by Donald Shipton

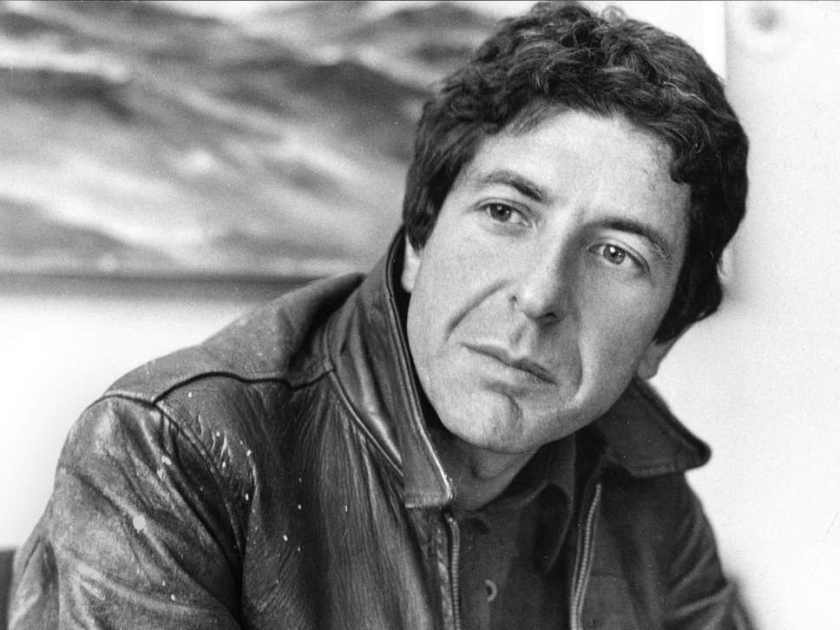

Leonard Cohen’s writing career spanned over sixty-five years and throughout this time, he made a profound impression on the tradition of Canadian folk music. Among his greatest contributions, is the practice of using religious texts as the metrical and conceptual basis for his music. Infusing ancient stories with his own reflections and vernacular, Cohen asserts the presence of the secular hymn in modern music. While many of his songs invoke biblical stories, none are more widely listened to than his magnum opus, “Hallelujah.” Maclean’s Magazine called it “the closest thing that pop music has to a sacred text” (Johnson). Like the Bible, which can be found in nearly every hotel and motel across the country, “Hallelujah’s” presence is nearly as sweeping. Sung in churches to remind parishioners of the cautionary tales of David’s adultery, or Samson’s foolishness; slurred and crooned in dimly lit karaoke bars; played faintly in the background of a teledrama; Cohen’s masterpiece is omnipresent in Canadian culture, although it does not always assert the same significance. A song about religion and love, “Hallelujah” is also an ode to the act of writing itself. Leonard Cohen worked on this song for many years and allegedly wrote eighty verses—some which have been read, most of which were discarded. Analysis of the seven recorded verses reveals as much about Cohen as it does his manner of faith. “Hallelujah’s” seemingly tireless composition contextualizes his belaboured form of worship and exemplifies the essential role of devotion in writing practices.

Leonard Cohen’s writing career spanned over sixty-five years and throughout this time, he made a profound impression on the tradition of Canadian folk music. Among his greatest contributions, is the practice of using religious texts as the metrical and conceptual basis for his music. Infusing ancient stories with his own reflections and vernacular, Cohen asserts the presence of the secular hymn in modern music. While many of his songs invoke biblical stories, none are more widely listened to than his magnum opus, “Hallelujah.” Maclean’s Magazine called it “the closest thing that pop music has to a sacred text” (Johnson). Like the Bible, which can be found in nearly every hotel and motel across the country, “Hallelujah’s” presence is nearly as sweeping. Sung in churches to remind parishioners of the cautionary tales of David’s adultery, or Samson’s foolishness; slurred and crooned in dimly lit karaoke bars; played faintly in the background of a teledrama; Cohen’s masterpiece is omnipresent in Canadian culture, although it does not always assert the same significance. A song about religion and love, “Hallelujah” is also an ode to the act of writing itself. Leonard Cohen worked on this song for many years and allegedly wrote eighty verses—some which have been read, most of which were discarded. Analysis of the seven recorded verses reveals as much about Cohen as it does his manner of faith. “Hallelujah’s” seemingly tireless composition contextualizes his belaboured form of worship and exemplifies the essential role of devotion in writing practices.

