By Vincent Potter

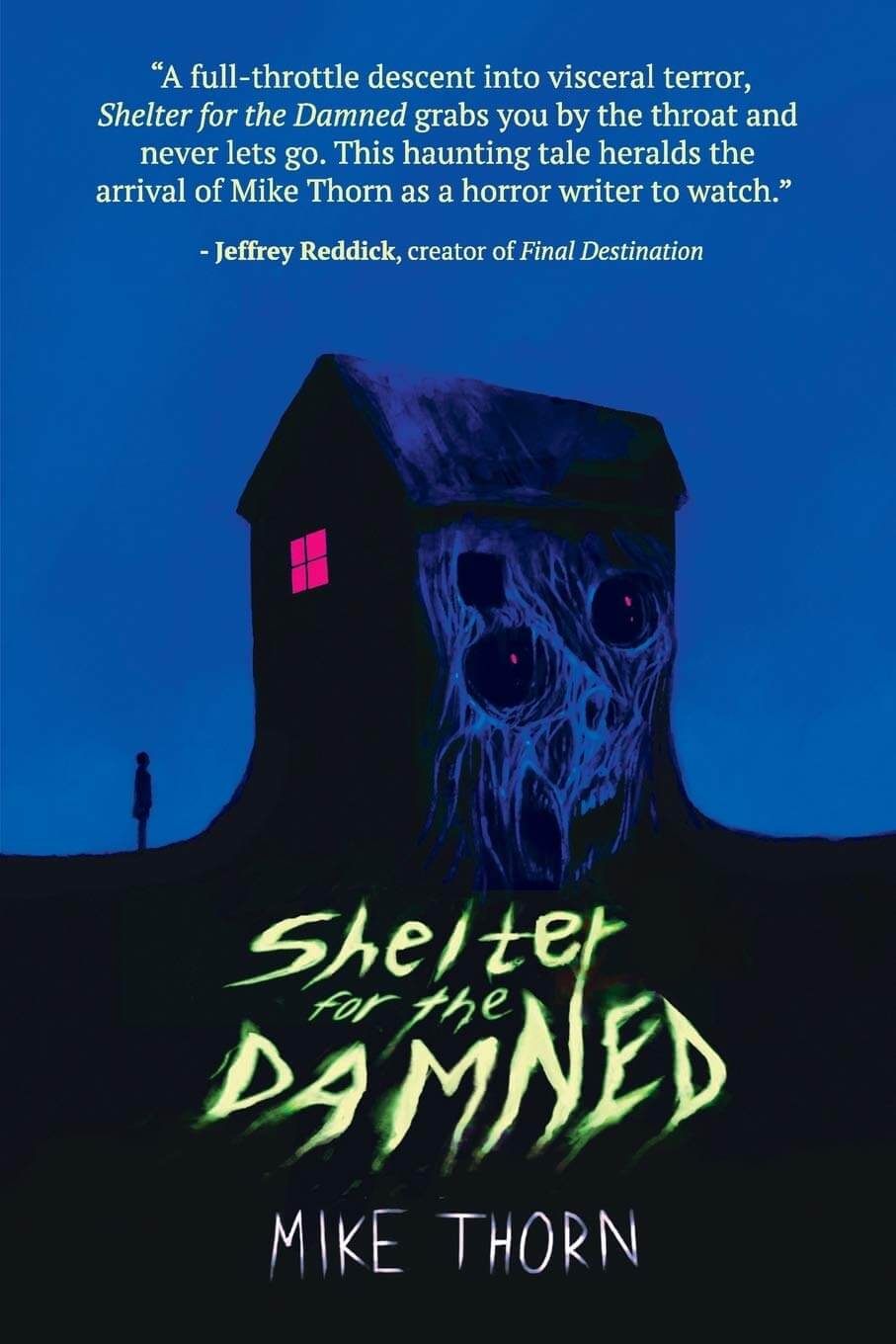

Shelter for the Damned

by Mike Thorn

JournalStone (2021)

“They sat for hours, talking dirty in the rot and gloom. Mark had never taken so long to smoke a cigarette. He half-listened, but mostly he just breathed. Mostly he just felt.”

