Shelley McAneeley, B.A., M. Arch.

Shelley McAneeley, B.A., M. Arch.

A review of

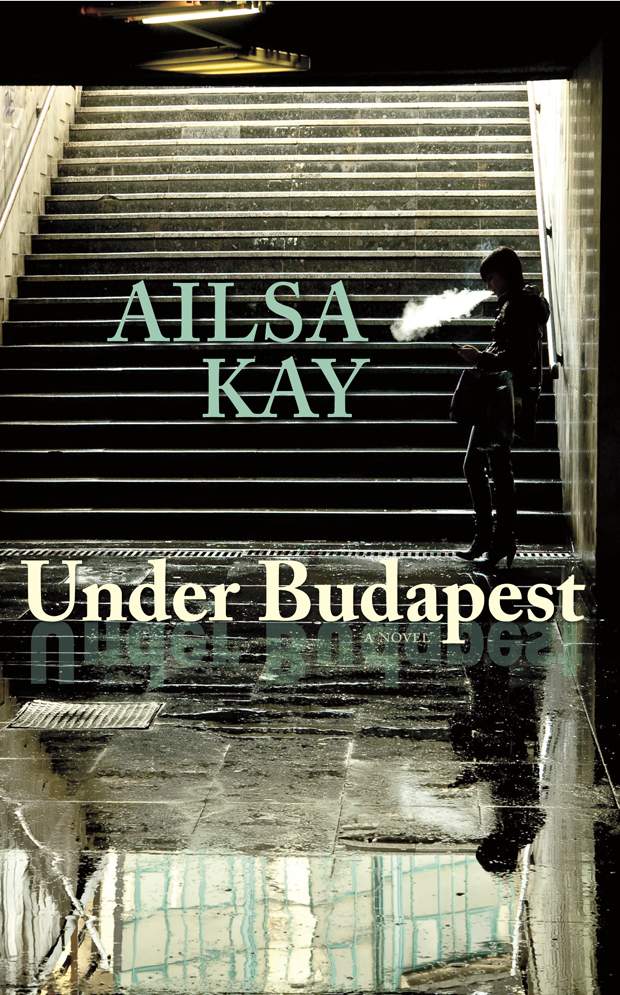

Under Budapest

By Ailsa Kay

Goose Lane Editions

ISBN 978-0-86492-681-4

$19.95

How does a man become a monster? That is, besides the obvious Frankenstein answer with necrophilia implications and a steady surgical hand, idealism, deep love, and political interest all sound innocent, compassionate and harmless, until cunningly withheld, and the human spirit breaks. Observing the transformation of one of the main characters who changes his name to Gombas, a name that sends chills of fear through the city, who, when his heart is deadened by the viscous political regime, and who, when all hope for his lover is gone, transfigures into a monster:

Why gild when there is no sun? They don’t turn the light on for me anymore. Murderers don’t get light, they say. I tell them I don’t need it. My name is Gombas now. Like a mushroom, a fungus, I thrive in the dark and some days the difference between dead and buried is inconsequential (219).

The warp and weft of Kay’s story digs deep and pulls up fetid sores from the past. She spins time into a blur, and space into a non-dimensional heartbeat. Gombas becomes an Hieronymus Bosch chimera. Half-man and half-monster hewn together through personal and cultural history, her main character emerge anew:

The Garden of Earthly Delights in the Museo del Prado

Just two weeks ago, they would have been the ones hiding or running for their lives and this shows on their faces – their satisfaction, happy to be on the winning side again. Revolution over, Gyula, too, is once again exactly what he’d always been: a skinny, bookish man with the hands of a pianist, not a fighter. One punch to the gut knocks the air out of him before he can straighten. He crumples forward. Don’t go down. The next one smashes into his cheek, and his shoulder lands on frozen ground. The toe of a boot meets his kidneys. The grunt of pain comes from outside him. Who else is being beaten in this stone-cold yard? Christ. He prays. No one to save him. There was never any other ending, and they all know it’s only what he deserves. Another kick, this time to the hand protecting his skull. Fingers splinter. He screams. A boot readies itself above his knee. Zsofi (191).

The journey begins with the political idealism of the 1970’s, which appears to be inspired by the Solidarity movement in Poland and the Vietnam protests in the US. Exuberant youth holds high hope for peaceful and nonviolent resolutions to political heavy handedness. The crushing power of the reigning regimes and the surprise of the failure of peaceful demonstrations moved me to sympathize with the newly forming monster. It is not just a personal defeat. Love, peace and all of the idealism defended by youth teeter while the outcome plays out. Good and evil ply against each other in their ever-present duality. The journey of one ideal man unfolds in the grip of hate, war, and violence. Like the paintings of Bosch, these two worlds only exist because of one another, one under the other, whose layers implicate ascension, while the heart of Kay’s protagonist is transformed darkly, unknowably and untouchably.

In addition to the political idealism, Kay layers her story with an innocent love triad. Crushed by love lost and misunderstood, one lover moves on with life while the other becomes enmeshed in a search so desperate, sanity is lost. Paralyzed by desire and caught in the stasis of that desire, love tortures the heart and mind and as if one becomes unconscious only a dark hole remains where once there was a harmonious pulsing blush of red. There can be no going back no matter how deeply one digs:

Gyula’s spade hits rock. Get under, thrust it out. Soil crumbles. Should be flooded down here, but it’s not. It’s dry. It’s dry because it has a roof and walls and they’re waterproof. So the tunnel is waterproof. He’s sweating. Take the coat off. That woman upstairs is finally quiet, her yapping and pounding done. It takes time for people to accept their fates, and then they do and there’s just silence (255).

The hidden life underground in Budapest creates an intriguing setting. What is happening beneath the niceties we see? What is the distant noise and where do those who disappear go. Perhaps underground, both literally and figuratively. Innocent or not anyone can become the target of tortured desire and earn a disengaged heart:

Agi’s mother had always claimed there was a city down here, an insane negative of the world above, where her husband (against all odds) survived. Guyula pitied the woman for her irrational fantasies, pitied Agi for having such a mother, “She can’t bear the truth,” he soothed, stroking Agi’s check (197).

The symbiosis of past and present, good and evil, man and monster created by Kay provides a truly intriguing story with deep meaning. Gawking at the chimera of Kay’s story is unavoidable. I found it difficult to put the book down even though I wanted to. Kay explores the dark side of life that rises from the paradoxical tension. Accolades to Kay for a truly great story

Exclusive FreeFall blog content! For more information about FreeFall Magazine check out our website.

Thank you for reading, Shelley, and for your thoughtful review. I’m interested that you focus on the Gyula character. He’s so important to me, but not to all readers. To me, he’s the mystery that we can never know, the (necessary) hole in the plot which affects everything around it.