Leonard Cohen began his writing career at McGill in 1951. Initially enrolled in General Arts, he studied broadly and lightly, when he did at all (Simmons 33). During his period at McGill, he met writers who would come to be mentors to him; chief among them, were poets Louis Dudek and Irving Layton (Simmons 41). While Dudek inducted the young poet into the Montreal poetry scene, it was Layton who would come to be most influential upon the young writer’s form. Biographer Tim Footman notes, “One element that Layton encouraged from the beginning was the need to focus on his Jewish heritage” (22). Cohen’s fascination with the Bible began in his earliest years as a writer, and of course continued throughout the bulk of his career. What Cohen and Layton shared was an interest in Jewish scripture, if not for its theological merits, for its rhythm and poetic meter (Footman 22). Beyond religion, they both shared reputations as womanizers. In their poetry, each of them wrote candidly on sex, to ill and positive reception. Regarding his first collection of poems, Let Us Compare Mythologies, Allan Donaldson of the Fiddlehead disparaged his “overuse of images of sex and violence” (Simmons 53). Alongside what some critics might deem salacious, were rich reflections upon religion and love. It is at this reverent crossroad, where Cohen would find his voice. These early embraced themes blend nearly indiscernibly in “Hallelujah.”

One of the most common mythologies surrounding “Hallelujah” is that Cohen originally wrote eighty verses over the course of many years (Cheal). Laborious as it may seem, this claim aligns with what is known of Cohen’s writing practice. Singer Kathryn Williams said that his songs are “massively laboured over to not sound laboured” (Footman 9). In an interview with Sylvie Simmons, Cohen claimed that he and had written “Treaty” over the course of over 15 years and modified “Born in Chains” for nearly 25 years before its release (513). The precision in Cohen’s lyrics was not god-given, but instead the result of time and considered effort. He would not release a song or poem until it felt resolved, and what would finish as one song, might have been the product of tens of verses and years of reflection. As a lyricist, Cohen is often compared to Bob Dylan. Both were ethnically Jewish, wrote within the same period, lived at the famed Chelsea Hotel in New York City, and made folk music. Despite their frequent comparison, their writing practices couldn’t be more different. In a 1991 interview, Cohen shared an exchange he had with Dylan a few years prior. He said, “I helped out at a Dylan concert in Paris, afterward we went out to get a coffee together. He mentioned one of my songs that he played on stage, ‘Hallelujah.’ He asked me, ‘How long did it take you to write it?’ ‘Oh, I don’t know. Two years maybe, at least.’ Then I mentioned one of the songs from Slow Train Coming, ‘I and I’. He answered, ‘15 minutes.’” Years later, Cohen would admit that he had been dishonest with Dylan and that the song had in fact taken him much longer. In one interview Cohen said, “I wrote Hallelujah over the space of at least four years. I wrote many many verses. I don’t know if it was eighty, maybe more or a little less” (Light 3). When the song was first recorded in 1984, Cohen cut down the alleged eighty verses to four. The song begins:

Now I’ve heard there was a secret chord

That David played and it pleased the Lord

But you don’t really care for music, do ya?

It goes like this, the fourth, the fifth

The Minor fall, the major lift

The baffled king composing hallelujah

(“Hallelujah,” Various Positions)

In this verse, Cohen introduces the three main themes in his song: religion, love, and writing. He begins with his central character, the biblical musician and poet, David. In the book of Salomon, David would play music to ease the king’s mind: “Whenever the spirit from God came on Saul, David would take up his lyre and play. Then relief would come to Saul; he would feel better, and the evil spirit would leave him” (1 Samuel 16:23). In Cohen’s allusion to this chapter, he presents his personal use of music in worship, as a celebration of volition. Directly following the initial couplet, he hesitates before an audience. The second person, “ya,” might be interpreted as an ambivalent lover or listener. In either case, his pursuit of this secret chord is one verified only by his communion with God, and not through accolades. In the bible there is no such reference to a secret chord, this is an invention of Cohen’s. By adding this detail, there is an elusive quality to the song which David played, which Cohen replicates in the fourth and fifth lines. Rather than a “chord,” it is a chord progression. He describes this movement from the fourth to the fifth chord and the shift from a minor to a major key, reflexively, in the fourth and fifth lines. “The baffled king composing,” is not only David but Leonard Cohen too. This metaphor continues into the second stanza, which shifts from the first person to a second person perspective, and from the biblical David to Samuel. The second stanza reads:

