By Beth Everest

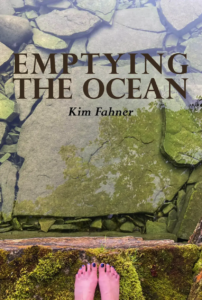

Emptying the Ocean

by Kim Fahner

Frontenac House (2022)

Because the title, itself, of Kim Fahner’s latest book suggests the impossible, I am instantly intrigued, and Emptying the Ocean does not disappoint. I find myself floating somewhere between that ethereal quality of myth, and stung by the very real sense of longing, loneliness, fear and grief. There is a journey here, one that takes the reader through Water, Earth, Air and Fire, which divide the book into sections, but Fahner adds The Spiritual and a return Homewards.

In the opening section, Water, icebergs form particularly poignant images:

Edges of ice aren’t sharp

except from a distance (12)

…

She walks down to the sea, hears ice whisper:

The sea speaks Selkie,

the whole song echoes

Then—

sings her own song.

Edges of ice aren’t sharp,

so sculpted by sea—traces,

curves, caresses what is

both seen and unseen,

along this body, her coastline. (14)

Throughout the book, Fahner reminds us to look more closely, that not all is what it seems, that what we see/hear from a distance is only one perspective, that there are Selkies and other mythological figures, other shape-shifting artists, and the elements that change/shapeshift. Deliver. The readers’ own journeys can’t help but be brought into the equation.

Also captivating is the poet’s use of language. Listen to this:

She watches—impatient—

for quick spark of flint, for slight sliver of ice,

for rough calving, and then lightning birth.

She waits for crashing of form fashioned into another—

mirrored mosaic on cobalt water. (14)

The alliteration, the assonance, shiver on your tongue.

The poet’s use of metaphor also compels. There is a constant tension in the elements, including tension of perspective. For example, light is a guide but also leads through fire:

Light a match, a candle, a torch that will guide…

….

She puts her palm up, open, and presses it to the glass so that

fingerprints find homes in molecules that refuse to dance…

….

…the motion of a lake that feels like an ocean when mid-life

swims out ahead and doesn’t wait for the other swimmer

…her compass isn’t clear (17)

At times I felt lost, or swimming in the liminal space that Fahner creates, or unsure of who I was with, but that seems the point, and the imagery carries me along. The poet takes readers to Ireland, to Northern Ontario (she even finds beauty/interest in the tailings ponds), to the Maritimes; we are treated to fiddleheads, oysters, birds on stilts, lakes, oceans and icebergs. There are “seal women” in the background “hiding behind / black rocks, hair woven / with seaweed, skins / in their cold hands, pale /fragile.” (20) The selkies are the constant in the “unsettled spaces.” (16) Even these double entendres of the unsettled work poetically to guide readers through a mythical but very real journey when mid-life swims out ahead. Again and again, the vibrant imagery creates tension, a tension of love and longing and readers are there, watching, “a life mapped by strange frame, / cars stopping in the road outside” (69), and we are left swirling in the wind of it all. And searching for home. But home seems more a journey than a place, an unsettling.

Then there are Fahner’s images of rebirth, very much a constant in this book, and because we already know that everything is not as it seems, that perspectives shift, “reborn” (21) doesn’t necessarily mean a positive ending. Nor is it negative. There are tempests, and the narrator guides the reader through swells of waves and the rejuvenating storms, fire and water, and air. In “Reminders” (51), the narrator asks for vulnerability:

I wish to be a planet, turn slowly and see

night become day over and over again

to feel that throb of rhythm,

heartbeat where the skin is thinnest,

at my wrist. Kiss me there (51)

The poet reminds the reader that the journey is all about the journey, not the end, but vulnerability, the swells, the anticipation, not the destination, but the “fireflies and dragonflies / luna moths and honeybees / pebbles in pockets to fashion paths.” (84) While we might already know this, we see it and feel it anew from the poet’s eyes.

I am magic—making myself over and over again

until the planet stops turning, the branch

stops reaching, the fish stops swimming. (51)

As readers, we are with her, mesmerized, searching, anticipating, Emptying the Ocean, “carefully, one bucket and then another—a pint of ocean at a time.” (25)

Beth Everest enjoys the freedom to write, to create jewelry, and to dig carrots in her own garden. She is fortunate to publish in journals across the country, and occasionally come out with a book.