sonja tries desperately to imagine “what ‘doing it’ was like” (205). Then Audrey disappears. Later that summer Audrey writes Sonja a letter, with no return address, telling her “she’d gone to Saskatoon to stay with her Aunt Rosemary”; a second letter “said she wouldn’t be returning to school”. Sonja’s naïve response, “Holy! I thought. Her auntie must be at death’s door” (215) speaks volumes of both hers and Audrey’s innocence.

With astonishing skill, usually attributed to veteran storytellers, Trueman allows the reader to compare and contrast this love story to that of Sonja’s own parents during WWII in Dresden that resulted in the birth of older sister Brigitte. Her mother’s confession in nine pages serves two purposes: One, as an expository of Hitler’s dominance over the lives of Germans and, more particularly, over the lives of a soldier and his girl during desperate circumstances and, two; to warn her daughters of the dangers of promiscuity in 1967 in a free country. Somehow, the telling, the confession, the flawed mother, was heart-warming to Sonja.

Regardless of what events of her parents’ past drove them to Canada, they clung to their roots, to memories of their youth, and longed to legitimize their past. Trueman dramatizes this in a rather tender communication with her mother, as follows:

“You know,” I remember her saying once as I sat at the kitchen table, doing homework while she made supper, “Before the war, when Germany was still one land, Dresden was a wunderbar city of much culture. Like Paris and London, it was. They call it the Florence of the Elbe. You Kinder learn nothing of culture. I know you have never even heard of Goethe.”

“I have so heard of him,” I said. “And Freud, too.”

“He didn’t come out of Dresden, Goethe did not, but he was a very famous German. He was a Frankfurter”. I didn’t want to push her reminiscence button just then because, I remember, My Favorite Martian was about to start and I needed to get my math finished. I looked up at her. “You mean he was a wiener?”

You are funny girl she said. “If he was Wiener he would have come out of Vienna.”

She didn’t laugh very often, but her chuckling that afternoon sounded like it was coming right out of her soul and I promised myself that from that time on, I would try to make her laugh like that every day (154-155).

This novel of 335 pages is never boring. It depicts “a slice of life”, words often used to describe Anton Chekhov’s prose. Inge Bremer-Trueman grew up in Edmonton and as a young adult moved to Fort McMurray where she learned to fly airplanes and where she met her husband, also a pilot. A World Bank contract took them to Nairobi, Kenya in 1982. The sequel to A Root Beer Season is in its final editing stages. I can’t wait to read it when it’s published.

Exclusive FreeFall blog content! For more information about FreeFall Magazine check out our website.

I came for the root beer, stayed for the “familial tensions”, and am now intrigued by the “never boring”. Great review.