By Shane Neilson

Admittedly, faith is not a common lens for the analysis of contemporary poetry. As our culture hurtles forward along a post-faith trajectory that goes by the name postmodernism, some of the problems with the wholesale abandonment of what is called “religion” in scare quotes for secular preferences can be brought into view by taking a look at our cultural products that are increasingly symptomatic of a phenomenon memorably signalled by Eliot in his essay “Religion and Literature.” Eliot wrote, “I am convinced that we fail to realize how completely, and yet how irrationally, we separate our literary from our religious judgments.” What has come to pass is a replacement of religion as the unifying force for culture to postmodernism’s disunifying force. Let me consider Shared Universe as a chief example of the resultant confusion.

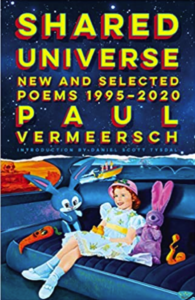

From the weak-messianic signal sent by the title, to the unexamined postmodernist philosophy inspiring the content, this revisionist text can’t escape the flaw in its premise: an attempted substitution of trusty metanarratives for a single silly postmodern one. The book’s introductory essay claims Vermeersch as poetic “visionary.” In an early review of the book published in The Fiddlehead, Travis Lane follows on this path, comparing Vermeersch’s work to Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. Because this mislabel is such an illuminating error, one that gets to the heart of the commonness of poetry like Vermeersch’s, I’ll stick on this tack for some time. I’ll then conclude this essay with a consideration of our putative visionary’s obscured origin.

What’s The “Visionary,” Kenneth?

In the midst of describing Vermeersch’s poetry as surprising, illuminating, and stirring, University of Toronto-Scarborough academic Daniel Tysdal’s introduction also describes Vermeersch’s poetry as “visionary” without offering a definition of what he means. Admittedly, Tysdal adumbrates what he means as he proceeds, mentioning Vermeersch’s “prophetic” verse that is written against the “rising Dark Age of our times,” but the use of “visionary” as a descriptor is, as it turns out, a real key to understanding Vermeersch’s work. I must bring forward a fair amount of preamble before I can directly engage with Vermeersch’s poetry because I don’t think we know, anymore, what “the visionary” is or means. But for now, to establish the relevance of this line of investigation, perhaps it’s enough to summarize that Vermeersch’s work consciously adopts a visionary stance on the basis of the following evidence: many poems directly channel the prophetic (e.g. “The Animals We Imagine”); a great many are thematically resonant with and formally mimetic of the bible (e.g. “I Became Like a Wooden Ark The Lives of Animals Filled Me,” “Liturgy For the Formal Exoneration of the Serpent in Genesis,” and even a section titled “Psalms of the Metaoccult”). The poems of this kind read as a postmodern wink at religion.

All readers passingly familiar with poetry have an implicit awareness that the term “visionary” is more than merely descriptive. Its religious connotations ring out, and most readers of poetry could offer Blake, Milton, and Rumi as examples of ‘visionary poets.’[i] To search for what “the visionary” is in modern poetry is to go on a curious adventure, but suffice to say I was eventually gifted “Visionary Poetry: Learning to See” by Hyatt H. Waggoner from a Sewannee Review article in the 1980s. Waggoner points out that

Blake, Wordsworth, Yeats, Emerson, Whitman, Stevens, and a host of lesser figures are all praised as visionaries, without it becoming clear what they have in common. A good many of the best-known contemporary poets produce verse that is quasi- religious in tone and reminiscent of myth in vocabulary, and we like to honour their work too by calling it visionary, though. It may express only nostalgia or despair and have little or no reference to any reality outside the poet’s mind. (228)

Waggoner nails something here that has to do not only with critical sloth and Paul Vermeersch’s work, but more pertinently a modern problem that’s with us because of the history of poetry itself. We might reach for the word “visionary” when we meet a poet like Vermeersch because we’ve lost an awareness of how inextricably linked poetry is from religion. We’ve buried this awareness in our minds somehow, making it an implicit but not explicit one, and when poetry that seems to know the bible and is comfortable adopting a prophetic tone walks along—like Vermeersch’s— we call it “visionary” without having to admit that this word lands very squarely in the realm of theology and religious studies. Or, as is our contemporary preference, we replace a religious vision with a secular, futuristic one and claim that, by virtue of merely discussing a future, the poetry is “visionary.” At work are two reasons, then, why one might call Vermeersch a “visionary” poet.

