gillian harding-russell

gillian harding-russell

a review of

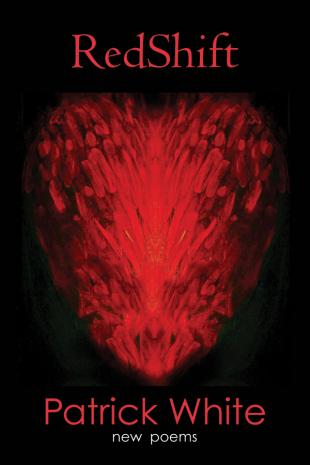

Redshift

By Patrick White

Ekstasis, 2013.

ISBN: 978 1771710275

$24.00

In Redshift, Patrick White attempts epic proportions while his speaker reflects on the human drama against a cosmic backdrop. Interweaving fields of imagery that range from Greek mythology and astronomy to biology and neurology lends a grandeur to poems full of rhapsody, despair, or humour as they consider the human condition. Drawing on Prometheus as the mythic over-reacher who steals fire from the gods to assist mankind, White’s view is experiential and existential. With metaphors that shift planes from one verse to the next, there is a tortuous quality to his poetry that reflects some life-threatening situation with heightened awareness and often angst.

In the first poem, “A good day to enjoy being lost, adrift,” (9) the existential tenor feels almost hearty. A spider web image employs imagery drawn from biology that mirrors similar fields of imagery in neurology and astronomy:

It didn’t take me long to learn by living me

to be afraid of everyone else. That every moment of life

was death-defying in extremis, a highwire act

on a spinal cord stretched like a single filament of a spider-web

between one abyss and the next. (9)

Ordinary life has required a dare-devil attitude for the speaker to survive. He concludes that he must respect others for the same bravery that must be required of them to meet life’s challenges. Far from setting himself apart in this charged relationship with life, White in “I don’t care if you remember me or not” tells the reader that he does not concern himself about fame, and laments in death only that he will find himself separated from humanity and, hence, alone:

There are gaps, there are voids and abysses,

there are neuronic synapses, godheads, bardo states

and black holes we all have to bridge sooner or later.

Love’s one of them. Death’s another. And life’s

a country road with so many potholes it’s shell-shocked. (74)

A shift from cosmic abyss to pothole marks one of these changes in metaphoric plane characteristic of White’s verse. We notice how these shifts have the effect of taking one on a mind journey in which one feels as if one has entered a clearing where a new perspective is offered on what has been said before.

In “The highs are fewer as I’ve grown,” (96) White talks about revelation. His interest in the mind’s surprises while applying his poetic techniques of shifting metaphors and enjambment captures the experience of discovery:

I’ve always been intrigued by the mystery

of the way the mindstream bends like a wavelength

around the corner of its own going

and what seemingly appears out of nothing

like poppies full of dreams in the blood. (96)

Again, an image from neurology finds common-ground in one drawn from physics, and we sense a grand panorama unfolding in one’s mind. Like Dylan Thomas, White draws metaphors out of disparate fields of imagery to create resonant impressions (that transcend the individual images used to create the impression), and thus, he puts meaning through twists and turns to arrive at evolved ways of seeing.

In keeping with the experiential and existential stance elsewhere in Redshift, pain becomes an incentive for creativity as in “Eleven seas of awareness in every drop”:

I strum on my spine

like bruised guitar in the corner, trying

to come up with a bridge to the chorus

of a new string theory that might help explainwhy I act so much like a cosmic membrane

with a broken ear drum. (105)

“Creatively playing in agony” (105), the speaker employs imagery as intricate as it is sinister in its convolution (reminding the reader of the “spider web” (9) across the cosmos in the first poem). Throughout Redshift, a sense of despondency and despair is not unmitigated by humour as the playful and ironic juxtaposition of the “broken ear drum” (105) analogy in relation to the more grandiose astronomical “string theory” suggest. Nevertheless, in only one poem in the collection do I sense the speaker’s personal comfort and happiness, and that poem is about a kitten which the speaker adopts from a friend, “My Feral Kitten, Ripple” (107-109). Even this poem, however, reaches beyond its own boundaries to evoke a profound and evocative image relating to the human condition:

If Kafka’s right, we all lie in the lap of a vast intelligence

but it doesn’t pet me the way I stroke you

as if I were first violin in a string band on a streetcorner

playing music on your melodic fur. (109)

Just as pain is an incentive for creativity in “Eleven seas of awareness in every drop” (104-106), despair becomes another kind of inspiration for writing poems in “Come to me in rags of blue fire” (130-131). Here, bathos mixes with pathos as the poet-with self-irony (in identification with the speaker who has lost his faith) invokes the comic image of the “goat whose piety is a broken horn” (131). These imaginative shifts and the originality of the verses dazzle but at the same time leave one a little stunned:

lift him up in the rain above the sphinx in the desert ripe with diamonds,

and let him know, softly remind him, confess and confine him

like a cemetery covered in a keyboard of snow

until he confesses there’s an asylum in the heart of chaos

that sings to itself like an emergency constellation. (131)

Not only does White share Dylan Thomas’s habit of applying freely associated metaphors (whereby he seemingly pulls diverse images out the hat of his subconscious) to create a composite impression, but he also shares with Thomas certain aural effects that lend musicality to his verses.

Redshift is a thick collection of poems (186 pages), well integrated by patterns of imagery and theme, with some of the most striking and unique metaphors that seem born out of some personal and overwhelming struggle. Referring to the astronomical phenomenon of a star appearing red when it retreats from the viewer, ‘redshift’ encapsulates a feeling of life’s retreat after a spectacular (painful and/or full of angst?) fulfilment. Although at times I found the verse difficult while the imagery changes gears too many times for me to absorb their combined significance, and often the lines ran overlong and seem verbose, here is a poet with a charged vision and much to say about what it is to be human and to struggle.

Exclusive FreeFall blog content! For more information about FreeFall Magazine check out our website.