By Katherine Matiko

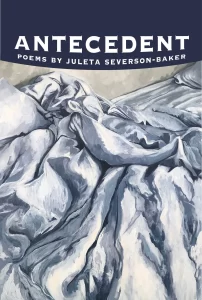

Antecedent

by Juleta Severson-Baker

Frontenac House (2023)

Juleta Severson-Baker dedicates Antecedent to her ancestors, so it was no surprise to

encounter a boy coming to terms with life and death on the prairie (My Father) and the

multigenerational impact of a child’s drowning (The River).

But as I read further, I was surprised to find myself in so many of these evocative poems.

For example, Severson-Baker writes eloquently about the loss of her mother. My sisters and I recently became “motherless girls,” as the poet puts it, in the fifth and sixth decades of our lives. We, too, experienced “how wolves wake so quickly / and bite so hard” when chronic illness descends (My Mother of the Stiff Upper Lip). Like the poet in The Best Part of the Story, I have glimpsed my mother while watching my sister “wipe a table with a cloth; her hand, her shoulder / taking her space . . . Her ghost the colour of night behind falling snow.” And when loss rises so brutally and unexpectedly, it is best to decide that the “weight of grief / needs heaving into the river.” (Sorrow)

Like Severson-Baker, I have felt the futility of comforting a spouse when a parent’s death is “a cold wash of certainty,” as inevitable and overwhelming as the Bay of Fundy tides (As My Mother-in-Law Was Dying I Went for a Run on North Medford Road). The writer captures the loneliness of death in Twelve Months Later: she wakes thinking about her mother-in-law and how “no one can come fully / into another’s suffering / no matter how much / they love you.” She implores this particular “antecedent” to know that “we were with you / we were with you / we were as close as we could be.”

I could identify with the poet’s exploration of midlife, a season of loss and contemplation but also promise and rebirth. In Everything on Repeat?, she longs to feel the wind again but is mired in the ennui of middle age, where nothing is new under the sun:

“This hour, this bed. Inertia

after coffee, too many screens,

worlds pretending they’re not

this world. Too many words. I look out

where air is moving, and ache.”

But in Remember Lac Cardinal, the “wind takes thoughts / to the tops of middle-aged poplars / gives them a good shake / I’d forgotten how / when I was a girl / I went with the wind.”

In the Remember poems, Severson-Baker takes us along on her memory trips. I loved the happiness described in Remember Pereau Road, another Nova Scotia poem. The poet is on a walk, and “back at the house, a farm-market chicken roasts. / A log burns simply, almost lovingly, in the woodstove. / No need to turn back yet. You might / walk all the way / to Blomidon. / You might remember / this moment. / Yes. You are sure you will.”

And then there are the fascinating Debbie Poems, A Self in Four Acts, in which the poet stands shoulder-to-shoulder with her “old selves” (and Everywoman) to dissect “fractal” memories of childhood, adolescence, and middle age, and the plague of self-loathing borne by women of all ages. In these poems, I once again discovered “shimmering, chimeric” pieces of myself (The Characters).

Katherine Matiko is a poet living in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains where she finds daily inspiration for poetry. Her poems have appeared in (M)othering: an anthology (Inanna Publications); Wild Roof Journal, Issue 17; the League of Canadian Poets’ Poetry Pause; and WordCity Literary Journal, Spring 2023. One of her poems was among the winners of Fort Calgary’s 2024 Chinook Poetry Contest.