J.D Mersault

J.D Mersault

A review of:

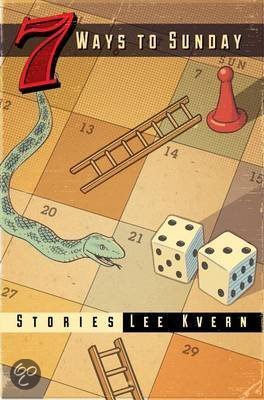

7 Ways to Sunday

By Lee Kvern

Enfield & Wizentry

ISBN 978-1926531854

Lee Kvern’s recent short story collection, 7 Ways to Sunday, succeeds in bringing its readers a rich world of descriptive prose and a depth of reflection rarely found in the high realist tradition of the Canadian short story collection. When I first picked up the book, I felt the nervous sense of foreboding I often experience when I’m expecting to delve into some identity-based Canadiana. Was it going to be another book of Canadian stories that happen to Canadian people that live in Canada? I know little of Kvern’s oeuvre, but from what I had heard and read, I was expecting to be in for a lot of ink about the Great White North, and the good white people living in it. Not so. Or, at least not entirely so.

This is the tension in Kvern’s collection – found here is the almost folklorish contemporary Canadian tale, rife with images of the brusque RCMP officer, the cold, clear prairie morning, the desolate small-town supermarket, the 30-packs of cheap beer, and Export “Eh.” There’s nothing wrong with this kind of genre in itself, but the point to be made is that it is in fact a genre – and with any genre writing, its good when it’s good, and so, so bad when it’s bad. Middle ground is hard to find with such specific subject matter, even if as Canadians we’re supposed to be comfortable with compromise.

Nevertheless, Kvern’s take on the genre is charming in a familiar way, but also exalted with sheer precision: the banalities of the downhome Canadian setting are displayed here on a knife-edge. This uncanny vividness in the face of desolation is found throughout Kvern’s collection, but especially in the third story, the shortest of the thirteen, Fourteen. Here, in a local Sobeys, we’re hit with a trenchant metaphor: a lobster about to be boiled.

“He watches the boy struggle to put the lobster in the too-small box. The boy folds the tail down while forcing the lobster’s fettered claws into the box. When the boy manages to do both at the same time, the lobster rears up from inside the box, its antennae poking out, waving around one last time before fate and cardboard close in. Both man and boy appreciate this last stand for different reasons: the boy admires its feistiness, the man, its struggle – however futile”

A quiet scene, but don’t mistake quiet for incidental. There’s a real emotional heft to Kvern’s prose. Again and again, Kvern’s knack for the emotional gut shot comes through. The title story near the end of the book treats us with another hit, as the protagonist, Miles, speaks with laconic ease to a pair of Jehova’s Witnesses.

“So what’s on for today?” Miles asks. Glances sideways into the neighbour’s yard where the single mother in a white halter-top is filling up her Beauty and the Beast swimming pool with the garden hose for seven squealing kids. She runs a daycare but the majority of the kids are hers. Miles thinks to tell Brother Kevin that he and his wife Mern, only have one daughter, Joleanne

“Mern was seventeen when she had Joleanne and after that she couldn’t have anymore. Tubal pregnancies. Nothing to do with me,” Miles says.

“My bullets are gold.”

This sparseness is then variously contrasted with a rhythmic, cascading, dreamlike prose suggestive of some of the more dynamic contemporary stylists writing today. Kvern’s prose swings, as it were, both ways. The Pynchonesque names of many of her characters, although unbelievable in some manifestations, add to the surrealism. Pali Caliente and Atticus in Beautiful Morning, Jaxen and Chase in White, Kade and Loyola in Lead, and the elusive Lucinda in In Search of Lucinda. In the experimental Beautiful Morning, this shift in style, as well as setting, helps move the book itself through a kind of arc. Here, instead of the author’s current surroundings, the story takes places along the banks of the Hudson. Refreshingly, Kvern’s sentences stretch out with the river.

“Pali knew the litany/legend of his body art, the skipping, stippling tattoos, so naughty, nautical, scrimshaw-like, elaborate drawings on a minuet scale displayed across the cagey surface of his salted skin, first in Pali’s mind as she watched him across the crowded room behind the makeshift bar. Then later with Pali’s soft mouth and renewed hands, every lucent pore of her Spanish body finding them, discovering him bit by bit like bits of startling treasure washed up on shore or tiny illuminated glints half buried in the sand, beneath his clothes.

Refreshingly, 7 Ways to Sunday demonstrates Kvern’s emotional and intellectual reach beyond the stereotype of the small-town Canadian author’s short story collection. But then, this is more of an anthology, or a greatest-hits album than merely a collection of recent work. Kvern has consolidated these stories from twenty years of work, and this is one of the pleasures a book like this can offer: A reader can begin to see an author’s transformation as their career contracts and expands. In Kvern’s stylistic experiments, although much of the work in 7 Ways to Sunday could more convincingly now be described as canon, Kvern seems to have a firm grasp on her experimental potential. And, again reassuringly, the reader can trust Kvern to excite both their imagination and sense of home.

J.D. Mersault is a writer and visual artist from Canada. His art theory and review has been published by the Art Gallery of Alberta, and The New Gallery in Calgary, his fiction has been anthologized in the Calgary 2013 Biennial of Contemporary Art, and and his criticism and memoir has appeared internationally in The American Reader. His sculptural work has been exhibited most recently by the Epcor Centre for the Performing Arts, and the RBC New Works Gallery in Edmonton. He currently lives in Calgary, Alberta where he is recovering from a long and misspent education in philosophy.

J.D. Mersault is a writer and visual artist from Canada. His art theory and review has been published by the Art Gallery of Alberta, and The New Gallery in Calgary, his fiction has been anthologized in the Calgary 2013 Biennial of Contemporary Art, and and his criticism and memoir has appeared internationally in The American Reader. His sculptural work has been exhibited most recently by the Epcor Centre for the Performing Arts, and the RBC New Works Gallery in Edmonton. He currently lives in Calgary, Alberta where he is recovering from a long and misspent education in philosophy.

Excellent review of an excellent book