By Tonya Lailey

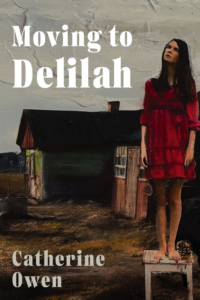

Moving to Delilah

by Catherine Owen

Freehand Books (2024)

I just walked in, beneath the simple lintel,

and the walls spoke in a definite whisper,

“My name is “Delilah” and there was no doubt. (The Voice, p. 14)

It’s with this tender authority and pinpoint intimacy that Catherine Owen invites the reader into her seventeenth book and most recent collection of poetry, “Moving to Delilah”. And like the best kitchens in the coziest homes, it’s easy and gratifying to stay here, steeped in the rich detail of a courageous and creative life.

To get to Delilah, her new/old house in Edmonton, Owen must leave Vancouver, the ocean, the place she has grieved the loss of her spouse to addiction, the subject of her previous poetry collection, “Riven” (a misFit book, 2020).

The opening poems in “Moving to Delilah” make room in the word home for the past and present to live together, challenging the compartments of the mind with truths felt in the body…we were heading to Clearwater, a halfway point / with two cats, everything I owned, except for all I had lost.

We enter Owen’s childhood home through the poem, “Two Homes: a corona”. This is the home that shaped, for her, the meaning of home, cultivated a feeling for needing one of her own, to live in the seeming-magic of what was. With grace and alertness to crumbs, Owen sweeps her childhood kitchen into Delilah’s where it retains the core feeling of gathering space, painted / ochre, teal and sea foam to replicate the coast or some exotic / realm of warmth. The corona concludes with an embrace of home as a nourishing psychic space — a consolation, / a solace, if never a turning back of youth’s clock, still / the hope that your dreaming has its parts, chapters, / a form that turns a chaotic story calmer though / your childhood home sings (always) in your blood.

In “Delilah”, that begins the section “House”, the speaker addresses her dead spouse, [y]ou wanted me to have this house and I always / listen to the dead… Again, the past, the dead, are welcomed here. Owen treats Delilah, her Salt Box house, with the fullness of interest she brings to her own life—with deference to history, with curiosity. She digs into the local archives as if to affirm that the true passage into her new/old home is through a portal fixed to the outset of the last century … Since 1905, when there was nothing else / around it, just grass and saplings in aching / distance from the river, how many lived / in this place…

A series of well-honed haibun expose the material accumulation of lives lived in Delilah, like an artfully partitioned excavation site. To the building permit found with none of its contractor boxes ticked, Owen replies: How much we rely / On the writing in the sand / Near a hungry sea. For the long-coveted wallet of a Paul Deran, relinquished by the dismantling of the aged garage roof, Owen has these words: Identity cards, / photos of a beloved: / Life’s tiny wallet.

“The Pipe” must be the most beautiful plumbing poem ever written. The rot? They call it blossoms. // Rust in small dangerous buds on the eroded surface, promising / to split, flower into a disaster of flood. // Is there anything we can do to stop it? Replace segments, / understand our history, hope the bouquet never assembles.

Like an all-round gymnast, Owen leaps between poetic forms with grace and seeming ease – pantoum, corona, sestina, sonnet, abecedarian, each form in humble service to the content, its apparatus undistracting. There are couplets too, a recipe, list poems and various innovations: A series of “Tally” poems to account for garden bounty – and paucity – in summer months; a collection of tiny love letters sprung from Edmonton Journal headlines. The seasons on the land and within the writer return and return as salient themes – That winter is a place you will relearn every year, without guile and without gumption. (Forms of Knowledge: Winter, p.63).

“Postcards from the Archives, 1905”, replies to the longhand of brief correspondences, some of which may never have landed an answer in their own era. Gertie, where is she on this close, / sky-breaking evening, this culmination / of humidity, a clash and then that / hum of aftermath and again / when when when. Owen’s responses are emotionally keen and thoughtful. Her questions quiver with the sweet charge one gets on receiving this now rare and pithy form of mail. How are you, you ask, but there is too much // wilderness around it and where’s the love / outside this dark postcard – who’s still in the parlour / and who’s in the mire, who’s sipping tea…?

