By Skylar Kay

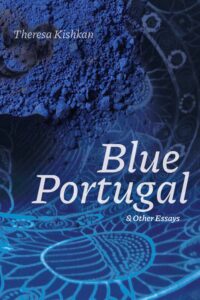

Blue Portugal

Blue Portugal

by Theresa Kishkan

University of Alberta Press (2022)

Blue Portugal, Theresa Kishkan’s new collection of essays, presents life as mosaic. Kishkan stitches and mends together bodies, shelters, and family histories in both Europe and Alberta. She shines a bright light through this mosaic, traces all of the soft details of cities new and old–from riverside shacks in 1918 Drumheller to the cobblestone streets of Czechia and Ukraine. Regardless of location, however, Kishkan is consistently able to guide the reader around a slow meditative meandering circle about an idea or trope, seemingly lackadaisical at first, until diving in an often unexpected direction to piece together what at first glance looks like dislocated stories, events, and people.

The slow circling of the first two essays in Blue Portugal, “A Dark Path” and “Blue Etymologies”, evokes haibun-esque movements–a casual and precise description, and subsequent reflection, of one’s surroundings. Even at the micro level of writing in these two essays, Kishkan’s history as a poet becomes obvious; verbs are strong, and rarely is a word out of place, as strong narrative voice carries a seemingly mundane topic:

What the cloth remembers, I will remember too—gathering the stones, sewing the circles that became the growth rings of larch, tying cotton string as tightly as I could. And the cloth and I will also remember the raucous sound of adolescent pileated woodpeckers finding their wings, learning what a voice sounds like in open air, in the morning, before the heat begins (17).

This precision from the first two essays is something that I feel the final essays lack. For example, in the essay “Blueprints”, Kishkan starts a section with “There was a shop in Brno I passed when I walked from my hotel to the university where I was teaching for a week” (92). The excessive copulae and general weakness of verbs set the tone for an essay bogged down by flat language, contributing to a pacing issue characteristic of the later half of Blue Portugal. While the writing in the first half was precise and Kishkan’s wordcraft was enough to keep my attention during the descriptions of the mundane everyday life, this feeling sometimes wanes in later sections, causing the collection to slightly drag.

Despite these occasionally sluggish sections, I still saw promise in the last two essays–“The River Door” and “Museum of the Multitude Village” which delve into family and provincial history. Some sections remind me of Jordan Abel’s Nishga, as Kishkan makes use of fragmentary maps, old family photos, and unreliable first-hand accounts from the 1910’s to augment her own narrative and piece together a family history. I do wish that Kishkan had done more with the visuals–overlaying and blurring boundaries between the visuals included, and perhaps just more visuals in general. Statements like “In the digital version of the microfilm I was sent by my son in 2016, after I’d discovered the information about the camp and their residence there, I can see tattered pieces of a map but some are missing and I can’t make any sense of it” (148) come and go in text only with no use of a visual, no artistic re-rendering of pieces of history. These omissions just left a few sections, although informative, a little flat and incomplete, unable to hold the attention of readers less invested in Kishkan’s family history–a point even Kishkan concedes: “Everyone is nice to me but I know they don’t understand my urgent need to determine where my grandmother lived, where she lost first one, then a second, and finally a third family member in a short period of time” (146).

Putting aside these blemishes, the collection manages to tell Kishkan’s story—one many can relate to. It is a story of battling injury, keeping family together, uncovering a nearly-lost family history, and everyday acts of creation. Kishkan’s Blue Portugal gives the reader a blueprint for charting and tracking one’s own history through all the highs and lows–a valuable read for anyone tackling autobiography or essays.