by Jannie Edwards

by Jannie Edwards

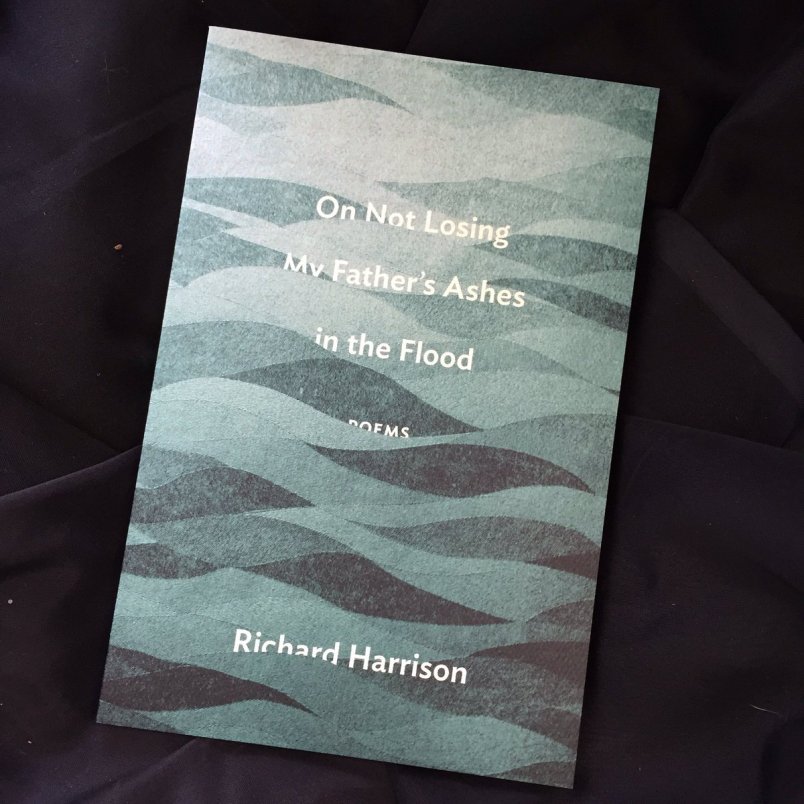

On Not Losing my Father’s Ashes in the Flood

Richard Harrison

Wolsak and Wynn (2016)

ISBN 978-1-928088-22-6

There is an invitation, a hospitality in Harrison’s work in his eighth collection. The reader is invited to share the poet’s intimate experience of his father’s life and death, the feared loss, and retrieval, of his father’s ashes in the epic Calgary flood of 2013, and what it means to write, read and recite poetry, to find meaning and purpose in life.

Time and space. Life and death. Expansion and confinement. As the father’s health and memory deteriorate and he is confined to a palliative bed and wheelchair, the poems’ lines spread back and forth like waves that range over a lifetime. In good measure, the hospitality of these poems comes not only from their subject matter but also from these long lines — tiered, indented long lines that are less about creating architectural structures and more about breathlines, about creating space for the reader to inhabit.

In “Small as God,” father and son enjoy riffing a list of the father’s close encounters with risk, injury, disease, near-death close calls: POW, heart attacks, a stroke, skin cancer. And, then, his father’s offers “one more / Fifty years of marriage, he said, / barely squeezing his words through his wheezy laugh.” The poem ends with the father repeating one word—Catastrophic—a summation of a life that is neither expansive nor disruptive, but rather one word uttered in a last room: “You never know how solitary a single room can be / until it frames the portrait of your reach and grasp.” I was reminded again that the origin of the word stanza is “room.”

As his father’s life narrows “as furious as / a man with memory confined to minutes could be,” what he returns to are lines of poetry that “have him by heart.” From Shakespeare’s Richard III: “Now is the winter of our discontent / made glorious summer by this son of York;” and from Dylan Thomas’ “Fern Hill”: “Though time held me green and dying / Though I sang in my chains like the sea.” What the poet comes to realize is that poetry offers his father a way to speak through these words the “savage and gentle contradictions” of his heart. Poetry as code, an encrypted way to decipher the soul’s reach and yearning.