Winningly, Waggoner sends up the idea of attaching “visionary” to poetry at all in a way I think is relevant to the discussion of Vermeersch as visionary:

[C]an we agree on a meaning for it that can apply to poetry? Poet X was a true visionary, I say, but Poet Y as deluded dreamer and Poet Z a disappointed idealist who felt, mistakenly, that honesty required that he make do with a shrunken vision. We will agree, no doubt—when we share a common conception of ‘reality.’ Unfortunately we may not be around to welcome that distant day. Is there any way of agreeing, at least tentatively and provisionally, on what the marks of visionary poetry are, while continuing to disagree on the nature of ultimate reality and reserving the right to make our own choices of which visionary poets are the ones whose vision we can share, and therefore call ‘true vision?’

Though Waggoner himself relies on an ironic tone here, it’s important to recognize the constitutive subjectivity inherent to any judgement by individuals. We must problematize truth claims by any one critic, but not merely stop there. We must try to come to some tentative, useful claim about what it is we’re talking about—in this case, “visionary poetry.” For some critics, merely throwing a flag is a day’s work. But in my continued search, I keep seeing a flag that the past itself is throwing. There’s no way around consulting sources that focus religion. And on second thought, keeping Vermeersch and his oft-ventilated hostility towards religion in view here, how could there have been?

Enter Kinereth Meyer’s “Visionary Poetry and the Breaking of the Tablets” from Religion and Literature. After acknowledging that there is no one perfect definition, Kinereth offers the heuristic that “‘visionary poetry’ refers to poems in which the subject seeks, through the poem, to merge with a oneness (variously called God, Nature, the Soul), and to achieve a knowledge which is neither discursive nor logical but related[.]’” He tries to offer a definition that could apply to “modern poems,” and it is that such works are “nourished by a longing for wordless unity, and at the same time, for a dwelling in the multiplicity of language” (3) but qualifies this severely by acknowledging that “the critic finds it so difficult to even define the visionary element in modern poetry; one must be continually aware of the fluidity of this space, of the continuity of the discontinuity.” In short order, we’re shoved up against an inherent paradox: how can one keep all things in one’s vision to offer a unity, and yet write in a postmodern fashion? What is the oneness we can merge with that is not religious, keeping in mind that the drift of the culture is towards atomization? This is the challenge for the postmodernist visionary, to make the centre hold, and yet a postmodern artwork is meant to question what a centre is, to move or destabilize that centre, or to call it a purple elephant or Smurf. The contemporary visionary, it seems to me, is either left with an old-tyme religion, which won’t play well at awards tyme; or, they can try to create postmodernism itself as the unity, leaving postmodernism as the meaningful paradox; or, they can write out a weak messianic impulse poetry that, plus or minus, tries to offer postmodernism as its replacement for faith. Vermeersch chose the latter path, on the evidence that his poetry is chock-a-bloc with the cultural detritus of the late twentieth century deployed according to a postmodernist aesthetic sometimes thematically and formally homologous with a diluted Christianity. In the end, Tysdal’s label of “visionary” seems to fit.

