By Tonya Lailey

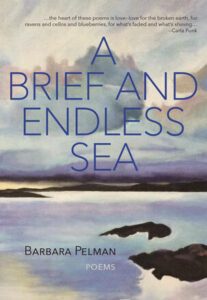

A Brief and Endless Sea

by Barbara Pelman

Caitlin Press (2023)

The poems in A Brief and Endless Sea, Barbara Pelman’s fifth book of poetry, address a lifetime of lovers, loves, and losses with vitality and a piercing presence. Pleasure and beauty gather at every milestone. Not avoidant of danger and pain, these poems name the difficulties without dwelling on them. Pelman punches holes in darkness where she can.

The book of poems opens with “Now Is the Time to Light It”, a six-stanza cento based on lines from Patrick Lane poems and dedicated to Lane. The dedication includes “z’l”, an expression in Judaism to express “may his death be a blessing”. The fourth stanza reads:

Touch their lips with your wings so they may sing,

Be with them what the heart is when it sleeps,

Cleanse the dark and let the dead have blessing.

If, after this, there were doubt as to the spirit in which this book was written, the Ingmar Bergman epigraph drives it home: It is necessary and not at all shameful / to take pleasure in the little world.

The first section thrums with youthful, sexy energy. The speaker awakens past lovers with sensual force. In “Cello”, the camera work is close — his lustrous skin, his eyes solemn, so liquid / he filled me up. In “Notre Dame” (particularly poignant given the fire in April of 2019), the speaker recounts the boy with sad green eyes, the boy with whom she gazed at the gargoyles of the famed church. There’s a gorgeous conflation of building with human body— the architecture of touch tumbling into confusion and illumination with the features of the iconic Gothic French house of worship….I remember the scarf, the way the breeze / lifts his hair. But I miss the arches, the beams. / My head on his shoulder, I can’t see the frieze / or the stained-glass window.

“Blueberries,” a glosa, owes its borrowed lines to Laura Apol’s poem of the same title. In the space of the four, ten-line stanzas, the small blue fruits are infused with desire. A pleasing series of “ifs” precedes a final afternoon delight, suggesting that the delicious union might not have happened had the day itself and the field not conspired to make it so…

We fed each other blueberries, one

at a time, our lips blue, our teeth blue,

his fingers in my hair, blue. Blue

slid into our mouths. Blueberries,

acres of them, ripe for picking.

In other poems, Pelman’s sharp sense of humour is a gratifying counterpoint to the heady sensuality.

First Time

Jericho Beach, 1960This moment was to change me

from girl to woman. As splendid

as sunrise. As beautifulas Beethoven. Ode to Joy.

What it was: sand under my thighs,

girdle twisted around one ankle.You should wash yourself out

when you get home, he said,

you know, a douche.

The girl we meet in “First Time” has become a woman in, “Wild a Little While”. She’s in London. It’s summer. So why not get off the bus with the young man? Why not then take the stairs to his flat…And the sun rose and fell, / somewhere else. It was day, / it was night. We ate on the bed, / or did we eat anything at all?

The book sails backwards past youth and lovers to Pelman’s ancestry, to the origin of her surname. A mishearing of Puidelman? Or a cold disinterest in the specific sounds within the waves of people arriving to this officer’s desk on Ellis Island.

Though the dropped letters in the surname are gone for good, along with the babushkas, the samovar sold for pass money, the people are in these pages —grandmothers / who also sat, looking primly out a window / to another country , and the speaker’s own mother and father. We meet the parents as a loving couple and in intimate moments as individuals with their daughter. We meet them, too, in their respective illnesses and advanced age—And Father, early spring on your white hair, / What are you doing, dying?

Love does its work in these poems, lets the speaker speak her mind about how hard loving can be. This is especially true in, “Trying to Hold My Tongue” where the couplet form embodies the tension between mother and daughter, a charge that builds toward a final potent line…

When I walk with her she tells me

that the cars on the street should be in garages,the city should fix the sidewalks,

the neighbour stole her newspaperthe helper stole her keys,

or her wedding ring, her earrings,that I should wear some lipstick,

my grandson get a haircut.I am ashamed to write this. Other people

are tender to their mothers, grieve their passing.I fear my mother will outlive me. I will one day

short all the circuits in my body, die in electric rage.

What a gorgeous moment of honesty with an intensity equal to the very different kind of electricity in the first section of poems.

In the third of the book’s six sections, we encounter the speaker as the mother in relationship with her daughter and grandson. “This Is Not About The Grandson” does that wonderful rhetorical trick known as a litotes, claiming it won’t be about something while it goes ahead to address that very thing, thereby adding nuance and complexity. After all, Nobody wants to hear about the time / he threw up his beets, was astonished / at the red he created. They have their own stories, / photos on Instagram, / fridges covered with crayon drawings.

In “Coming and Going” Pelman plainly addresses the longing a mother can have to share in the adult life of her children. The plain-spoken delivery is powerful—never enough words to say to my daughter, / who considers me nosy. Wanting to know / about her life. But the door closes / after I ask: how are you doing? Fine, she says. / Always the desire for more.

Judaism along with Pelman’s own practice within the Jewish faith belongs to the richness and depth of this book.

“Pomegranate”, a poem in numbered sections, digs into the fruit itself, to its abundant storehouse of seeds padded in juicy red flesh – don’t give a damn red, rubies red. / That red.

After the playful Rhett Butler/Scarlett O’Hara reference, the poem unfolds into rabbinical teachings, stories full of vibrant imagery. The rabbis suggest that the tree / in the middle of the Garden was not / an apple but a pomegranate. How much longer / a time from ignorance to knowledge, / from innocence to sin. Time to contemplate / this seminal action. Eve sitting down in the grass, / struggling to cut through the thick skin, / soon covered in pomegranate blood…

There’s great movement between near and far in this poem, a satisfying ranginess – the fruit at hand and the symbolic fruit of history, religion. The speaker’s fingers mistype the word pomegranate. Other words are brought to her mouth and to the mouth of her grandson: Raven. Hawthorn. Oregon junco. A beautiful music pours from the paradise red seeds.

The energy ebbs in the later sections of the book which can be felt as a slowing/softening into the embrace of age, a theme in these later poems, but can also feel repetitive and complacent when compared to the juicy sensuality in the leading poems.

The theme of nothing lasts, for example, might not have needed as many verses. This stanza alone, from “Fragility” does a stellar job…

Flowers everywhere,

every vase filled.

Daffodils from the garden,

tulips from the florist.

Such a short time

of yellow.

“Feast On Your Life” could be the title of this collection. It’s the name of the penultimate poem in the book, a glosa, a form Pelman clearly loves and has mastered. This glosa owes its four borrowed lines to Derek Walcott’s poem, “Love After Love”. The title comes from the final line of the same Walcott poem. And what tenderness to arrive at before the final poem, “How To Leave This Good Earth”. In “Feast On Your Life” Pelman reminds us that the act of loving is the ongoing feast, loving the daughter, / the grandson, the ancient mother, / the tomatoes in the garden, the cat / strolling across the yard, curling / onto the chair you sat on, the last morning / of sunlight…. And, of course, as the final stanza concludes, the feast that is loving oneself.

Tonya Lailey (she/her) writes poetry and essays. Her first full-length collection, Farm: Lot 23, was released this year by Gaspereau Press. Her poem, The Bottle Depot was shortlisted for Arc Poetry 2024 “Poem of the Year”. She holds an MFA in creative writing from UBC.