Sabrina Uswak

Sabrina Uswak

a review of

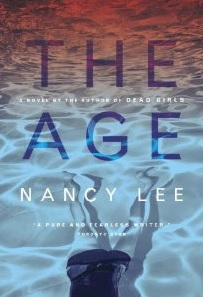

The Age

by Nancy Lee

McLelland & Stewart (2014)

ISBN: 978-0-7710-5252-1

$22.95

Nancy Lee creates an astonishing teen-self-discovery story in her debut novel The Age. Set in Vancouver in the auspicious year of 1984, the novel centres around Gerry and her group of rebellious friends planning to set off an explosive during an upcoming peace march. Lee’s prose is polished and lancing. I was enthralled from the very beginning, completely beguiled by Gerry: a teenaged voice I found to be utterly unique. She is a mixture of the usual cynicism and restlessness of youth, but she has an edge, a sexual yearning and depth of heart that exempts her from being predictable. She is not afraid of the usual things, “of the dark” (12). She fears “dying a virgin, of the new virus, detonators and plutonium, warships in the Persian Gulf…She is afraid of generals and admirals, and old white presidents. Of seeing her father, and never seeing him, of radiation sickness, and reincarnation, being vaporized only to return to an annihilated world” (12). Gerry is bruised from her father’s chosen absence; prickly with her mother and her mother’s newest boyfriend. She wonders at girls, leers at men. She wants to watch the news instead of game shows. She shaves her head without so much as a shrug or defiant justification. She hopes her role in the peace protest will be remembered by the news as “that she came from a broken home[;] a phrase she hopes will lodge itself inside her father” (42).

The Age is deceptive in its scope. There is at once, a political landscape threatening nuclear warfare that influences the tone in the work. Descriptions are unapologetic, visceral. The very first line in the novel destabilizes the image of a sunset, creating an unease that permeates the rest of the work: “The day goes down in fire. Sooty clouds crush the sun to a red stain at the horizon” (1). There are harrowing chapters interspersing the main narrative, following two strangers, a boy and girl, who band together to survive after a nuclear bomb is in fact, dropped. Gerry’s activist friends give convincing speeches about grand ideas to justify why setting off an explosive (just to create smoke and break glass) will finally make the politicians listen. A plan, in hindsight, Gerry knows “the news will get it all wrong” (42), and that will have tragic consequences beyond what any of the group members expect.

The novel’s bones, however, are the nuanced relationships between friends, family and lovers in extraordinary and mundane circumstances. Gerry is troubled by her feelings toward Ian, her close childhood friend. Their friendship is turbulent, clouded by hormones and an inexplicable bitterness and distance. There is a poignant moment where Gerry realizes, “[f]or the first time, she…will not know [Ian] for the rest of life. The truth carries an unexpected sadness” (45). The novel is also as much about an estranged mother and daughter, unable to communicate to one another since the father left. And thus, it is also as much about a missing father. At its heart, The Age explores the fault lines left by trauma. It does not flinch from questioning the motivation to live despite staggering evidence demanding one stay kneeled. I felt altered after finishing this book and sincerely look forward to reading more work from Nancy Lee.

Exclusive FreeFall blog content! For more information about FreeFall Magazine check out our website.