by Daryl Sneath

by Daryl Sneath

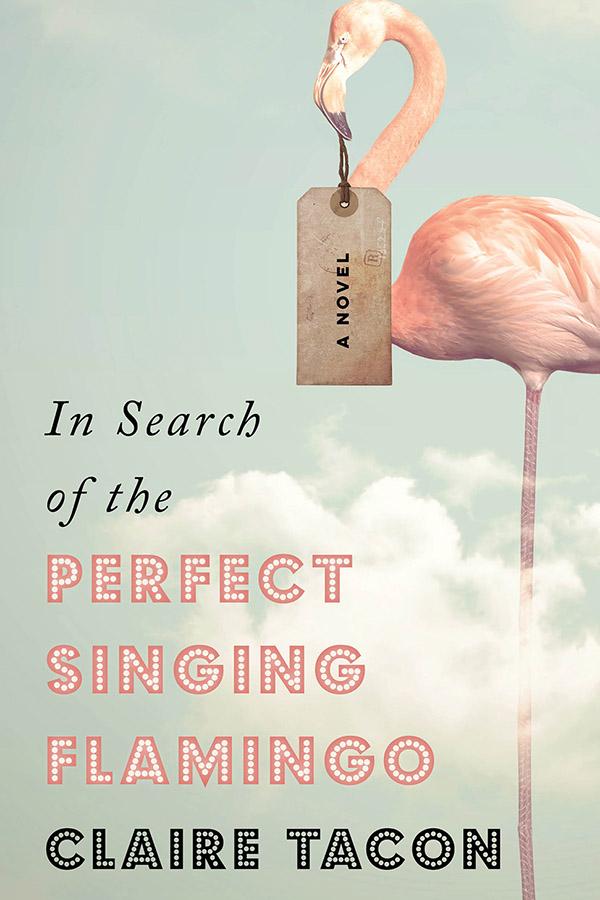

In Search of the Perfect Singing Flamingo

Claire Tacon

Poplar Press (2018)

ISBN 978-1928088578

Lead and driving force that she is, Starr Robinson is no ordinary hero. Born with Williams syndrome, she has not been dealt an easy hand: sometimes she feels beaten before she begins, sometimes she does not know all the rules and cannot help question

them even when she does, and sometimes she holds a deck’s worth of hearts right up against her own, staunchly unwilling to part with a single one. Among a myriad of other well-drawn traits it is these—her laid-bare, uncompromising heart, her uncensored voice, her utter resolve—which make us love her.

Told in a quartet of voices, the ‘search’ in Tacon’s sophomore effort is equal parts

adventure, contemplative reflection, social treatise, and unconventional redemption song.

Darren Leung works with Starr’s dad, Henry. Along for the ride (both literally and

figuratively), the sometimes morose, unabashed believer-in-love-but-heartbroken

teenager, Darren, wants nothing more than to rekindle a relationship with Luz (the ex-

girlfriend archetype with whom he shares a love for film), but in the end, he worries that

all his efforts will earn him nothing more than “another shank to the heart.”

Melanie, Starr’s sister, wants to begin a family of her own but faces fertility (and

subsequently financial) difficulties in doing so. It is no narrative and thematic accident

that Melanie spends her days coordinating set production and managing the personalities on a home reno show. Behind the scenes facilitating the perfect place for families to come home to, she is the ‘fixer’ and knows too well that her “life is a countdown to responsibility.” If only she and her husband could have their own moment (not that she wants the spotlight, content as she is to remain behind the scenes) “before the pressures of senior and sibling care compound.”

Enter Henry, Starr’s dad (whose perspective bookends the novel), the anti-patriarch with

a soft heart and a quiet presence who wants only to make Starr happy. Like his other

daughter Melanie (and too often she does feel like the ‘other daughter’), Henry is in the

‘fixing’ business, too. A mechanic of animatronics, he repairs the brought-to-life

members of the band Starr loves. Taken a (larger-than-life) step further, he has acquired a working version of said band which sits in a room in their home like an interactive

museum piece (one of the many images of a ubiquitous past). Utterly dedicated to his

daughter’s happiness, Henry embarks on a cross-border journey (Starr and the lovelorn Darren in tow) to secure the one missing member of the animatronic band Starr loves: the perfect singing flamingo.

Structurally, Tacon’s work keeps company with novels such as Barbara Kingsolver’s A

Poisonwood Bible and Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wonderous Life of Oscar Wao. Subject-

wise, it shares space with Jodi Picoult’s House Rules and Kim Edwards’s The Memory

Keeper’s Daughter. Stylistically, there are notes of Alice Munro (quiet, subtle moments

of revelation, starkly drawn), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (understated and at times

overtly stated comments on race and gender politics—a resonant chord Tacon struck with subtle complexity in her debut novel In the Field), all tempered with a unique and

striking turn-of-phrase. Case in point: early in the story Henry approaches a table in a restaurant where his wife, his daughter, Melanie, and his son-in-law await his return and

he thinks to himself, “The three of them are eyeing me with wary anticipation, as if I’m

an amateur magician and they’re not sure if the pigeon I summon will be dead or alive.”

Everything Tacon summons here hums with energy and purpose, captured perhaps most

starkly by the juxtaposition of the unexpected: so-called ‘high’ art alongside ‘low’ art (an

auteur’s installment-production called The Human Pincushion which makes last-minute

use of a Frankie’s Funhouse squirrel mascot); classic literature allusions rubbing elbows

with contemporary luminaries (Gatsby references, a Chuck Palaniuk cameo, and an

unforgettable shout-out to the ruby hues of Oz: “her lips could have been cut out of

Dorothy’s shoes”); and, not to be forgotten, a pair of innocently smuggled turtles who

unwittingly cause all kinds of problems.

In Search of the Perfect Singing Flamingo, at its core, is a search for hope. It is a novel of

independence overcoming perceived powerlessness, of misunderstanding and

acceptance, of letting go. It is a novel of reparation and reclamation. An announcement of our driving desire to know, to love, and to change. It instructs us that although it may feel sometimes that we are borne back ceaselessly into the past, all we can do is beat on

against the current because, as Henry tells us (rewriting the Carraway message rather

plainly), “We won’t be going back.”

Daryl Sneath was born in a small town by a lake. He has a number of stories and poems published with Canadian journals and magazines, such as TAR, Prism International, The Dalhousie Review, Nashwaak, Filling Station, FreeFall Magazine, and The Literary Review of Canada. He has also written for the New York publication Weekly Humorist. His two novels are All My Sins and As the Current Pulls the Fallen Under. He now lives in another small town by a river with his wife, Tara, and their three children Ethan, Penelope, and Abigael.