By Vivian Hansen

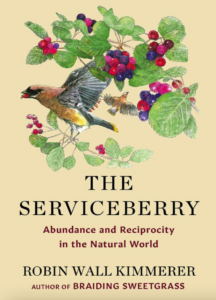

The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World

by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Simon & Schuster (2024)

I pluck the easy-going Saskatoon berries, a few sacrificial ones for my mouth, and a few that speak ‘plunk’ in my pail. In the dog days of summer, thirty days after the summer solstice, the berries are ripe. My cousins pivot around me, looking for their own voluptuous branch of Saskatoons. My mother, sister and aunts are stepping around the mud paths to gather as well. I cannot think of Saskatoons, or Serviceberries, without recalling this scene of matriarchal, matrilineal labour that bonded us. We would make pies soon, and with heavy cream, eat the fresh berries for dessert.

The Serviceberry is the model that Kimmerer uses to advance her thesis of how the gift economy can work and mitigate against the oppressive capitalism. In an interview with Jenny Odell from Orion Magazine, Kimmerer reflects:

We cherish a gift for the relationship it embodies. When we use it, it is wrapped in

gratitude. When we use a resource, it is clothed in entitlement. (November 19, 2024).

What of this gift economy? How is it an improvement over abject capitalism? The notion of gift implies freedom of reciprocity. Kimmerer delves deeper: “To name the world as gift is to feel your membership in the web of reciprocity. It makes you happy – and it makes you accountable. Conceiving of something as a gift changes your relationship to it in a profound way, even though the physical makeup of the ‘thing’ has not changed.” (22) Scarcity produces in consumers the desire for something that cannot be held or had. Kimmerer asserts that “if there’s not enough of what you want, then want something else.” (77) This direction upholds diversity, allowing the earth to fallow and wait for another day. Industrial economies are short-term, and a slide of gift economy is more adaptable to human need. Kimmerer reverts back to Serviceberry economics: “…I don’t see scarcity, I see abundance shared: photosynthate is usually not in short supply, since sun and air are perpetually renewable resources.” (78) “Market and capitalism demand that abundant, freely available, earthly gifts be converted to commodities and made scarce by privatization and high prices.” (79). So, this line of thinking: to possess, oppress and own the earth is crazy, and to use a scary cliché: unsustainable. Gift economy begins to look like a desirable option.

Gift economies flourish in a small community, where commodity is less appreciable. Kinship locates in more robust forms within groups that embrace gift economy. Kimmerer upholds a wish:

I cherish the notion of the gift economy, that we might back away from the grinding

system, which reduces everything to a commodity and leaves most of us bereft of what

we really want: a sense of belonging and relationship and purpose and beauty, which

can never be commoditized. (90-91)

When a gift economy flourishes, we enjoy music, poetry, scent, and the blue, wealthy taste of a Serviceberry.

Vivian Hansen’s publications include three full-length books of poetry and several chapbooks. She has published essays in Coming Here, Being Here, and in Waiting. She also has a short piece in the Calgary Public Library Dispenser Series (2019) “Where We Surfaced.”