By Angeline Schellenberg

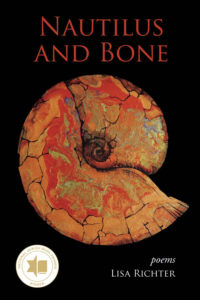

Nautilus and Bone by Lisa Richter

Frontenac House (2020)

ISBN: 9781989466124

I’m usually drawn to poetry books that feel like old friends: collections that put music to my own experiences of domestic prairie life. Especially during a pandemic, when my concentration is faltering, it takes a strong lyric to pull me into an unfamiliar narrative. Lisa Richter’s poetic retelling of the life of Yiddish-American poet Anna Margolin, with its sensuous language and fantastical images, did just that.

Nautilus and Bone, a member of Frontenac’s 2020 Quartet, is the Toronto poet’s second full-length collection. As she explains in her introduction, Richter’s kinship with Anna Margolin (the pen name of Rosa Lebensboym, 1887–1952) includes the fact that Richter’s great-grandfather was a Margolin (she imagines him handing Anna his name like a string of pearls) and that in Anna, Richter recognizes her own parents’ wild and sensitive spirit.

Writing in the persona of Margolin, Richter labels the collection an “auto/biography.” Like trying to extract flour from cake, it’s impossible to discern where Anna ends and Lisa begins. Margolin’s poems and the records of her life meet Richter’s memories and imagination in a delightful blur. “I look in the mirror, cough up my snarling double. / She sticks to the glass and demands compensation” (98). The book itself is a mirror: is it Margolin or Richter looking back at us?

This is particularly true in the poems aptly titled “Marriage” that pair Margolin’s terse poetic lines with prose poems that expand the spaces between Margolin’s words.

Within each poem, there are other meldings, as inner and outer worlds flow together: “I fitted my mouth around your short / stout stump, tasted the sea salt- // tinged wind, blousing cool through a hotel window –” (39). We find a mingling of the human and the natural, public and domestic, in “molasses crowds” becoming “the sluggish river that floats // me home” (40).

The world of Richter’s imagining is a magical place where “the grandfather clock metronomes me into wishbone sleep” and “vertigo lifts me in its beak” (29). She takes us from Europe to Palestine to New York, through neighbourhoods equal parts comical and dire, in which “three crooning drunks share a single pair of pants,” a girl is instructed to “take [her face] off and put it on again,” and the “newsboy [fishing] for his childhood” finds “a human thumb” (32).

As she transports us into both Margolin’s physical setting and her state of mind, Richter’s words hold more than their weight in meaning, the way “swell” in a single passage can suggest wombs, wounds, and waves:

So much bounty, we could hear the sculpted legs groaning. In those days the poems would not relent, swell

after vertiginous swell, my open wounds wild-stung with salt. An ice-blue pain I came to savour. (98)

In describing Margolin’s marriages, male and female lovers, and unwanted advances, Richter’s skillful use of enjambment plays up the innuendo with line breaks such as: “I am a phoenix many men have tried to mount // on their walls” (47).

Nautilus and Bone invokes the senses in ways that are both fragrant—the “coffee’s earth-deep / buttered loam” (51) and, as Anna explains why she is an only child, guttural—“what man / can stomach a litter of rotting pears – / all that split, mealy skin, oozing pulp, / squandered juice in a lonely orchard’s shade” (20).

Like brittle bone and shell, these poems preserve the memory of a revolutionary poet—a legacy both fragile and enduring.

Angeline Schellenberg’s Manitoba-Book-Award-winning debut, Tell Them It Was Mozart (Brick Books, 2016), explores the ache and whimsy of raising children on the autism spectrum. In 2019, she published three chapbooks and was nominated for The Pushcart Prize and Arc Poetry Magazine’sPoem of the Year. Host of Speaking Crow, Winnipeg’s longest-running poetry open mic, Angeline recently launched the elegy collection Fields of Light and Stone(University of Alberta Press, 2020).