by Anne Sorbie

by Anne Sorbie

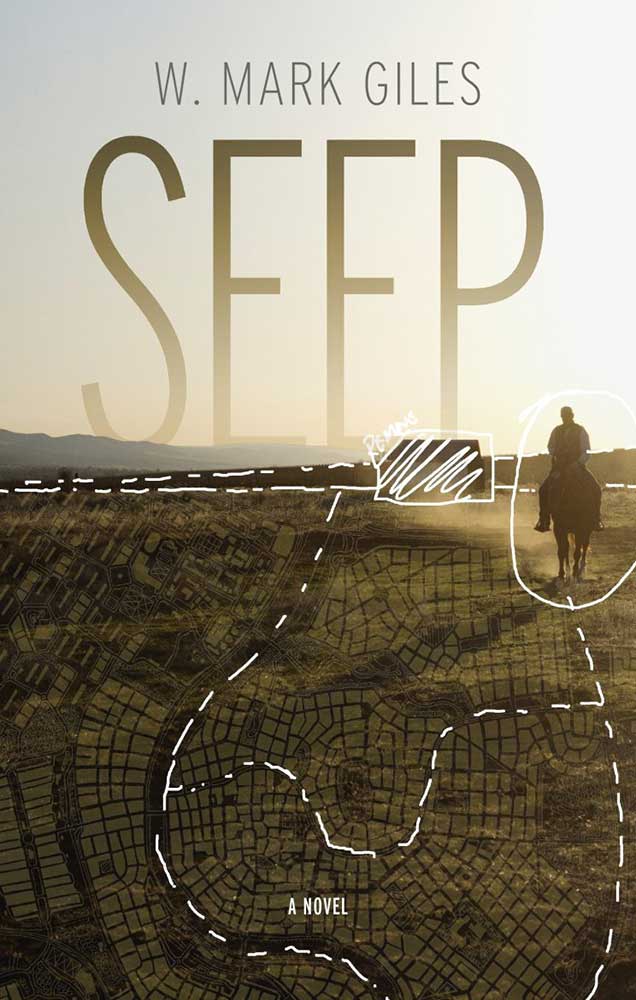

Seep

by W. Mark Giles

Anvil Press (2015)

ISBN 978-1-77214-012-5

Mark Giles’ first novel opens and closes with explications of “once upon a time.” The approach is playful, but, rather than nudging us toward fairytale the novel encourages

reflection on subjects such as narratology and cultural analysis. Some of you might read these same sections, and much of the book as a whole, as a post-modern offering, while some may consider Seep, as I do, to be a glorious example of prairie-noir.

The cover blurb says the book is “a wickedly wonderful account of how our senses of self and place can be interrelated…” Two of the strongest narrative analogies for that are a much fought-over piece of land and…to keep us in deeply anchored in the theatre of the absurd…shiplap. Overlapping wood siding that was once typically used on the outside of houses. Board-like, barn-like: material for preserving notions of home. As an example, consider the scene in which the main character unexpectedly sees his childhood home on a giant transport truck rolling down an Alberta highway.

The novel, we are told, follows “in the footsteps of…W.O. Mitchell…[and] Robert Kroestsch” and Seep most certainly does. Although I’ll suggest that this novel goes further. It goes beyond the marvels of our spectacular western Canadian landscape, and

beyond absurd events underlined with comic relief. Seep is filled with a strong sense of place that is centered in a fictitious town of the same name. Seep and two of its nearby

municipalities, Malcolm and Caxton, are modeled on the Alberta towns of Seebe,

Canmore, and Cochrane. Like Seebe, it was also built by a Utility / Power Company to

house its workers. It is situated east of Malcolm (Canmore) and west of Caxton

(Cochrane). Seep, like Seebe, perches high above the Bow River on its north side, where

water cascades, at scheduled times, from the sluice gates of the Horseshoe Dam. And

like Seebe, the town of Seep is accessed by a one-lane bridge over the Kananaskis River

where it meets the Bow. Here the rivers are a confusion, pooling and eddying against

and away from the dam the way the two brother characters in the novel are both

bewildered and satiated by their congenital addictions.

Seep is an excellent setting in which to ground a complex narrative; the town is an

archetype of the absurd, the strange and the unique. Like Seebe it is a proverbial ghost

town. It is also mired in cycles of stasis and flux as developers try to master-plan-

manipulate it into an exclusive and excruciatingly expensive offering of high-end

mountain properties. The supporting characters echo real-estate types, first-nation

original owners, environmentalists, and local ranchers who are all in an ongoing fight

with the utility company for power over – excuse me – for the right to protect – that

same small tract of land. It is in this extraordinary location that Giles’ novel tackles the

archetypal battle of and for power and control; both are imperative, both are physically

and metaphorically interrelated on every level of this story.

