Marilyn Letts

Marilyn Letts

A review of

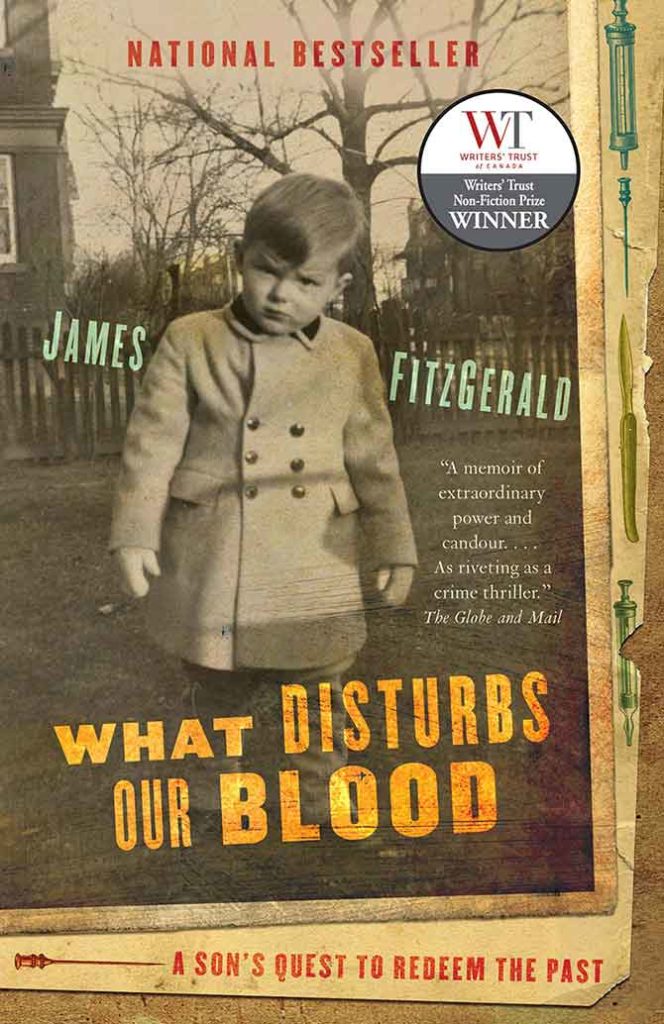

What Disturbs Our Blood: A Son’s Quest to Redeem the Past

by James Fitzgerald

Random House Canada

ISBN 978-0-679-31315-1

$34.95

What Disturbs Our Blood: A Son’s Quest to Redeem the Past by James Fitzgerald is an ambitious undertaking. Anyone who has tried to redeem their own individual past can imagine the difficulty of trying to reclaim the account of the previous generation, let alone the past two generations. Add to that the family pattern for men to flame up in a brilliant career and flare out in midlife in depression and suicide attempts. Fitzgerald weaves his family story together with the larger history of psychiatry, health care and wealthy Toronto society, all of which influenced his family. He rescues the story of his grandfather Dr. Gerald Fitzgerald’s contribution to the beginning of public health and the discovery of insulin. And he recounts his father Dr. Jack Fitzgerald’s influence on the establishment of immunology as a medical specialty. This seems like sufficient recovery to claim that his quest is a success. However, he goes beyond the past to take what I consider the greater challenge: attempting to live in a way that redeems the past by exploring his own emotions and fragility and sharing with readers some of that struggle.

Fitzgerald begins this book with the dark atmosphere and strategy of a murder mystery. Discussing his grandfather he says,

His singular achievements saved countless lives and earned universal praise – until that summer day of horror and shame I was never meant to know about; the day that explained why the memory of such a man could be erased; the day that finally explained his son, my father, to me. (2)

While I was intrigued by this introduction, the danger of this approach is that we may expect a simple solution at the end. I won’t reveal Fitzgerald’s discovery, but as you may expect, it does not tidily explain everything in this family story. This mystery is the carrot the reader pursues through the book, but, of course, there is much more to the story than that. And frankly I’m not sure that this motivation is necessary, when the story itself has so much interest.

Fitzgerald provides a fascinating account of health care in Canada in the first half of the 20th century. He retrieves the story of his grandfather Gerald’s influence in preventative medicine, vaccinations, and the treatment of diabetes. The history of public health in Canada is not only more interesting than you might expect, but it should be required reading to explain some fundamental differences between health care here and in the United States. What Disturbs Our Blood illustrates how the trajectory and shape of a system can be influenced by the altruism of a few individuals. Fitzgerald also saves us from the dry textbook account of Banting and Best we yawned over in school and adds some of the drama of the real story where Banting punches out a junior researcher who threatens to apply for a patent on insulin. These details give us a better picture of his grandfather and point to the tragic irony of insulin shock being used in Gerald’s depression.

James Fitzgerald both recovers forgotten accomplishments of his father and grandfather’s and he gives some broader background that gives context to their midlife plunges into despair. Fitzgerald describes his great-uncle Sidney who “feels the shame and terror his culture attaches to the open expression of masculine fragility.”(311) In the Fitzgerald family and their subculture of Toronto society, men were only allowed to display strength and competence, not vulnerability or fallibility. Once cracks appeared in the hero-façade of his relatives, no one knew what to do with them. They were quickly isolated and marginalized. Fitzgerald salvages a narrative that had been repressed, because the family considered discussion of them, especially of his grandfather, to be taboo.

Fitzgerald also explores the battle going on in psychiatry in the first half of the 20th century between the new “talking cure” of psychoanalysis and the old paradigm of the medical model of disease and cure in mental health. Today when both approaches are often intertwined, we may forget the hostility that first greeted Freud’s ideas. Since dramatic success had been found for the use of chemicals in some diseases with psychiatric symptoms, like syphilis, the hope was that chemicals would be the answer to all mental illness. This change in the theory of psychiatry plays out in the generations of Fitzgerald’s. The first two generations are subjected to all the medical interventions of their day, without much success. Fitzgerald, the author, turns to psychoanalysis which leads to some fascinating writing and hopefully a more successful individual outcome.

As a son, grandson, Torontonian and Canadian, Fitzgerald has redeemed many pasts in What Disturbs Our Blood. While it is a personal journey, which he no doubt needed to take for himself, his inclusion of the broader history enriches his story. I hope he has the courage to continue in further personal explorations and allows us to come along for the ride.

This review appears in FreeFall Volume XXI Number 2.