Kate Marlow

Kate Marlow

a review of

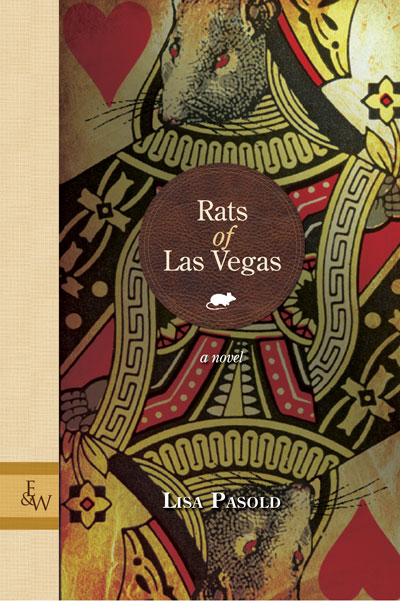

Rats of Las Vegas

by Lisa Pasold

Enfield & Wizenty

ISBN 978-1-8942839-2-2

$29.95

Lisa Pasold’s debut novel Rats of Las Vegas is engrossing, spirited, and impossible to put down. The story is classic: a strong-willed woman finds her place in a man’s world using her inherent talents and headstrong, resilient nature. Despite its familiar story arch, Rats of Las Vegas is anything bit clichéd. It could be the unique world in which Pasold’s protagonist flourishes that sets the novel apart from others of the same formulae – after all, how many books are written about a woman navigating Bugsy Seigel’s gritty world of Las Vegas poker? That could be it, but I suspect that what is even more special about this novel is Millard Lacouvy. In her protagonist, Pasold creates a fully-formed woman. Millard is so lovingly written and richly detailed that before you know it, Millard is not just a character in a book, she is a character in your life. And what a character she is! Millard charms her audience through an authentic dance between binaries: she is headstrong but flexible, bold but timid. Perhaps even more charming is the narrative distance that Pasold grants Millard. Rather than reporting on events as they happen, Millard reflects on her life from a future perspective, allowing Pasold to craft sage reflections:

Poker was the first fair choice I’d ever encountered: unlike the rules in the rest of life, poker allowed me to walk away if things didn’t look good. What else offered that kind of control over life? Where else would I be invited to play at life on the same level as any man, from any part of town? (48)

It is sentences like these, interspersed between plot developments, which fuel the incredible experience of being told a story rather than reading a book. These statements reflect exactly what makes Rats of Las Vegas such a charming book: as if reading a fairy tale, you are pulled into Millard’s world, and it is a world so compelling that you can’t bring yourself to leave.

The dance between binaries that makes Millard such a believable character extends from her own characteristics to the way in which her life unfolds. This most specifically applies to Millard’s relationship with poker: Sometimes she marches decisively towards her life’s calling. At other times, she is being pulled along by it, unable to escape its current. Interestingly, the shape of Millard’s approach to poker does not only alter the relationship that she has with the game, it also alters her relationship with the cards themselves, with luck and with the people that she has in her life. At a time when Millard is challenged by the game, she reflects: “I talked to the cards silently, they were like horses, fidgeting under our touch” (32). Here, Millard is reaching out to the cards, asking them for help in her game; they need coaxing. Yet when Millard plays well, she reflects very differently: “I can’t explain why the cards were my perfect key, a password to the world around me. All I know is that I recognized them as my saving grace, from the first moment I held them in my hands” (8). It is not just luck and sport that the cards represent to Millard. Rather, the cards have an agency that is much deeper. Through Millard, Pasold considers the cards in such a reverent way that a profound respect for the cards is woven throughout the novel. Pasold and Millard listen to these cards, and as a reader, so will you:

I took out an old pack of cards from my bureau, shuffled them, burned the top one and laid the next three in front of me. . . . I looked down at the three cards laid out on the bedspread. Three of Hearts – caution, eight of Spades – disappointment, and the King of clubs – an affectionate dark-haired man.” (259)

Millard’s fortune telling is not only touching because of the respect for the cards that she shows; it is also touching because at this point in her story, Millard is alone in Las Vegas, trying to make a name for herself in the world of Poker. She is alone, without the comforts of her British Columbia home, her family or her paramour. In Vegas, the cards are Millard’s only friends; it is only logical that they both provide her with company and offer her advice.

This use of cards fully realizes the fairy-tale feeling that Pasold executes: the cards are not just painted pieces of paper. The cards are friends, fortune tellers, a way of life, and a force of life. And, the are mystical: “[Cards] were invented by the Chinese, after they invented paper for money and for writing on. Cards grew logically out of such a combination – you layer paper with glue until it’s thick enough to endure the play of money. There: cards” (109).

This genesis story is Pasold creating exotic out of the every-day, infusing mysticism into the very subject of her book and as a result, the book becomes mystical.

In its protagonist, Rats of Las Vegas is familiar and warm. In its content, it is magical. If this combination doesn’t have you rooting around the junk drawer for an old deck of cards, it’s time to turn the book back to the beginning and start it again.

This review appears in FreeFall Volume XXI Number 1 Spring / Summer 2011