By Mary Vlooswyk

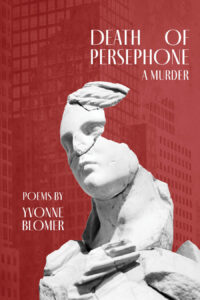

Death Of Persephone: A Murder

by Yvonne Blomer

Caitlin Press (2024)

From the title, one can deduce Death of Persephone: A Murder is about mystery solving. Blomer’s poetic narrative offers her readers connected mysteries; the fate of women walking alone at night, the appearance of paper whites, graffiti, and multiple unexpected deaths. I would like to note before proceeding that the book should come with a trigger warning regarding violence against women.

Mysteries are a great way to inspect the mechanics of society – what allows a murder to happen? By setting her poems in a mythological based world, Blomer uses the ancient past to reflect back on what is too common in our society. She isn’t arguing or persuading or comparing and contrasting, she is simply using poems to tell a story. Blomer’s unique approach presents the gods as if they were real. Uncle H. holds Stephanie captive as Hades did with Persephone, portraying very human strengths, weaknesses and limitations. From “Stephanie at the Museum of Fine Art”:

About suffering, the Greeks were masters—

bust of Zeus, nose cleanly removed,and Frederic Back’s environmental wail.

Stephanie whispers chiaroscuro to herself:what is shown and known, what is hidden,

she too full of contradiction: dark and light.

Death of Persephone is not for the faint of heart. I found myself queasy reading the poem “Violence is a bone in the body” where Blomer describes how violence bites. In “Case Notes: D.I. Boca No. 1/36” the poem shares the detective’s response to Beauty slaughtered. In “The Brothers think they are Gods”:

in one a darkness that homes in

on the girl, her sun-lit dress. Violence

And in the poem “Scratch”:

Out of nowhere – his fist knuckles the small of her back.

Skin and bone tracked and bruised.

He stands her upright, leans in as if

they are lovers.

Violence is embedded in the characters, each adding their own short-coming to the dark narrative.

Blomer’s premise is dependent on the evasive nature of violence throughout society where perpetrators do not celebrate the havoc they cause. It’s enough to enact the crime.

After the introduction of Stephanie, in “Dramatis Personae in alphabetical order,” the story proceeds with a growing understanding in the reader that something more than a single murder is underway.

If love is a battlefield, Stephanie is on the

battlefront and yet she is noncombative.

We don’t really learn much more about Stephanie until the poem “Delivery Day”:

…Uncle H. may have wished

for a girly girl, but she’s raised by a man, the Underground, in a space of men.

Truth disguised in the figures of mythology helps the reader make sense of the violence against women in the world Blomer creates through her poetry. “Pteropus: Fruits Bats” compares a bat to a young girl, there is movement from gentle descriptions to demonization and what happens to the girl. A foreshadowing of Stephanie (Persephone)?

Oh bat. Oh maiden child. Oh

myth makers and story

tellers. Look what we’ve done.

Demonized the bat, harvested it,

mummified it, sold it online,

stressed, starved, caged, poisoned it

Frozen it in vampire tales.

The perpetrators do not celebrate the havoc they cause. It seems the point is to enact the crime.

In the poem “The City” readers encounter a female graffiti artist. She appears again in “Case Notes: D. I. Boca No. 7/36”:

…on one

low wall, flaked white paint, a scrap of a shape

shining out—tail of a serpent slips—faded—

Blomer eventually introduces the reader to Thea, the graffiti artist, but her relationship to Stephanie remains obscure, as does the significance of the paper whites that appear with the graffiti at the various murder scenes. Blomer succeeds in offering haunting poems that capture the instability woven into the reality of women’s lives. The wild volatility and explosive unpredictability women face. Yet, somehow, they must keep existing despite it all.

The wonder of myth is how it touches moral codes. Blomer’s writing illustrates how the power of myth continues in modern times; how societal expectations simmer with anger and hope. Her poem “Corridor” unites myth, ancient history and the present:

Language the tongue cannot curl to,

yet tongues do. Persephone,

maiden taken, is in everything.

In ancient Greece women’s place was on the margins of society. Blomer challenges her readers to reflect and question whether time and social consciousness has created much difference for women. Can shining a light on Persephone serve to promote a feminine consciousness and empower women with violence lurking just out of sight? Blomer’s poems are beautifully written. Without sacrificing the details necessary to let them stand alone, they move from one to the next in a sweeping arc. They bleed into the story in ways that make it impossible not to pay attention to Blomer’s characters that haunt the night.

Mary Vlooswyk is poet whose writing has been published locally and internationally. She has been a contributing editor for Arc Poetry Magazine since 2019. Her first book of poetry, On the Prairie Fringe, was self-published in 2022. Her charcoal drawing, Surrender to the Wind was published in Shanti Arts. She is an adult student of cello. An avid lover of nature, she lives with her husband on the edge of beautiful Fish Creek Provincial Park.