Your faith was strong, but you needed proof

You saw her bathing on the roof

Her beauty in the moonlight overthrew ya

She tied you to a kitchen chair

She broke your throne and she cut your hair

And from your lips she drew the hallelujah

(“Hallelujah,” Various Positions)

The first three lines speak directly to King David who watched a young woman, Bathsheba, as she bathed on a roof below his palace in Jerusalem. Although she was married to Uriah, David invited her to his palace and slept with her. This allusion to infidelity mirrors what biographers frequently note in Cohen’s personal life (Simmons 86). The intimation that Cohen saw himself in biblical poets is clarified in the latter three lines through the story of Samson and Delilah. To the dismay of his family, Samson falls in love with a Philistine woman. Though he initially guards the secret to his power from her, she coerces him into revealing it, declaring they cannot love each other without total honesty (“Judges 16”). These final lines complicate Cohen as a romantic figure. These biblical women are presented as the source of the hero’s downfall while they are portrayed as objects of prayer. It is this muddled, objectifying worship of women-as-muses that makes Cohen such a polarizing writer for feminist critics. The third verse continues by questioning a prescriptive faith, echoing the secret chord alluded to in verse one:

You say I took the name in vain

I don’t even know the name

But if I did, well really, what’s it to ya?

There’s a blaze of light in every word

It doesn’t matter which you heard

The holy, or the broken hallelujah

(“Hallelujah,” Various Positions)

Cohen asks if the holy name is hallowed if not uttered in prayer. He argues that praise of any kind is righteous. Salman Rushdie once wrote of this verse, “only Leonard Cohen could get away with rhyming ‘what’s it to ya’ with ‘hallelujah’” (Light 25). This near rhyme inscribes the most prominent theme in this stanza: the irrevocably personal nature of prayer. Cohen uses “ya,” a vernacular word which signifies both you and yes to tease out the affirmative nature of prayer, and the need for an object of prayer— holy, or not. With the word “hallelujah,” he performs a similar function, albeit in a different register. “Hallelujah” is composed of the root word “hallelu” meaning to praise, and “yaw,” an abbreviated form of the name of God. By rhyming these two words—“ya” and “hallelujah”— Cohen argues that every word of prayer contains within it a holy sentiment, even if the words themselves are brusque. His mutable reading of prayer continues into the final stanza:

I did my best, it wasn’t much

I couldn’t feel, so I tried to touch

I’ve told the truth, I didn’t come to fool ya

And even though it all went wrong

I’ll stand before the lord of song

With nothing on my tongue but hallelujah

(“Hallelujah,” Various Positions)

The first two lines reveal Cohen’s attempts to reclaim emotional acuity through his music. Despite his best efforts, “it all went wrong,” and his music falls on deaf ears. The thematic refrain of “Hallelujah” culminates in this stanza, with Cohen’s realization that it is the utterance of prayer, and the volition, which is holy. This semantic crescendo is best summarized in his final line. While he sings “tongue,” the lyrics are often mistranscribed as “lips.” The difference is significant when one considers Cohen’s bilingual heritage. In French, there is one word shared for “language” and “tongue”: langue. This shared word draws together their mutual reliance; language’s indebtedness to articulation and articulation’s presupposition of language. However much the writer may edit and try to produce something great, meaning can be misconstrued and tainted. Therefore, it is not in the subject’s ears which Cohen’s prayer becomes holy, but upon the page, upon his tongue. It seems that like writing, prayer is a lonely practice. When one considers the numerous renditions of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” and its many thematic through-lines, the song can hardly be read as singular.

