by Ed Hamer

by Ed Hamer

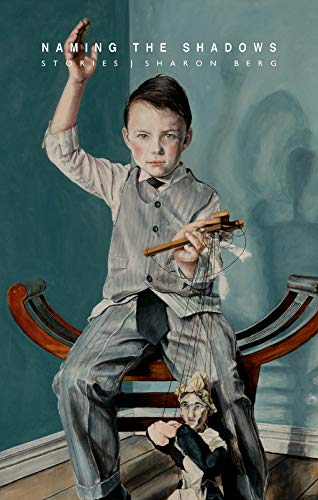

Naming the Shadows

by Sharon Berg

The Porcupine’s Quill (2019)

ISBN 9780889848665

The Stories Themselves:

Sharon Berg has written a collection of short stories, really a powerful gallery of highly visual tales that evoke our desire to look into them intensely and to see deeply. Inside the tableaux, she plants the ephemera of psychic shadows and these are certainly enough to launch strong flights of our imagination. So we are reading and interpreting at two quite different levels.

And she holds true to her initial quotation from Jung:

one does not become enlightened

by imagining figures of light

but by making the darkness conscious

These stories are laden with darkness and it transforms the reading of the apparent into a reading of the obscure and difficult. Like visual art at its best Berg avoids prettiness and too easy legibility. Again, as with difficult visual art, Berg works to make the ritual of reading transformative — calling on us to develop solutionary insights into very difficult situations and very difficult people.

Some of the Stories…

The first story in the collection, “A Violet Light,” ‘Before the Mirror, Édouard Manet, 1876’ makes reference to this painting by Edouard Manet of his wife, Suzanne, the principle of the story, whom he painted, in younger happier times from behind, as she undressed, with her bare, pale shoulders. Of course, he had already made a name for himself with the nude odalisque “Olympia,’ so his work was certainly admired for its risqué quality. The picture of his wife is of a muted sensuality.

But the title of the story, “A Violet Light” recounts the arrival home of Manet after a long absence and a long painting dalliance with Berthe Morisot, certainly a demoiselle élue in artistic circles, herself a painter, and soon to be married to Manet’s brother Eugene.

The painting he brings home in the story is of Morisot with violets, and the same violets he brings home for his wife. Inside the intrigue, we see evolving the details of Manet’s shadowy relationship with Suzanne. It is Suzanne who endures the emotional schisms with Manet, and it is Suzanne who preserves a perfect bourgeois tableau of the couple so Édouard will not suffer the scandal of a too dangerous liaison and will be able to keep up appearances and proprieties.

Quite ironically the real creative work in their relationship, the managing of the dissonances, and difficulties, for this socially achieved couple falls upon Suzanne.

But Berg has no apprehensions about dealing deeply with other class levels, with other formations and scripts. “Trespass” is about an encounter between two farm children — a brother and a sister — in rural Canada and quite vicious and unregulated neighbors who pummel into them at a culvert-fort and inexplicably beat and bloody them. The farm kids have no defense when the fight escalates to the demand that the sister expose herself, so the brother resorts to a hysterical laugh-scream that fortunately terrifies the small gang. They leave and a deeply disquieting and muted peace is restored. But we have seen into some real human malice—in a rural setting—and happening all the while their father, unaware, ploughed and turned the soil.

Quite contrastive, but also fraught with shadows is “A Different Sort Of Wealth” –a novelette — set in another rural setting — dairy country in Prince Edward County, that peninsula that pushes its gentle beaches into Lake Ontario, and is highly fertile.

It starts off with delicious ambiguity. An old man is whistling his girls through a grey, drizzly morning, but it’s eventually all about milking, and getting his girls into the barn and the milking machines. His son — solitary, reclusive, and single but quite cheerful is the one primarily responsible for running the farm. Full of jokes and lightness he manages to hide an unspoken sadness about the wife he never found.

But things change somewhat. The dairy farm across the road is sold and in moves a family with children. With children across the road his life changes. He can teach them everything about the cows’ bovine mysteries, their strength, their gallonage, their characters, and specificities. But essential is that humans keep their distance and not get too familiar.

So in a situation where we could have feared too much human familiarity and contact [more shadows?] the ruinous familiarity is between the children and the calves. The calves learn to love their closeness to the children, and when they are no longer calves, wanting more closeness, jostle Harry, and do major rib-crushing damage in a milking stall.

So the truth will out — secretive visits to the calves, too much familiarity with humans, and the children are eventually moved from their Prince Edward County farm. But there is a wonderful residue to the story (those tasty bits like the curds the children eat at the cheese factory!) These are all the fine feelings Harry felt for the children. This time the yield of the shadows — the misplaced, the too deep familiarity of the children, chucking the calves, is nutritious.

Another story about young people, this time young girls, is “Out of the Blue.” Four girls consider themselves to be a quartet of singers and have lots of aspirations about eventually performing. They decide to try to mitigate the oppressions of shopping with their Moms for school clothes, and go together on their bikes to the mall. They are sure they can do a better job.