Tasting This Visionary

Vermeersch’s poems, as do a host of his pomo contemporaries, cover pop culture. “As Fields Become Birds Become Clouds” is, like the poem at the outset of this essay, emblematic of my argument that pop culture pomo and a weak messianic impulse are Vermeersch’s non-unique version of visionary:

Drawing Snoopy on the mirror after bath time, this naked little boy in the steam, printing a thumb for the nose, then another, standing naked on the vanity, another white muzzle, another black nose, and the mirror, as fields become birds become clouds, an Escher of Snoopies. There is love at work here, and a solar system, and epochs crashing through time as floors through a levelled building. He is clean now, and the rest should be painless. The steam will evaporate, and the love, and the boy.

One notes the bric-a-brac of modern culture. Snoopy and the work of MC Escher inform the poet’s vision, just as Koko the Ape, Girl Guides, and Freud do in so many other Vermeersch poems. The perspective- change is beautifully enacted; the poem’s nonlinearity creates a huge range that takes in the specific and small (thumbprint) and moves to vast time (epochs) and vast space (solar system). There’s an apocalyptic feel, with the “levelled building” and the suggestion, at the end, of the boy disappearing/dying; the evaporation reads as symbolic.

To comment in formal terms, one notes the central single line as important, offering a visible suggestion of symmetry, as if one could place a mirror on the poem and see how Vermeersch tries to show a cosmos in a Blakean grain of sand. Finally, that it seems to connect with a speaker’s childhood is a common stance in Vermeersch’s work, something that isn’t coincidental in the thematic context of this poem, for as children we are at our most imaginative.

Yet Vermeersch’s chosen style is a problem not as style per se but in terms of its ubiquity. As John Nyman has written in Hamilton Arts and Letters Magazine on Matthew Walsh, that poet’s “force … comes through their emphatic lyricism mixed with broader self-reflection and, most importantly, a kind of whimsical ecstasy.” Nyman adds that Walsh’s lines are “marked by their interchangeability. Woven together, they create a kind of Kevlar irony-armour, employing humour and artifice to guard against sentimentality. This style is by no means foreign to postmodern poetics” (n. pag). This observation fits perfectly with Vermeersch’s work, especially the latter-day variety most intended to be visionary. “As Fields” doesn’t channel pomo as obviously as many other jokey/satiric poems Vermeersch includes in Shared Universe. Consider the apocalyptic glosa “What the Prophecy Could Not Foretell”:

That prophecy could not tell us that the layoffs would come on a Friday. That the palpitations would be caused by coffee. That the inventor of a childhood protected by monsters would die of an acute case of ghosts. There was no warning at all, no signs in the flight of birds, no dreams to caution us: the eggs would all be broken, the Internet slow. ESPN has announced the new sports set up again in Gaul, and from the world of Gauloise sport, one would arise to become Captain of the Humiliated. But the prophecy offered no caveat, no hint. The chocolaty sandwich-spread favoured by European children would consign the orangutan to scorch in the sunlight like a vampire. That boastful automakers on the verge of ruin would wage a PR war against sculpture. After victory in the Insubrian campaign . . .

This stanza sets the terms for the rest of the poem that comes after. A reader is dropped into a land of childhood loss, always Vermeersch’s power chord, one often oddly conjoined with the thematics of simians. The work is festooned with modern life’s bric-a-brac, ie. ESPN, slow internet, and PR wars. The level of distress feels miasmic, inherent in the cultural conditions (“palpitations . . . caused by coffee”) and, just as Nyman explained, the whimsy relieves us mildly from the ironic matrix (“chocolaty sandwich-spread.”) The poem continues in much the same vein, shoehorning in more bric-a-brac (“Boccioni,” “museums of Louisville”) and sinister modern innovations (“genetically modified turkeys”) in the subsequent stanza. The style is breezy, sharp, musically rich, and, I admit, even vaguely beautiful. The problem, though, is the work’s interchangeableness, how the bric-a-brac is random, yet a poem results. Vermeersch poems often create a vague atmosphere of dread somehow infused with the silliness of pomo juxtaposition, or they gesture to an ironized self-improvement through wackiness. That this poem is a glosa supposedly using a snippet of Nostradamus is apropos, for it formally frames the gathering that the poem enacts as a mild prophecy of some generic dystopia.

