By Catherine Owen

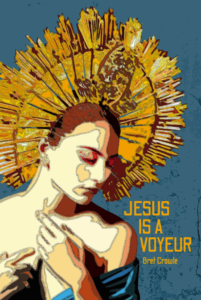

Jesus is a Voyeur

by Bret Crowle

Frontenac House (2024)

Fugue: a contrapuntal composition in two or more voices involving repetition. The plurality of everything. Jesus: purported savior and experiential voyeur. Mental illness: another kind of vision and a societal condemnation. Sexuality: a sexcapade bounty and a source of inscribed shame. In Bret Crowle’s debut collection, Jesus is a Voyeur, she draws many of the threads together that inform a female-shaped psyche: familial and religious expectations, fraught attractions, recurrent depressions, questions of fertility and pervasive bodily experiences. The connections repeat, both within the poems themselves and inside the book’s flow, a weaving of anaphora and punctum, echo and haunting. Crowle adapts villanelles, haibuns, pantoums, and ghazals to this essential yearning, to return to words that pinpoint, inhabit, articulate, ghost. The poem that beckoned first was “Honey” with its delirious nursery rhyme sonorities: “Flick of the wrist, dismiss. Blood/ stains panties. It’s time for the talk. Birds and the bees flutter. Wing to wing./ A bumblebee hovers, an open door. /One and a-two, three and a-four.” Most of these sounds recur throughout the piece, re-shaped as questions or within alternate contexts. A vital technique.

Other poems also benefit from this fugue-movement: “Playmates,” “Ornament,” “Drumheller,” “The City is a Voyeur,” and “Self-Portrait.” The directive, “Carry on,” reappears. Dividing poems called “Intrusive” are curios of transformation where “cum rags” become “origami swans” and falling stars startle. The list poem called “What Can You Have?” is an unrelenting move from East to West as allowances and exclusions are slapped down: “You cannot wake up next to your girlfriend without guilt, cannot have comfort./ You can know that the church will never approve of four breasts sharing one bed.” There is an Anne Sexton vibe throughout, a desire to unabashedly reveal, express, oust; a dark fairytale eroticism.

Some pieces might be stronger performed, such as “Loiter” with its filmic stutters of “Inhale;” “Exhale” and “Tick Tick;” some would be more potent without clichés like “bathed in sweat” [“As July Afternoon Drifts from Drumheller”], awkward inversions such as “No closer could I be to God/ than where time doesn’t exist” or pedantic conclusions: “I can only leave when I understand, believe/ how God can scorn those/ composed by the biology and religion/ created by His hands” [both from “Schadenfreude”]. Writing poems that aim to encompass these massive subjects and transform singular subjectivities into acts of necessary communication is indubitably challenging. A piece like “Slots” achieves this apex by mashing all these energies together: mental illness, sexuality, parents, religion, and shifts with painful speed between various angles, the segments divided by bracketed perspectives like “[denial]” and “[projection].” Then, at last, in “The Holiest Place on Earth,” Crowle turns towards nature for a deeper, non-judgmental solace and has “a chat with canola stalks” as the crow becomes a “prairie angel,” that transfigures the language of Psalms. Jesus is a Voyeur is a collection of potent poems about identity’s multitudinous transfigurations within the abject and magical body, an unwavering fugue of truths.

Catherine Owen is the author of sixteen collections of poetry and prose including her latest, Moving to Delilah (Freehand Books, 2024) and The Weather Says Poems (Carbonation Press, Washington, 2024). A born and raised Vancouverite, she teaches, edits, reviews, and gardens from her 1905 home base in Edmonton.