Hallelujah was originally recorded for the album Various Positions in 1984 with producer John Lissauer. Nearly thirty years later, Lissauer has fond memories of his time in the studio with Leonard. He recalls Leonard’s decisiveness: “there was no ‘Should we do this verse?’—I don’t think there was even a question of the order of the verses” (Light 17). Evidently, Cohen had made up his mind as to how the song would be recorded before he arrived in the studio. Lissauer reflects that “it almost recorded itself” (Light 17), but the ease of its recording was not mirrored in its distribution. After its recording, “[Various Positions] went to Walter Yetnikoff, who was president of CBS Records, and he said, ‘What is this? This isn’t pop music. We’re not releasing it. This is a disaster” (Light 31). In the heart of the 80s pop music boom, the market for depressive singer-songwriters was small. Yetnikoff might be attributed with the record’s slow reception, but he wouldn’t halt the process entirely. Instead of being printed in America, Various Positions was initially released overseas. Despite its stalled success, the album was picked up by PVC Records later that year, and it finally reached an American audience. Among the listeners was John Cale of the Velvet Underground. Cale was among the first artists to cover “Hallelujah.” He recalls, “After I saw him perform at the Beacon I asked if I could have the lyrics to ‘Hallelujah’. When I got home one night there were fax rolls everywhere because Leonard insisted on supplying all 15 verses” (Cale). Although far less than the rumored eighty, Cohen had given Cale more verses than were currently recorded. When Cale recorded his version for the album Fragments of a Rainy Season(1992), he added three verses which hadn’t been recorded yet. In addition to the new lyrics, “Hallelujah” received the benefit of a stripped-down production, with only piano and vocals. Two years later, using the same lyrics as Cale, Jeff Buckley performed and released his own rendition of “Hallelujah” to be released on his sole studio album, Grace. The vastly superior vocal range of Buckley married with the sparse production found on Cale’s version earned the song far more fame than Cohen had initially received for it. Buckley interpreted the song so beautifully that many forget that he didn’t write it himself.

Following the Jeff Buckley and John Cale covers, Hallelujah gained a new identity. In the version which Cohen releases in 1994, a recording from Austin City Limits in 1988, not only has the organ been exchanged for a guitar, but the lyrics have changed entirely. What was once a song rich in Biblical and musical references, is nearly entirely skewed in the direction of romantic love; no David, no Samson, just Leonard. Cohen writes on the song’s transformation: “[The original ‘Hallelujah’] had references to the Bible in it, although these references became more and more remote as the song went from the beginning to the end. Finally, I understood that it was not necessary to refer to the Bible anymore. And I rewrote this song; this is the ‘secular Hallelujah’” (Light 18):

Baby, I’ve been here before

I know this room, I walked this floor

I used to live alone before I knew ya

And I’ve seen your flag on the marble arch

But listen love, love is not some kind of victory march

No, it’s a cold and a very broken hallelujah

(“Hallelujah,” Cohen Live)

In the first two lines, Cohen entertains a feeling of recollection—perhaps looking back on what would now be a storied career not only as a writer, but as a musician too. In this verse, Cohen seems to respond to the themes he presented in the studio version just six years ago. In Various Positions, there was an optimism towards the nature of prayer; that regardless of the sign, it is volition that matters. Instead, he asserts in the new lyrics that love is not something that should be celebrated as a battle won or a great work of craftsmanship, but instead to be declared cold and broken. This stanza’s final line reflects “the holy or the broken Hallelujah,” heard on Various Positions. Notably, the holy is removed in favour of the cold. Referring to temperature rather than the ethereal, he evokes the bodily sensorium which the song continues upon in verse two:

There was a time you let me know

What’s really going on below

But now you never show it to me, do ya?

But I remember when I moved in you

And the holy dove, she was moving too

And every single breath we drew was hallelujah

(“Hallelujah,” Cohen Live)

In the song’s many verses, this is the most explicitly sexual. The first two lines not only carry sexual connotations but perhaps also refer to the song’s history; that there are numerous, less superficial ways to read the song as a text. Like a clothed body, its subtleties are hidden. In the final three lines, some of the religious motifs which Cohen teased out in his first version are revealed, but only through the act of sex. The consummation of holy love carries into the third verse:

Maybe there’s a god above

As for me, all I ever seem to learn from love

Is how to shoot at someone who outdrew ya

But its not a complaint that you hear tonight

It’s not the laughter of someone who claims to have seen the light

No, it’s a cold and a very lonely hallelujah

(“Hallelujah,” Cohen Live)

