By Beth Everest

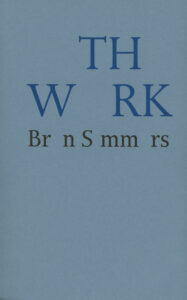

The Work

by Bren Simmers

Gaspereau Press (2024)

Even the construction of the cover page predicates a main theme of Bren Simmers’ fifth book, The Work. The vowels in the title and the author’s name are curiously embossed only enough into the paper that the reader is drawn to see between the consonants. While one might, at first, think this to be a publisher’s gimmick, the receding letters suggest the predominant story in this well-constructed book.

The poem “Load upon load” in the book’s first section “The Work,” reveals the tension:

…Only in the

quiet drunken hours

can he let go. And now

you’re gonea streetlight flickering

on and off that he talks

to like a Ouija board.Yes or no.

The pain pooling

Under the surface… (15-16)

The image with the Ouija board suggests movement that could go one way or the other, the fine line between mystery and belief, the unpredictability of life and death. Pain and loss swirl under the surface in this book, pain from cancer diagnosis and subsequent death of a sister-in-law, pain from grief, abandonment of a father, advancing dementia of a mother, and turmoil and guilt of the caregivers. What decisions can be made if there is any choice at all? And would choice make any difference. Is this a depressing book? No. It is a tender and empathetic view of what is real. Very real.

Clearly, as Simmers says, “these are extensional times” (19). Extensional is a curious neologism. Essential? Existential? Extended? Extension? Tension? Exception? Existence? It seems to mean all of these and more. I’ve cherry-picked a few lines over 3 pages as example:

“Deep /listening looks like doing /nothing…houses flipped / all around and me wanting / to slow down” (19). And then “Whose definition of ‘essential’/ sees our choices as exceptional / Am I talking to myself again/in the plural? How to navigate / self-loathing with only icicles / and moon halos for compass (20)….Please / let me lie beside my love / and sleep like a bulb / until spring (21).

These pages vividly show the poet’s extensional, a composite of emotion and anxiety when one is overwhelmed. Particularly poignant is the image of “sleep like a bulb.” In fact, much of the imagery in Simmers’ book warrants a closer look.

Another poem that particularly demonstrates the artistry of movement of the images is “Ice Fishing.” Here the poet tells a memory of the father who taught the speaker to “cut a hole in ice with an auger” and wait for the fish “No hook, no bait” until “they leap, gasping, / flopping at my feet.” Because we already know something from the previous poems about the relationships, this leads up to the final very moving lines of this piece:

These days,

I don’t need a shelter oran opening to talk to him.

Simply stand on the ice

let the wind scale

my cheeks” (30).

It’s lovely. The play between image and form are strong components of the book. While most of the lines in the “The Work” are quite short, “Fork Gospel,” the third section of the book, plays with columns that can be read as lines across the page or down through the columns. Emphasis changes either way. Take the beginning of “Lying in bed at the end of the

world” as an example:

Late August, It will continue

the hour of sleep to worsen. Talking

won’t come the tug between

the last ice shelf what can we do

calved, Greenland, and the inevitable.

a cube melting Wanting to spend

in a whisky glass, these dogeared days

the government… growing cucumbers…(29)

This clever inter-positionality of the line more than doubles the feeling of the angst and grief expressed in the poem. “What can we do/calved” because there is nothing that can be done…except, perhaps, “wanting to spend/in a whisky glass.” Later in the book, in “Fork Gospel Triptych” (33), Simmers uses a similar technique but with 3 columns that make the thoughts come across as much more anxiously punctuated.

Perhaps, though, it is in the third section, “Still Mom,” that these elements really come together. Not only do the poems lose more of the vowel o, and in many cases, the o is simply absent. But as the Mom takes to writing more sticky notes to paste on the walls, and the dementia becomes more aggressive, and there is more looping of thought, the letters of the poems spread across the page with greater spaces in between. The impact on the reader is curious. Instead of thinking, yes, I’ve seen this before, I wanted to lean in, to hear more, to understand, to listen more closely, to hear those moments when Mom is more clear-headed, more connected to the world outside of her head:

it’s so good to talk to you like looking into a wind w

that’s usually drawn and seeing y u inside, still

m m (51)

I felt those moments, the sensitivity, the very real. And the final lines of the last poem in that

section, “My M ther’s Sweater” (54).

can’t bear t wash r wear it

since draped ver the back

f a chair a reminder f

her perfect stitches that nce

mended my h les

Beth Everest enjoys the freedom to write, to create jewelry, and to dig carrots in her own garden. She is fortunate to publish in journals across the country, and occasionally come out with a book.