Annie Vigna

Annie Vigna

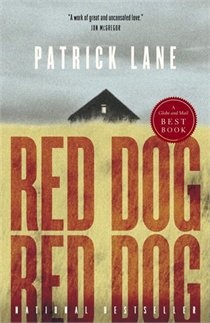

A Review of

Red Dog Red Dog

by Patrick Lane

McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

ISBN 978-0-7710-4632-2

$21.00

“Patrick Lane has always walked the thin ice where truth and terror meet with a kind of savage intuition.” This quotation is taken from The Vancouver Sun and appears on the dust jacket of Lane’s There is a Season (Toronto McClelland & Stewart Ltd. 2004).

The reading of this memoir was my introduction to Patrick Lane, author of more than twenty books of poetry, and recipient of most of Canada’s top literary awards. I was going through an excruciatingly sad time in my personal life, and reading Lane’s stark realities was somehow soothing to my tortured soul. How could that be? It was his writing, his lyricism that transcended the raw truths of his past that he exposed while tending his garden in the present, planting for the future. It was redemptive. And I was hooked on this writer.

Patrick Lane’s first work of fiction Red Dog Red Dog was published in 2008. It is a novel that takes place during a week in the lives of two brothers, Eddy and Tom Stark, young twenty-something men living in a small community in the Okanagan Valley in 1958. And it is about more than this single week—it goes back as far as the 1880s told by the ghost of a younger sister Alice, who lived only six months less nine days.

Father gave me a little charm on a string. He tied it around my neck in the hope it would necklace me to heaven. Instead, it hung me here on earth, my spirit roaming (87).

Lane’s use of an omniscient narrator puts the reader in touch with members of the family tree, their unrelenting grip on the lives of Eddy and Tom. It’s a device that allows the reader to examine the legacy that these young brothers inherit. “The past makes us what we are” (p 3).

Is there any salvation? Look to the title for a clue. Were it not for exceptionally beautiful descriptions of the natural world, it would be difficult to read this dark novel that describes unrelenting violence. This novel records the cycle of procreating, birthing, dying, burying, and burning; the savagery of dog fights; the antsy desperation of a heroin addict needing a fix; and the alcohol or drug-induced calamities of the dysfunctional Stark family.

Elmer and Lillian Stark’s progeny consists of Eddy, the first born, fiercely loved by his mother, Tom, an after thought, born two years later, and denied maternal love. Then came Rose who lived for only a week; then Alice; and finally unknown “Starry Night”, the burnt offering, born of a different mother, but fathered by Elmer Stark.

At age fourteen, Eddy is caught drinking whiskey, laughing as he throws coins at drunks in the park the day after he and his buddy Harry had broken into the bar in the Legion, stealing liquor and cash. Harry manages to disappear into the crowd, but Eddy is apprehended by Sergeant Stanley and sent away to Boyco, a correctional school for boys in Vancouver. This is the event that starts the downward spiral in Eddy’s life and, indeed, the lives of the entire family.

There was something dead in Eddy’s head when he came back from the coast. The boy he’d been was no longer there, and in his place was someone gone past feeling, who thought nothing of pain, his own or anyone else’s.

Even Father stepped sideways when Eddy walked behind him (18-19).

Eight years later, stoned on heroin, Eddy carries out his plan for retribution against Sergeant Stanley by setting his shed on fire, and days later, poisoning his beloved German shepherd.

So what if he’d been throwing money and laughing at the drunks scrambling in the gutter for coins? But it wasn’t just being sent to the coast, it was the three days before he was put on the train, his two nights in the cells. Stanley was worse than the guards and older boys in Boyco. Twenty-two years old now and he had never stopped living what happened (20).

In contrast to damaged Eddy is Tom. Tom, bereft of maternal love and devotion, somehow instinctively avoids the traps and temptations to which Eddy succumbs. Tom is the good brother, but not entirely untouched by his sense of justice to right the wrong. There is a gnawing, unconsoled hurt from his childhood that just won’t surface, and Eddy tells him not to remember.

It was Eddy who told him that everything would be okay, and not to think, and never to remember. But he had remembered . . . (319).

Here’s the salvation:

And he tried to understand, because now, right now, none of it seemed to matter (319).

Redemption!

If you want to meet some memorable characters, experience life on the edge, and delight in astounding descriptions of nature, then be prepared to be overwhelmed by Patrick Lane’s Red Dog Red Dog.

This review first appeared in FreeFall Volume XX Number 2.