The collection steps from the house into the garden. Here the seasons fall out of order. The reader is free to discover each poem without the pretense of it belonging to an expected unfolding. The garden feels spacious and at a remove from the gardener in a respectful way. What surfaces is Owen’s wonder at the garden’s own bustle – that teeming, incessant, intricate lifework. Owen will come to cultivate this adopted garden as her own. That first May, though, she will have to wait for someone else’s dream, engage in a green guessing game.

We’re introduced to some of the characters who visit Owen’s book box and to the weather-beatings the box takes and recovers from through upgrades and repairs. Owen insists on book box rather than small library since library books need to be returned and the book box has no such limitation. At one point we’re crouched in the bushes with the speaker, overhearing the book-box chatter, coming out of hiding to receive some unexpected appreciation for the box and for the way Owen has curated its content.

The garden is heady in peonies, sunflowers, in green tomatoes that stay green or get missed to become ripe beneath / the branching flow of nasturtiums and old peonies. Browned crab apples regain their vibrancy in a 100-year-old muffin recipe. In “Eternal Recurrence”, sparrows feed on sunflower seeds in winter, become the gears in an eternal clock’s mechanism. Sunflowers raise their heads again and again. In “Sunflower, August”, they claim their end-of-season grandeur: The mammoth is its own planet. Owen gives a long overdue tribute (in the poetry world and beyond) to the ant that checks on the seams of the peony. The tiny creature has clearly been up to something sacred all along. We see it as sentry or pacer, useless perambulator, / but it’s precise, patterned, devotee.

Out past the garden, in the neighbourhood, cherished small businesses hang on for dear life with a bit of luck and a lot of love, a love apparent in “Five Business between 118th Ave and Little Italy”. In “Pink Polish Nail Salon”, None of them have names we know in that soft / Vietnamese tongue, but their friendliness extends / through the white room with its phalanx of massage /…

At “Fast Shoe Repair”, Gino has retired, finally, to dance, and now Manny from Ghana / has taken over, though he tires already of the cheap, / everyone wanting everything for less… The “Wee Book Inn (shut down in 2020)”, is the exception. So where does the cat now wander and plop? Has someone set its basket beside another till?

In the summer, the neighbourhood at-large rocks hard to Prism, Glass Tiger, Tom Cochrane, to Danko Jones, I Mother Earth and Our Lady Peace. The Classic Rock Fest poem succeeds, through sensual layers, to bleed rock and roll summer festival all over the page – the squealing guitars, urinals, stupidly priced drinks and food, the thick and motley crowd, the sun and the floodlights passing each other on the ways they were going. More than that though, Owen pins down that mix of desire and body surrender that transcends nostalgia, transcends age, recognizable here as the life force maybe we always carry, the one just waiting to be woken up…the music entered me, / not just in a bygone sense but from the now’s need to move – a power in this urge – / time live as its moment’s wires, …

A gorgeous love poem arrives toward the end of the collection, “New Year’s Eve Feast at the Hotel Macdonald, 2018: a sestina for Michael”. The love here is the biggest, widest sort, the sort of love Owen expresses again and again throughout this book. From its opening lines, the poem radiates the stunning beauty and possibility to be found in acceptance, Nine years on and they seats us where he and I had sat, him / a scraggly man with gangly teeth but still, somehow, a beauty / to me, and you so very different, wearing a shirt of blue koi swimming, you, / on this last day of what had been a strange, victorious year, / yes, both hard and hoy, as in the posh salon of couples and blood…

While deeply domestic, this book is not domestic in isolation. The housing crisis, climate change, Covid angst and loss, poverty, homelessness, death, grief, sexism, addiction and the ruthless hunger of the oil and gas industry belong to the book’s broken heart, to its joyful healing and to its generous imagination.

Owen is fully at home in her craft. Her poetry is finely tuned, rich in surprise, densely sonic, pleasingly rhythmic. Her diction is achingly fresh. Jane Jacobs’ wisdom about old buildings comes to mind: “Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must use old buildings.” (The Death and Life of Great American Cities). Owen has already put Delilah to very good use.

Tonya Lailey (she/her) writes poetry and essays. Her first full-length collection, Farm: Lot 23, was released this year by Gaspereau Press. Her poem, The Bottle Depot was shortlisted for Arc Poetry 2024 “Poem of the Year”. She holds an MFA in creative writing from UBC.