By Catherine Owen

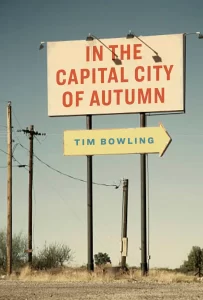

In The Capital City of Autumn

by Tim Bowling

Wolsak & Wynn (2024)

Tim Bowling’s body of work holds the distinction of being both diverse and consistent and his latest book is no exception, showcasing his willingness to delve into new territories, such as pieces in the voices of the minor characters in The Great Gatsby, along with his determination to preserve an alliance with the essential nostalgic in his poems on his family, salmon fishing and elegies for a deceased dog. Although Bowling has lived in the prairies for several decades now, his memories of a West Coast childhood on the Fraser River persist most thoroughly as core subject matter in his many books. The five sections of poems here, however, often take this basic anchor and render it surreal, more a haunting, a core mystery, than merely a recounting of the past. Witness the salmon now pressing their “silent laughter to the cracked/linoleum” (Apprentice), the “single nailhead of a risen seal” (In Ladner Harbour) or the “dandelion’s floating sperm” (Ancestry). The melancholic tone of mid-life permeates Bowling’s always-precise acts of sight as the “first girl” he loved drifts through, children grow; he sees other’s faces “as old as mine” (In the Beginning) as he morphs into the watcher rather than doer, a contemplative “memory of self” (Cherry Blossoms).

Whether the section on Gatsby or pieces of greater levity such as “Report Card for Middle Age,” where the speaker’s attitude and hygiene is marked as “Needs Improvement” or his “Found Poem of Strait of Georgia Insults” that see the names of fish twisted into Shakespearean disses like “Surf scoter” or “Sea-clown triopha” are necessary injections of less-ponderous material or distractions from the potentially-darker lyrics is up to each reader and what they think they need from poetry in the moment: intense emotional entrances or a range of tones and tales. The titular poem is especially powerful as it repeats the line, “In the Capital City of Autumn” in stanzas that embed moving slant rhymes such as “pear/here,” and “thief/sleep” along with syllabically-varied rhymes such as “scarecrows/snow” to draw a potent picture of middle age that pulses with dream imagery inflected by poets like Neruda, Stevens, and Vallejo. Goldfish “from bowls that shatter in transit over bodies of water” or “the moon’s an egg in the pocket of a running thief” combine surreal visions with delectable assonance, enabling Bowling to etch stark and generous fables in our minds. Those of us who survive to mid-life can access the bittersweet tonalities, while the imagery takes us beyond basic saying into a reverie of beauty and strangeness that lingers. The final part on Bowling’s dead dog could have collapsed into sentimentality, but, mostly, it doesn’t. Who else could close a poem with the couplet, “I stand like an open wound against the sky/The joy’s here. I’m awash in it, bone dry” (Returning Home) and let it remain with all its complex empathy within the evening of our lives.

Catherine Owen, a Vancouverite-Edmontonian, is the author of sixteen collections of poetry and prose. Her most recent book is Moving to Delilah (Freehand Books 2024) and she has work forthcoming in Ampersand, Queen’s Quarterly, LRC and The Best Canadian Poetry 2025.