Perhaps we should think of Some Generic DystopiaTM as the unity that postmodernism offers, coming as it does so often in our science fictional cultural products? Other ironies lie in the discontinuous pieces of the postmodernist continuity that include Walsh, Vermeersch, and a host of other Canadian poets. For example, how can Vermeersch be considered a visionary when his kind of writing is of a piece with so much else? Shared Universe’s latter-day resequencing steamrolls what was distinctive about Vermeersch—more on this later—into a seamlessly integrated component of the aforementioned postmodern continuity. I happen to enjoy the latter as a reader, of course, otherwise I’d stop reading contemporary poetry; my point here is not to attack postmodernism as a style, but rather to demonstrate that Vermeersch’s work is hardly singular within that tradition of writing, and that a postmodern visionary is a contradiction in terms. Shared Universe is, therefore, a project doomed to fail in a predictable way.

Why, exactly, in terms of the poems themselves? Because, and let’s go back to “As Fields” and the many poems like it in the book, isn’t work like Vermeersch’s part of a swath of poems that are plangently vague, channeling a watered-down religious feeling that manifests now as awe at huge immensities like innocence, love, and spacetime? When Vermeersch writes “There is love at work here, and a solar system, and epochs,” we have the quintessence of Vermeersch’s vague visionary, offered almost always from the point of view of childhood nostalgia, his irony compromised because of the heavy reliance on the gears of the language itself as they were first developed in a religious milieu. Yet his work also attempts, at the same time, to find a unity in parody and random cultural items. Non-parodic poems fall in line too, straining towards some kind of grand cosmic impulse. The result, of course, is that our visionary artist is left where we are by postmodern poetry itself—unsatisfied, captivated by that culture, transfixed by its wonders, recognizing its beautiful ironies, but yet still relying upon the ancient structures and sentiments in order to carry the work.

Thus Vermeersch is less a visionary than a reactionary in several senses, reliant on recapitulating a standard postmodern art within the larger (and, frankly, far more multitudinous) bounds of religion, even if ironized religion. As Tysdal writes in his introduction,

Vermeersch . . . does not aim to rise above the world as the lone all-seeing knower. Instead, he demonstrates the value of this form of envisioning and expression, and, at the same time, he encourages us to undertake this same work, which demands our sincere attention and requires us to imagine and mull, to challenge and care. Vermeersch, then, employs the full range of his poetic tools to provide fertile models of composition to spur us to take part in the prophetic act. (7)

Tysdal offers Vermeersch as a small-v visionary, then, but this brings us back to the problem of ‘the visionary’ in the first place. If it’s used as a descriptor to mean a poet is suggesting a better way to live, then practically all poets do this. If it’s used somewhat more earnestly than that, but not capital-V visionary—and Vermeersch is at least at this level, as Tysdal suggests later in his essay when he writes of “Vermeersch us[ing] another foundational technique of the prophetic tradition: the development of a symbol for the societal, political, spiritual, etc.) threat”— then a weak messianic impulse serves as the originating spark for so much of this kind of writing. We’re far closer to a sublimated religion than we would ever care to admit.

References

Meyer, Kinereth. “Visionary Poetry and the Breaking of the Tablets.” Religion and Literature. 19.3 (1987): 1-14.

Nyman, John. “Across Time, Style, and Genre Via Vancouver.” Hamilton Arts and Letters Magazine. 2 July 2020.

O’Leary, Peter. “Poetic Religion: Forms of the Visionary Imagination” in Religion: Sources, Perspectives, and Methodologies. Edited by Jeffery Kripal. New York: MacMillan Reference USA, 2016.

Waggoner, HH. “Visionary Poetry: Learning to See.” Sewanee Review. 89.2 (1981): 228-247.

Shane Neilson is a poet, physician, and critic from New Brunswick.