Rhyming “god above” and “love,” Cohen creates a harmony between the two. He begins by introducing God as a shaky object of meditation but answers his religious doubts by describing love. He doesn’t answer his own question, he points to their relationship instead. With this, he avoids any strict definition of God or religion and instead merely gestures. He continues to question even his own opinions in lines four and five. The verse concludes by playing upon the association of hallelujah, yet again. Rather than “cold and broken,” this hallelujah is “cold and lonely”; as if after the break, the prayer is alone. This again might refer to the act of songwriting. In Cohen’s live performances of “Hallelujah,” the musical break occurs just between the third and fourth verses, after the line “it’s a cold and a very broken ‘Hallelujah’” (Live In London; Songs From The Road; Live In Dublin). In nearly every one of Cohen’s performances, he finishes with the final stanza from Various Position, but in its new context, it rings differently. When he sings “I couldn’t feel, so I tried to touch,” the emphasis upon “touch” shifts from its emotional connotations to more sexual ones coherent with the song’s secular meaning.

Over the years, Cohen would all but abandon the original lyrics to his song, and during live performances, opt for a mix between versions, though sometimes playing all seven verses together. Given the popularity of the many renditions which followed his own, this performance is likely a response to other artists’ interpretations of his work. The song’s success is indebted to them. In 2006, R&B singer Alexandra Burke won The X Factor singing “Hallelujah.” That year, her recording of the song had sold over one million copies, becoming the top-selling song in the UK that year (Light 162). Merely by association, Jeff Buckley’s version shot up to number two and Leonard Cohen’s breached the top forty (Footman 206). Cohen saw his sales increase precipitously again after the release of the film Watchmen (2009) which used his song in its soundtrack (Light 176). Cohen recalls reading a review of the movie, where one writer called for “a moratorium on ‘Hallelujah’” (Light 175). Despite its wide use in film and television, Cohen’s renditions were often overlooked in favour of the Buckley and Cale versions. While both artists enjoy a vocal range superior to Cohens, the reason may not be purely musical. Where Cohen’s original studio version on Various Positions features dominant religious themes—attended by organ and gospel singers—later renditions such as the recording by Jeff Buckley are less overtly religious. He maintains some of Cohen’s references, but they appear alongside the romantic verses too, as a hybrid. When Cohen decided “it was no longer necessary to refer to the bible anymore” and rewrote the song (Light 18), he opened it up to a myriad of interpretations. The themes of love and craftsmanship which appeared alongside religion were granted more space and emphasis, and the song grew. Carrying the central hymn through its chorus, the song’s verses became more and more impressionable through their interpretations. The song accrued meaning, as a meme, throughout its various renditions, and in its progression fulfilled Cohen’s belaboured desire for a song which is both holy and broken.

Donald Shipton is a Calgary born writer currently completing his English degree at the University of Calgary.

Works Cited

Cale, John. “How Was He for You?” The Observer (1901- 2003), 2001, p. 137.

Cohen, Leonard. “Hallelujah.” Various Positions, Columbia Records, 1984. Spotify.

“Hallelujah.” Cohen Live, Sony Records, 1994. Spotify.

“Hallelujah.” Live In London, Sony Records, 2009. Spotify.

“Hallelujah – Live April 17, 2009; Coachella Music Festival, Indio, California.” Songs From The Road, Sony Records, 2010. Spotify.

“Hallelujah – Live in Dublin.’ Live In Dublin, Sony Records, 2014. Spotify.

Cheal, David. “It Was Originally 80 Verses Long – and 19 Other Facts about Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah.” The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 11 Nov. 2016.

Footman, Tim. Leonard Cohen : Hallelujah : A New Biography. Chrome Dreams, 2009.

Johnson, Brian D. “What’s with That Song ‘Hallelujah’? Leonard Cohen’s Masterpiece Has Become the Closest Thing Pop Music Has to a Sacred Text”. Maclean’s, vol. 122, no. 1, 2009, p. 68.

“Judges 16.” Judges 16 (New International Version), Bible Gateway.

Light, Alan. The Holy or the Broken : Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and the Unlikely Ascent of “Hallelujah”. Atria Books, 2012.

“1 Samuel 16 :23” 1 Samuel 16:23 (New International Version), Bible Gateway.

Simmons, Sylvie. I’m Your Man : the Life of Leonard Cohen. Ecco Press, 2012.