By Mary Vlooswyk

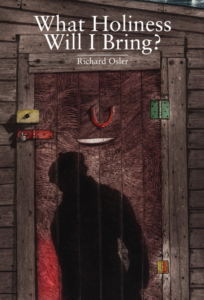

What Holiness Will I Bring?

by Richard Osler

Frontenac House (2024)

On July 5, 2024 Richard Osler shared news of his esophageal cancer diagnosis with readers of his Recovering Words blog. He summed up his post paraphrasing Hala Alyan, the poet he had featured, to describe his own journey, “As it appears my tide may be coming in hard and fast, I want to keep remembering beauty.” On October 26, 2024, he exhaled his final syllable. In that short span of time, he was able to complete a manuscript of poems he had been working on and gift his followers, What Holiness Will I Bring?

Death is inevitable, but somehow, our society relegates death so far from life that we barely acknowledge it exists. Death will arrive whether we find a convincing way to write about it or not. In the pages, Osler is unapologetically himself and does not shy away from writing about his fast approaching death. His poem “Ordinary March” tackles this twisting and twining of life and death:

I am a mirage caught between life

and death, a mirabelle no less marvelous

for arriving, maybe soon, at an end.

A mirabelle, a wonderous beauty. Richard’s belief that beauty will outlive us all shines forth from this poem and the whole collection. Seeing beautiful requires an openness to noticing. It requires trust in a gentle, powerful force beyond typical understanding and allows hurts to be shaped into something we never thought possible. In “Do You Dare Enter”, Osler suggests seeing beauty involves an open has to do with our perspective, and maybe a sense of awe:

Try to remember who you are. Say hallucinations.

Say phantasmagoria. Neon birds in cages. Breathe.…Be puzzled/and intrigued. And begin to let go. Let forms

seduce you and whisper poetry. Let forms change

your seeing.

Osler finds a way to transcend the exhaustion that often comes with the process of loss. In this slender volume of compact and, rich poems Osler weaves his story through the subtle brushstroke of his pen. We are able to witness him develop a type of confidence, or release to in the flow of his life and the winding journey it has been taking him on.

When joy feels so very unrealistic, I can remember Richard’s distinct laughter as he delighted in so much of the world around him, reminding us to consider where glimpses of joy might be. His poem “Sing” suggests that in the midst of hurt, sorrow and celebration can coexist in a heart:

I say to the world

be my open mouth,

sing your joy,

your sorrow, back to me

so that I may sing joy

and sorrow back to you.

“Sing” is Osler’s call to connect, to share, to touch one another through a song that is greater than darkness. This was a key theme in Richard’s teaching and healing workshops. There was a strong sense of community, a circle of energy that was alive and sparking. Easter Catholics have a tradition of lighting a candle in the dark and slowly sharing the flame from candle to candle until the entire church is filled with light. Richard had the ability to do this in his workshops without actually using a live flame. Osler’s poems carve a path from his heart to the page and into the world. His poems ask his readers how each will use our voices as beacons of beauty and connection. Even when his world looked nothing like he thought it would, Osler had the ability to deem life a gift.

When days unfold in hard ways it can feel impossible to understand why. “Poet and Chair” is a poem in which Osler carries the invisible weight of grief for a dear friend. The poem uses repetition to express the inexpressible, inconsolable loss. In a dark hour, 5 o’clock, is forever etched with the essence of the poet’s friend. The repetition becomes elegiac praise. Praise of time and its passage. The moment of loss, a moment filled with itself, taking the thoughts causing commotion in Osler’s mind and transforming them into a holy moment:

…I was not there

and I had no chair to hold an

impossible weight,so I asked my love for a thousand legs to hold me.

If ever there were a perfect moment to have a crisis in one’s belief it could be in the middle of inexpressible pain. But Osler does not let a Stage 4 cancer diagnosis, processing his dear friend’s death, or dealing with complicated health struggles affect his unwavering faith in poetry as prayer. Perhaps his belief was strengthened by his work in recovery centers where he witnessed the dramatic healing power of poetry help those in recovery from addiction become reacquainted with parts of themselves through their own words expressed poetically. Perhaps the divine, or deeper part of himself was being accessed when he wrote “Poet and Chair 1”, where the poet desires:

…something evanescent, a death –

wish of sorts, to prove a lack of fear of disappearance,

or fear of nothing lasting, to poke a finger at any adherenceto an idea of infinity, to bless always the fleeting moment

for what it is and see its quickly-going without lament.

Osler acts as a beautiful minister for his readers as he considers one’s spiritual alignment with eternity, mysteries long pondered by philosophers and theologians, in “The Family of the Poet”:

…And a poet worries

words to make sense of what he accepts, refuses

to understand, his own death coming. No excusesstand up to what each death demands. A family

its grief above ground and every hidden profanitycaptured between clenched teeth. The graveyard

its own quiet family and a poet holds loss in a jar.

Hurt shapes us. Osler’s poetry is subtle, honest, sincere, heartfelt. He is true to a faith, something greater than here and now. His cancer diagnosis brings his beliefs into sharper focus and he delivers poetry with a calm grace. Osler invites us to move from tears. He presents his poetry as an offering to grief. Each poem succeeds in quietly, subtly, seducing us into its grip. We are ensnared into currents of words that lead us to our own contemplation of life and death. Life is difficult. If it wasn’t difficult, it wouldn’t be special or interesting. We’re all focused on our own holy struggle. Osler offers his poetry as a way of setting the chaos of existence into some kind of reassuring order. He shares his intimate beliefs as in his poem “An Ekphrastic on a Postcard Collage of Stained Glass”:

And the soul – does it stay or does it go? I imagine it

curious but slow as it moves. I imagine it as it leaves

the body, surprised, but sure enough not to look back

in regret. Not to look back at all.

To see beautiful one acknowledges what is, and accepts what isn’t. It’s offering to use what you learned through your hurt to ease someone else’s pain. It’s taking what is in front of us and creating something beautiful from it. This is the holiness that Osler brings.

Mary Vlooswyk is poet whose writing has been published locally and internationally. She has been a contributing editor for Arc Poetry Magazine since 2019. Her first book of poetry, On the Prairie Fringe, was self-published in 2022. Her charcoal drawing, Surrender to the Wind was published in Shanti Arts. She is an adult student of cello. An avid lover of nature, she lives with her husband on the edge of beautiful Fish Creek Provincial Park.