Mike Thorn’s Shelter for the Damned reads like a slice-of-life centered on a budding heroin user—a coming-of-age story with a downward slope. Its horror comes not from the boogeyman in the shed, who scares protagonist Mark less than it should, but from a beached-fish helplessness, a starvation for air. Mark is burdened by nothing in particular and desperate for something he never articulates; he is the manifestation of many the lost teenager, those who go out not in a bang but in never- ending spirals of criticism and confusion. He doesn’t fit. He starts brutal fights by accident and resents his punishment. He’s angry and doesn’t understand why. He can’t speak out, even to his parents. The burden of living in a world that tosses him backward as it pleases is already apparentfrom the first chapter, but only worsens as the novel progresses. And then there’s the shed.

If Mark is a drug user, walking into the shed is his first hit. Inside, the turmoil of his life melts away, and Mark is instantly addicted—not to what the shed is but to what it isn’t. There’s no expectation in the shed. There isn’t anything in the shed. During the first visit, Thorn writes, “[Mark] couldn’t explain exactly what he felt in that moment. Sort of an ebbing…like he’d just been caught up in the best film he’d ever seen, and for a few seconds had actually forgotten about the world outside the screen.” Like shooting up and floating away, Mark finds a sort of barrier world inside the shed: a place where no one knows where he is or asks him to answer for himself, where there’s nothing wrong with him because there’s no one to compare to and no one to judge.

Perhaps a more disappointing aspect of the story is that there is, in fact, something hiding in the shed. The aforementioned boogeyman plays a steadily increasing role in the novel, and Thorn uses the entity to drive Mark over the edge of madness. But the entity itself isn’t particularly unique or surprising—what’s more interesting is how the shed urges Mark back with incredible strength, and how the monster uses this addiction to its advantage, entrapping Mark in an unescapable partnership. Like an addict dating his dealer. The physical description of the entity feels unnecessary to this relationship, and for long-time horror readers with high tolerance for spooky creeps, this devil-emerged may have come across more terrifying if it had simply stayed in the shed’s walls, whispering from the attic, never quite revealing itself as being either paranormal or psychological.

It could also be said that Mark’s father, perhaps the one person Mark is truly afraid of, is a bigger threat to the boy’s sanity than the beast in the woodwork. When first reading the novel, it’s clear that Mark (like those he represents) is not unfixable; Mark is incapable of asking to be fixed. He doesn’t even understand what’s broken, and no one is making the effort to identify it; instead of adapting to meet Mark’s difficulties, the characters at his home and school pound him into the same hole as every other student, then unload their frustration on him when he doesn’t fit. Mark’s father is a well-written proponent of this cruel project to hammer Mark into shape. Instead of a more-obvious abusive father who drinks and hits and yells, Thorn writes Mark’s dad as quietly threatening, doing, and saying just enough to keep Mark on edge while maintaining a pseudo good-guy dad act. It’s near-impossible for Mark or the reader to tell what’s going on inside the man’s head, but the small flashbacks and glimpses of the father’s true nature are enough to spin a tense red thread beneath every interaction. Even his dad jokes are eerie in context, as the reader is never sure when the act will slip. With all these violent, uneasy undertones stinking up the household like dead rat rotting in the drywall, Thorn makes it clear that Mark is doomed from the start. This is not a place for reaching out about ambiguous, confusing difficulties; this is a place for careful silence and selectively chosen words.

Shelter for the Damned proves that reality is more frightening than fiction. Thorn’s scariest characters and scenes are those that feel less like they come from a story and more like an experiment to see what happens when an all-too-familiar lost adolescent is split more and more from his family, friends, and reality—like prying fingers off a cliff’s edge, one by one.

Vincent Potter is a Calgarian writer and editor. Since graduating from Mount Royal University’s English program, he fills his time with freelance editing and writing poetry next to his guinea pigs. He is a prose editor for FreeFall Magazine.