The great Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz in his questioning poem “Ars Poetica?”: “The purpose of poetry is to remind us / how difficult it is to remain just one person.” And so begins Harrison’s ars poetica, a questioning of the mysterious, alchemic art of poetry, trying through poetry not only to understand his father as a complex human being, but also to try to understand the mysterious art of poetry, beginning with the poetic lines his father recited all his life. These lines of poetry, these repetitions are not echoes, not cover songs, but rather in the struggle of tensions and opposites, in the pull between the discontent of winter and the glory of summer, poetry becomes a mirror, becomes a map, becomes the psyche’s barometer, a way into plumbing intimacy.

In “Greatness,” the speaker listens to his father’s midlife reciting of “Fern Hill” on an almost obsolete cassette tape recorder. Technology becomes as unreliable as memory in preserving the past. In dramatic counterpoint to Dylan Thomas’ sonorous poetic voice, his “church bell grief,” Harrison’s father speaks the poem “as though a child was sleeping next to him whose dreams he whispered into but would not dream of waking.” And these words recited again from a hospital bed: “You haven’t heard / Time held me green and dying / Though I sang in my chains like the sea / until you’ve heard it from the wizened mouth / of a man in the not-knowing-when before his death.” From “Greatness”: “A line can sum a life. And this was his.”

Reading these poems sparked memories of my own elderly father recovering from a massive stroke. Remarkably, he began reciting poetry and singing nursery songs in French, his first language. He was not alone. Among the heartbreaking wails of anguish up and down the stroke ward, other elderly stroke patients were rediscovering primal neural pathways opening to poetry, song, prayer and in one case, loud, angry swearing. I am haunted by the memory of a frail white-haired woman strapped into a wheelchair recharging and unleashing her pent-up rage through violent curses.

Harrison acknowledges his ambition as a poet, confesses he is “greedy for the mouths of poetry and words spoken / in ways they have never been spoken before.” He experiments with fresh metaphors: “Poetry is play, even in the darkest of its discontents / Poetry is a sex abuse victim, / shoulders back, roaring out of the body alive;” and “Experience is to a poem what a belly button is to a mammal.” His father teaches him “the poem is a bed of gravel / the rain could not wash away / a sheet of particleboard cut clean with a knife — not a saw, / the sideways glance you use to find a contact lens on the carpet.”

In “The World Made New,” the poet witnesses his father losing his memory: “like watching fireflies in a forest, / each one a fragment of light, / but not so great a light to keep away the darkness.” Memory is fragile, unreliable, and contradictory. Like poetry. I wonder how the Imagists, recalling their urgent poetic challenge to “Make it New” would respond Harrison’s closing metaphor in this poem. Caught in the obsessively recursive loop of dementia, he says: “Around we’d go / in that darkness together — / trapped in that terrible excellence / poets long for in every poem / that moment words have no past and in them the world is made new.” Poetry as a kind of crazy god game. A kind of dementia. A terrible excellence indeed. And, of course, this metaphor undermines, destabilizes the entire project of the book, which is to witness a mind at work, mapping the great desire of a seasoned poet to find the words to document the ineffable — death, grief, philosophy, joy — a kind of beautifully doomed, eternally unfinished project which distills consciousness in the midst of transience. Yes, “Everything changes, even extinction” he writes in “A Poem in the Arms of Tyrannosaurus Rex.” But this is balanced against “Let us say the poem is not / what we feel / but what we have learned.”

In “Maps and Writing Paper,” the poet acknowledges, “Everything has already been written / yet I still write as if there is something new to find.” For Harrison the poet, “every object is a kind of page / every life a kind of writing.” Time writes on the body. Technology writes our subconscious lives. What he learns in this project paradoxically moves through words, beyond words to wordless sound, images, and, profoundly, touches. From “This Son of York:” “My father taught me a poem is not its words, but in the ringing it leaves behind.” In “Ode to a Temporary Urn,” the poet claims the superiority of impermanence, referencing the plastic urn which houses his father’s ashes. This, a rebuttal to Keats’ famous “Ode to a Grecian Urn” which argues that art transcends time and death.

And touch. The image of the poet holding his dying father’s hand persists in memory and, ironically, through words, through poetry, keeps his father alive: “This poem is alive because it is unfinished. / My father is alive, / and I am holding his hand, / his hand is pale, and blue, and violet, / a trembling garden of irises.”

Jannie Edwards lives and writes in Edmonton. Her latest collection of poetry is “Falling Blues,” from Frontenac House. Jannie is the vice president of the Edmonton Poetry festival and a professor emeritus of MacEwan University.