by Patrick Connors

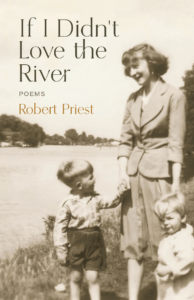

If I Didn’t Love the River

by Robert Priest

ECW Press (2022)

Robert Priest’s latest collection pushes boundaries. It cannot be defined as one school or “type” of poetry. It challenges, educates, and entertains the reader.

The title piece contains lines such as, “If I didn’t wish for the world to thrive/If I didn’t work to change minds/that wouldn’t be love.” Also, “If I didn’t love the scorned, the othered/If I didn’t love the children of war/how could I truly say I love anyone.”

The reader has been introduced to the poetry and person of Priest, if they hadn’t already been before. He gently, lovingly, encourages the reader to pick a side.

The poem, “Depression,” is incredibly courageous and empowering. “…in a maelstrom waves and waves are dashed away/and scattered in the morning’s deranging wrath/Just so my thoughts are shattered by each thought.” Later in the piece, “My currents cross, collide, and disappear/and I am sucked down to the ocean floor.”

The sustained metaphor gets the struggle across without being too heavy-handed, in a manner which can be appreciated by anyone who has ever suffered from depression, whether a fan of poetry or not.

“Sonnet of Many Skins” is a poem requiring some study and reflection. At first, it doesn’t seem to fit the form. However, after some research, I discovered that the rhyme scheme (ababcdcdefefgg) exemplifies several potential variations of a sonnet. Most likely, it is designed to be a Bush Ballad Meter Sonnet – which makes sense, given his songwriting background. Priest may also have intended it to be an English Sonnet, which would be appropriate, given that he was born in England.

There is continuity in the piece between lines which are not part of the same scheme or “stanza” (although there are no breaks). For instance, lines four and five: “A patterned snakeskin of thought torn loose/A frozen skin of cellophane I hide.” Here we again see the world of thought and its importance to the author, but depicted as something which can be shed.

In contrast to the very contemporary comparison of snakeskin with cellophane, the poem ends on a very classical note. “The ancient skin’s three-legged walk, a crutch/of bones to pitch the many-layered tent/in which the poem binds his song to soul/as though life had some single path–some goal.”

I’m not ashamed to admit I had to read this poem a number of times to “get” it, but I loved every single moment.

“You Were There” would seem to be about his long-time wife, Marsha. I make that claim because Priest has a poem in this book called, “My Woman Named Marsha Kirzner Thing,” as well as referring to a poem he had written in a previous collection for her in “I Want to Go Back.”

But, Priest doesn’t personalize in “You Were There,” although he does personify. “You were there/when the stars fell down/and burned my eyes.” Later on, “And when I got anywhere/it was like you had preceded me/It was like you had always been there/Awaiting my arrival.”

Here we see love as the unification of all things, told in a way which is universal. The reader can infer from this their own love, as long as it is true.

Throughout the book, Priest blends politics and love, formalist work with free verse, and Romanticism with post-modernism. There is something in there for old and new fans of his work, and he gets his message across with much musicality and little proselytizing.

Patrick Connors is the author of The Other Life, published by Mosaic Press. His book reviews have been published by entities such as Canadian Stories magazine, and the League of Canadian Poets.