The Horseshoe Dam at Seebe / Seep, remains integral in the control system of vast

amounts of our Province’s best natural resource: water: water flowing out of and into

watersheds that include Spray, Minewanka, Kananaskis, Ghost, and the North

Saskatchewan. Organically the geography provides the kind of substance required for a

quintessential Kroetschean story. And all the elements of the absurd converge here. For

example, in stories from the main character’s childhood such as the one in which a

baseball game includes an unexpected outdoor birth that occurs below the bleacher

seats while the game ends in an all-out brawl. Giles creates for us the perfect conditions

for a multi-thematic offering of prairie-noir, enveloped in the pure complexity of “once

upon a time.”

In Seep the tragic theme of the histrionic, alcoholic led, addict producing, wholly

dysfunctional, (Caucasian) Alberta family is front and center. And let me be clear,

examples of it exist today in the thousands. The gravitas and the degree of dysfunction

in the book provide multiple hooks and are just a couple of the reasons the novel

earned a place on the shortlist for the Amazon First Novel Award. In Seep, the classic

abuser’s acrimonious behaviors are alive and well, delivering in the narrative a shock

and awe depiction of intergenerational trauma. It is the sort that survives and lurks like

a virus taking over the body and mind of the father character and presenting later in his

two sons. The younger son is “Dwight” and he may, or may not we are told, really be

called Dwight. Ditto for his older brother, “Darcy.” (My use of quotation marks here,

mirror the use of the same by at least one of the narrative voices in the novel.) “Dwight” is a gambler and “Darcy” is a beautifully conceived example of a self-centered, drug-using, do anything, anything at all to get what he needs, people-abusing alcoholic. Their

father Lance, who was a doctor, suffered from each of the aforementioned addictions.

Lance also had an addiction to sex. With women. Women to whom he routinely gave

abortions.

Unrestrained abuse is hyperbolic in Seep. Overlapping like the shiplap on the old family

home. As a reader I could not help but grasp the degree and depth of dysfunction that

explodes the narrative. There is a bizarre turn of events in the book (one of many)

during which Lance drinks himself to death and expires on the living room floor. While

his wife sits in a chair and watches as presumably his liver and other organs fail, causing

blood and other matter to be expelled from his nose and mouth. And although Lance’s

death scene is exquisitely conceived, horrific, and deeply disturbing there is another

scene, which I will propose exceeds it and which is perhaps the most shocking in the

book. That scene takes the narrative further than the level of mere spectacle and it does

so because of that incubating virus I spoke of earlier. And I am about to tell you about it

in the context of what I believe is possibly its worst form.

At the tender age of ten years old, “Dwight” beats a dog to death with a section of

shiplap. In his own words he tells us that he uses, “…not the whole piece, but the

bottom half, peeled off [of the house in which he and his family used to live” (17). And

he does this after the aforementioned shiplap is used on him by “Darcy.” And after

“Darcy” demands “Dwight” kill the dog. After the older brother has already used the

same weapon to break the dog’s back. What occurs in this scene is a direct result of

learned and internalized paternal abuse and sociopathic tendencies. It is here that we

have narrative proof that the virus has indeed been incubating. “Dwight” does what he

is instructed and goaded into doing: he beats and beats and beats and beats the dog

until he and his brother are covered in canine flesh and blood. After this, “Dwight”

carries the dog murder memory with him into manhood. He strokes it the way he does

the rolls of bills he sometimes has in his pockets if he wins in the casinos he visits. But

only sporadically. From time to time. Maybe once every ten years. When things get

out of hand. When “Darcy” shows up. This reader carried that scene with her

throughout the narrative that followed and beyond.

Seep is a story of the histrionic, of an alcoholic led, addict producing, wholly

dysfunctional Alberta family. In this novel addiction fed abuse bleeds out and goes

beyond the underbelly of the story. Addiction fed abuse is the vehicle that leads us

through the physical and into the metaphoric. It is used to create arc in the narrative

structure. Used to great advantage amidst elements of the theatre of the absurd

provided by the confluence of character and place. Seep is a book that will satiate a

deep readerly need in those who enjoy stories about warped concepts of “home,”

dysfunctional families, and homespun harm. Shiplap. Overlap. Seep is an example of

pure post-modern, prairie-noir, a complex “once upon a time” narrative.

Anne Sorbie’s fiction, poetry, essays, and book reviews have been published by Inanna Publications, The University of Alberta Press, Frontenac House, House of Blue Skies, and Thistledown Press; in magazines and journals such as Alberta Views, Geist, and Other Voices; and online with Brick Books, CBC Canada Writes, Geist, and Wax Poetry and Art. In 2019 she published a chapbook titled, Songbook for a Poet, (which envelops thirteen poems by Robert Kroetsch and thirteen by Anne). Her third book, a collection of poetry called Falling Backwards Into Mirrors, was published by Inanna Publications in October 2019.