The shadows in this story emerge when they discover a long, shiny aluminum Airstream trailer at the mall, unexpectedly housing a couple of midgets, who have put themselves on public view. The girls pay and go in, and are overwhelmed by the apparent humiliation this very staid, very correct and made-up midget couple have brought upon themselves. The quartet has seen too much and leaves in psychic disarray. One girl needs to return to apologize for looking, but the feeling in the story is they are all chastened by this humiliating display in such a public context.

“Jigsaw Puzzle” is short, developmental story, a Bildungsroman of a young woman with parents who were struggling to learn the craft of artist well before she was born, with a lot of serious study and attempts to emulate the greats, all the while in a relationship fraught with difficult emotion.

An essential element of the story is the attempt of their daughter, Nia to garner details about the kind of man her father was. She learns he was a tall man, red-haired, quite physically taxed, many accidents, his bones full of pins, a broken nose, muscle transplants from his gluteus — essentially someone who never wanted to be a father. But he was passionate about art and taken to pursuing painting in high school. It was painting that became the basis of this couple’s relationship.

Into this difficult household with two parents abused over their own upbringing, Nia tries to compose herself and initially fails. So she attempts to commit suicide. That doesn’t work either and she leaves home for downtown Toronto and seamy inner city hotels.

Inside the defiance, even the reader might feel for the confusion and plethora of accidental events and details, another shadow miraculously emerges. Nia, careening towards a dissolute and self-destructive life arrives at her mother’s house and mirabile dictu presents her with a proposal — a list of chores she will undertake and a self-imposed curfew, signaling her willingness to return.

So she moves back and in the protracted dialogue with her mother, she learns the details of the father she never had, this man who never really wanted to be a father.

But in this mother-daughter dialogue, something else emerges. Each begins to put together a clearer picture of her own portraiture. In fact, the creative, artistic instinct in both surges forth to affirm an ever-clearer picture of who each is.

Then the story moves to a very rich coda. It is filled with the affirmation of how it is possible out of disorder and chaos to compose a life, but equally, how two women mother and daughter can be Both beautiful and creative. Both are able to “jigsaw it together.”

In “The Secret” we are in an entirely different quadrant of story-telling, beyond the suffering inside the chaos. It depicts the life of a professional woman, a doctor of psychiatry, but one who is a princess of revanchisme. It’s about how in her acts of love she recovers the power and control she lost as a twelve-year-old girl.

She is an eminently attractive and an eminently rehearsed adult, blond, a petite perfection, able to script for herself perfect amorous encounters. She beds men and offers them deliciously exhausting satiety, and then pleads for more.

But here the writer’s shadow-creation is especially formidable. The psychiatrist’s motivation for these perfected love scenes is control, and her ritual is precise. She collects trophies. The discarded condoms she washes and assembles in her closet in a Calder like mobile. Stray pubic hairs she sleuths, collects, and notes with all the amorous and physical details including size and circumference — all with the goal of “distancing herself from the memories of a twelve-year-old girl who did not know how to resist the attention of men.” Clearly, we wonder whether this is a shadow diminished by these attempts.

Beyond the Pretty, and Visually Attractive, & Into the Province of Difficult Writing:

Of course one of the most interesting aspects to be learned from visual art — impressionist unto stylized and abstract — is that the best work is generally not the most attractive but rather the most difficult. We are drawn to difficult looking and it engages us. And it is this engagement that stimulates our imagination and requires that we make sense of it.

In Naming the Shadows we have something similar. Despite being highly visual there are no tableaux in the book we can call attractive, although the bourgeois household in the Manet story has an uneasily achieved order and tranquility. Maybe we can imagine the dairy cows in “A Different Sort of Wealth” as offering their gallonage along with contentedness. Even the long glistening Airstream where the midgets show themselves has an attractiveness.

Still, even in these attractive scenes quite probably a contrastive intent is at work; the shadows are peopled by difficult versions of humanness, all are works in progress, souls dealing with difficult lives. So naturally, we are engaged by these characters and want to bring our rationality and affect to bear, to think why they are the way they are, and how they will eventually compose themselves, and recover, find their tranquility. Problematic lives really constitute something akin to difficult looking and we are only able to resolve the anguish these characters present us with through some analysis and tactical solutionary thinking.

And What Is a Ritual, After All?

Looking at difficult visual art has been called a ritual (we have only to think of Kandinsky or our own Lawren Harris). Walter Benjamin in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936) laments how art had become commercialized, prettified, and made irrelevant. He contends that real art, difficult art that requires deciphering and making sense of is, in truth, a ritual. We can surmise something similar happens with writing.

Maybe the literature on the difference between games and rituals (Levi-Strauss, Savage Minds) is useful here. He suggests games produce winners and losers, but rituals allow everyone to pass to the winning side. No doubt this difference applies to both visual art and literature — the too beautiful in each case leaving us in an admiring suspension of disbelief and astonishment.

And the difficult, the edgy, the problematic in each case?

We are obliged to make sense of the disquiet each produces, and the solutions we generate in that work itself, and eventually in our own lives allows us all to pass to the winning side. The artist foments our internal creative discoveries, and about ourselves.

This is Sharon Berg’s work. She has certainly eschewed the unduly attractive. And in her work, in order to present the shadows of our humanness that we have to capture sight of, and then make sense of, she offers us a ritual.

Without question a careful read allows her stories to be transformative. These stories will change us.